Wide Shot: ‘Black Widow,’ Hollywood’s next megadeal and more big midyear questions

Six months ago, we launched the Wide Shot newsletter with a few big questions for Hollywood — and some light predictions — for 2021 as the industry was in the midst of earthshaking changes. If you haven’t signed up to get our coverage in your inbox, please do so here.

With the inaugural edition in January, we tried to foreshadow the fate of the movie business, the trajectory of the streaming wars and the intentions of the new Biden administration toward tech deals. It’s only fair that we revisit those queries at the half-year mark.

So how’ve we done?

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Well, a lot has happened already in 2021. A tech company finally bought a movie studio. AT&T, after turning the film industry upside down, decided to cut and run. The group behind the Golden Globes descended into utter chaos. Everyone from Reddit traders to Vin Diesel took credit for helping save the movies.

As I was preparing this blast, titans of industry (Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, the Bobs Iger and Chapek of Disney and Andy Jassy of Amazon) were descending on Sun Valley, Idaho, to enjoy the billionaires’ “summer camp” and shape the future of media, tech and entertainment. Future Oscar contenders began screening at Cannes, reviving the French festival’s feud with Netflix. And Disney launched the first theatrical Marvel movie in two years.

It’s almost as if we planned it that way.

Wide Shot midyear progress report

Are movies dead?

On the one hand, “Black Widow’s” $80-million domestic opening weekend was the latest sign of recovery for the box office, building on the momentum of “Godzilla vs. Kong,” “A Quiet Place Part II” and “F9: The Fast Saga.” The U.S.-Canada sales were right in the middle of the expected range of $70 million to $90 million.

But everyone was soon talking about the other big number: $60 million in global sales from the film’s release on Disney+, which charged people $30 to watch the blockbuster at home. This was notable because 1) that’s a lot of money and 2) it’s the first time one of the big studios has publicly disclosed sales data for a simultaneous premium video on-demand release of a major Hollywood film alongside its box office tally.

What does it mean for the future of how we watch movies? Certainly, the at-home release ate into some of the weekend box office, though Disney keeps much more of the revenue from Disney+ Premier Access than it does from theaters. It doesn’t look like there was enough cannibalization to stop the company from doing similar releases in the future. Disney may not continue to release its biggest franchises on Disney+ simultaneously with theaters, but for other movies like “Jungle Cruise,” why wouldn’t it?

Coincidentally, the release came just days after media mogul and former Paramount and Fox boss Barry Diller, in an interview with NPR from Sun Valley, declared that “the movie business is over.” He blames streaming services and algorithms for a lack of quality films and the absence of money and energy around the buildup to major releases. It wasn’t a surprising sentiment coming from Diller, who hasn’t run a film studio in decades.

And yes, the movie business has changed radically, with studios using films to pump up their streaming services and placing much less emphasis on the multiplex. The “big screen is back” rallying cry offered by the theater supporters is probably a tad premature. As Mark Olsen and I wrote this week, indie films and art-house theaters are still struggling to make their comeback.

Even if same-day releases go away, theatrical windows have been cut in half from 90 days to a consensus of about 45. That’s good for consumers who want to choose how they watch films. It’s not great for theater owners. But people were always going to head back to theaters when the films they wanted to see were available. Recent releases represent positive signs for when “Top Gun: Maverick” and “No Time to Die” finally arrive.

Streaming services that were once almost solely obsessed with TV series are now heavily investing in films because, as it turns out, people like watching them no matter where they play. The experience of seeing movies will be very different than it was even in late 2019. But it hasn’t died.

Deal time!

Our inaugural edition asked, “Who will buy a studio?” Boy, did we get answers. One was a surprise, with Discovery’s $43-billion deal to create a new company with WarnerMedia, ending AT&T’s ownership of Warner Bros., CNN and HBO. The other was kind of expected. Amazon is paying $8.45 billion to take over “Rocky” studio MGM.

The big unknown now is what deals come next? Wall Street loves the idea of Comcast combining NBCUniversal with ViacomCBS to create a super streaming service that could legitimately compete with Netflix and Disney+. Comcast Chief Executive Brian Roberts doesn’t think the company needs to do a deal, according to the Wall Street Journal. Still, the cable company did consider bidding for the WarnerMedia assets, so there seems to be an appetite.

Meanwhile, Discovery Chief Executive David Zaslav told CNBC from Sun Valley that he’s not done making deals yet, in that vague but intriguing way that executives speak at conferences.

What other combos are left to make? For starters, studios like Lionsgate, Sony and Legendary remain potential targets for anyone with deep enough pockets. Streaming device seller Roku could be an interesting play for a company wanting to control more distribution. The combined Warner Bros. Discovery could be a compelling acquisition target down the road. And Apple, which has been dipping its toe in entertainment, still has a massive cash hoard.

But the bigger the deals get, the more serious the regulatory hurdles become.

New antitrust universe

Merging NBCUniversal and ViacomCBS would almost certainly raise regulators’ eyebrows, because it would result in one owner for two broadcast networks. But as a friend of the Shot recently asked me, “Why would anyone care about broadcast nets in a world where Amazon is buying one of Hollywood’s oldest studios?”

In January, we asked, “Will Washington hobble Big Tech?” It’s sure trying. After Amazon announced its MGM deal, some entertainment industry lawyers argued that the government would be hard-pressed to argue that buying the tiny studio would give Amazon monopoly power. That may be true, but it looks increasingly likely that the federal government will try anyway.

The deal is being reviewed by the Federal Trade Commission, led by noted Amazon critic Lina Khan. Amazon wants Khan recused. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) wants the FTC to go hard on founder Jeff Bezos, et al., as Amazon “accelerates its aggressive monopolistic behavior.” As AT&T knows, the government doesn’t have to win its antitrust cases to cause headaches that linger for years.

President Biden’s newly signed executive action to rein in big business will improve competition and save jobs, supporters say. The political environment has changed, with both major parties arguing for methods to constrain tech companies in nontraditional ways. Vertical deals (companies buying their way into other areas of business) were once seen as safer than horizontal deals (combinations of firms in the same industry). Not anymore.

New fronts in the streaming wars

It’s still not clear how HBO Max and discovery+ will work together when they’re under the same corporate roof, but the deal could presage a great rebundling of services into a facsimile of cable online.

Who’s winning in streaming? MoffettNathanson, an independent research company, last week released a fascinating report, using data from analytics firm Antenna, to assess which streaming services are making the most money per user after adjusting for promotional pricing and giveaways and which have acquired the most market share.

For some, it’s slow going. Peacock has only 3 million paying domestic users a year after launching, according to MoffettNathanson estimates. Paramount+, formerly CBS All Access, has an estimated 10.4 million. One takeaway is that Disney+ has been able to grow quickly thanks to its strong consumer brand and the quality of its service and shows. Rivals have had a harder time on those fronts.

But while Disney+ has big subscriber numbers, it clocks in with a low revenue per user (RPU, pronounced “arr-poo”) figure, because of its low price and use of promotional partnerships and third-party distributors. Disney+’s estimated effective RPU is $6.32, according to MoffettNathanson, compared to $7.05 for Peacock, $12.19 for HBO Max and $14.88 for Netflix. Analysts broadly expect Disney to continue raising prices as it expands its market share. Disney-controlled Hulu, an early mover in the space, has high RPU and market share.

Netflix and Disney+, the leaders in the streaming race, both saw their growth slow in their most recent quarters, after big surges at the beginning of the pandemic. It’s not clear whether the slowdowns are just momentary blips because of the acceleration in signups caused by the pandemic, or if they’re a sign a of bigger challenges.

Will Hollywood’s culture change?

The troubles facing the Hollywood Foreign Press Assn., the group responsible for the Golden Globes, are in some ways emblematic of the challenges of changing the industry more broadly.

Placated for years by the studios, the HFPA has been criticized for its culture of “self-dealing,” “corruption” and “insulation,” in the words of its own departing members, months after an L.A. Times exposé renewed focus on the organization earlier this year. The two members who revolted last month attacked promised reforms as “window dressing.”

The revelation of the HFPA’s total lack of Black members collided with an industrywide reckoning on race and inclusion. After the killing of George Floyd, appeals to racial justice and promises to overhaul Hollywood’s culture emanated from the studios and media companies. What has resulted from those statements, and whether or not they’ve had meaningful effect, is a subject that deserves its own edition of this newsletter.

Among other things, the industry still has serious issues with bullies, toxic workplaces and its talent pipeline. I recommend reading and thinking about this commentary by Times deputy sports editor Iliana Limón Romero on ESPN’s recent problems keeping top Black talent.

Notably, outside the studio system, grass-roots organizations stepped up their own initiatives to diversify film sets, including #Startwith8Hollywood, a program launched last year by women of color, and Array Crew, set up by members of Ava DuVernay’s nonprofit Array Alliance.

Stuff we (and others) wrote

— The latest in our Explaining Hollywood series: How to get a job as a film editor. (LAT) Have big Hollywood dreams? Get caught up with the L.A. Times guide to entertainment industry careers.

— How Aryeh Bourkoff became media’s hottest dealmaker. Even if you don’t know his name, you’re familiar with the megadeals the LionTree investment banker has helped engineer. (THR)

— “Black in Mayberry.” Meg James’ great read on how a film exposed racial tensions in El Segundo, one of L.A. County’s whitest cities. (LAT)

— Can a Barbie movie work in the 21st century? (NYT)

— Reese Witherspoon’s media company, Hello Sunshine, is exploring a sale. The company behind “Big Little Lies” and “The Morning Show” has received interest from suitors including Apple. (WSJ)

— Tim Robinson is sorry for yelling. On “I Think You Should Leave,” the comedian’s anxieties fuel a vast world of jerks, idiots and outright a—holes. (Vulture)

— Justin Ray: Past coverage failed the transgender community. It’s important to recognize it. (LAT)

Number of the week

Under a normal film output deal, a studio puts a movie out in theaters, and after its run in multiplexes and on home video, it heads to a pay-TV network (say HBO). HBO gets the exclusive license for an 18-month “Pay One window.” The deals are typically worth more than $200 million a year. It’s a good business that hasn’t changed much until recently.

NBCUniversal last week became the latest studio to upend that. Streamer Peacock will get the films “no later than” four months after they debut in theaters, starting next year. It will presumably boost signups for the paid version of Peacock, because people who use the free version won’t get the movies.

Here’s where it gets weird. Peacock gets the Universal movies for the first four months of the 18-month window. After that, another streamer (Amazon, for live action movies) gets the licenses for the next 10 months. After that, the movies revert to Peacock for the remaining four months. Animated movies, which have their Pay One arrangement with Netflix, will go to a streamer other than Amazon for the middle 10 months. Whew!

The reason for this complex arrangement partly boils down to Comcast’s half-in, half-out stance on streaming. The company wants growth at Peacock. But it also doesn’t want to sacrifice the licensing revenues it gets from third parties.

Hollywood production

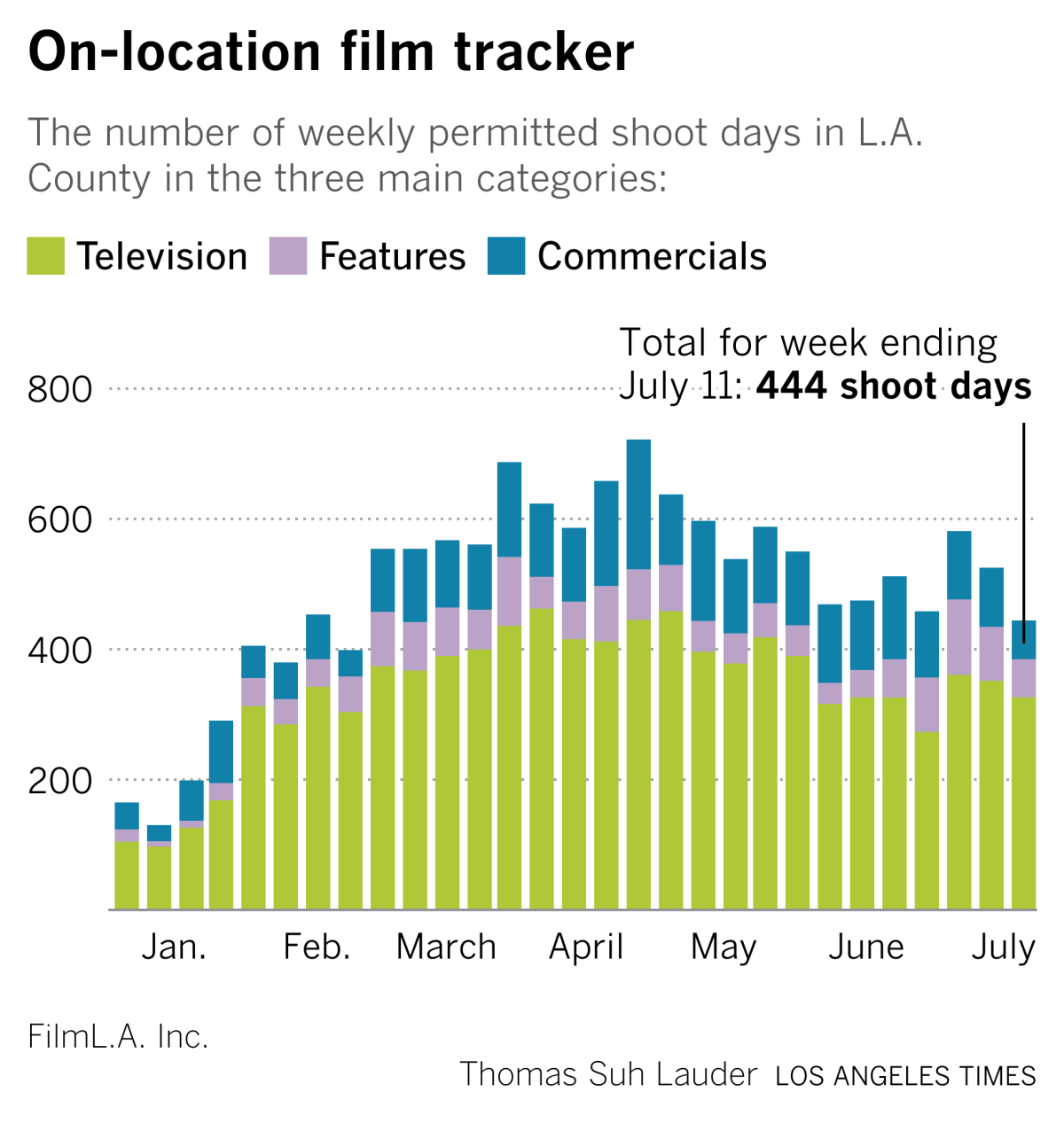

The Wide Shot on-location production tracker is back after last week’s holiday. Shooting in the Los Angeles area declined to 444 days during the week that ended July 11. We’ll be back soon with year-over-year comparisons.

Final shot...

“Blue Weekend,” the latest album by the London alt-rock band Wolf Alice, makes the most of Ellie Rowsell’s powerful vocals on songs like “How Can I Make It OK?” and “Smile.”

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.