On the Shelf

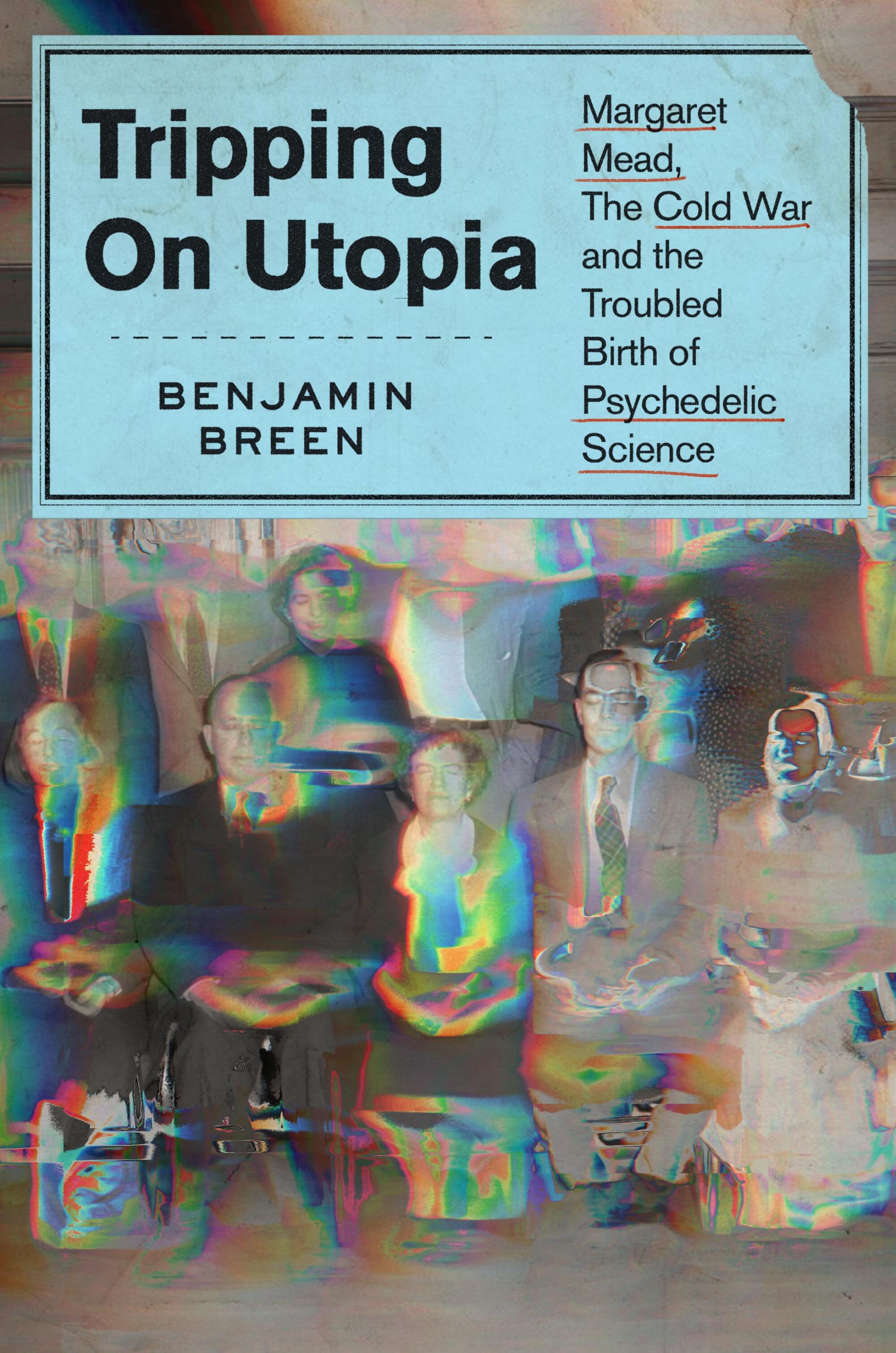

Tripping on Utopia: Margaret Mead, the Cold War, and the Troubled Birth of Psychedelic Science

By Benjamin Breen

Grand Central: 384 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

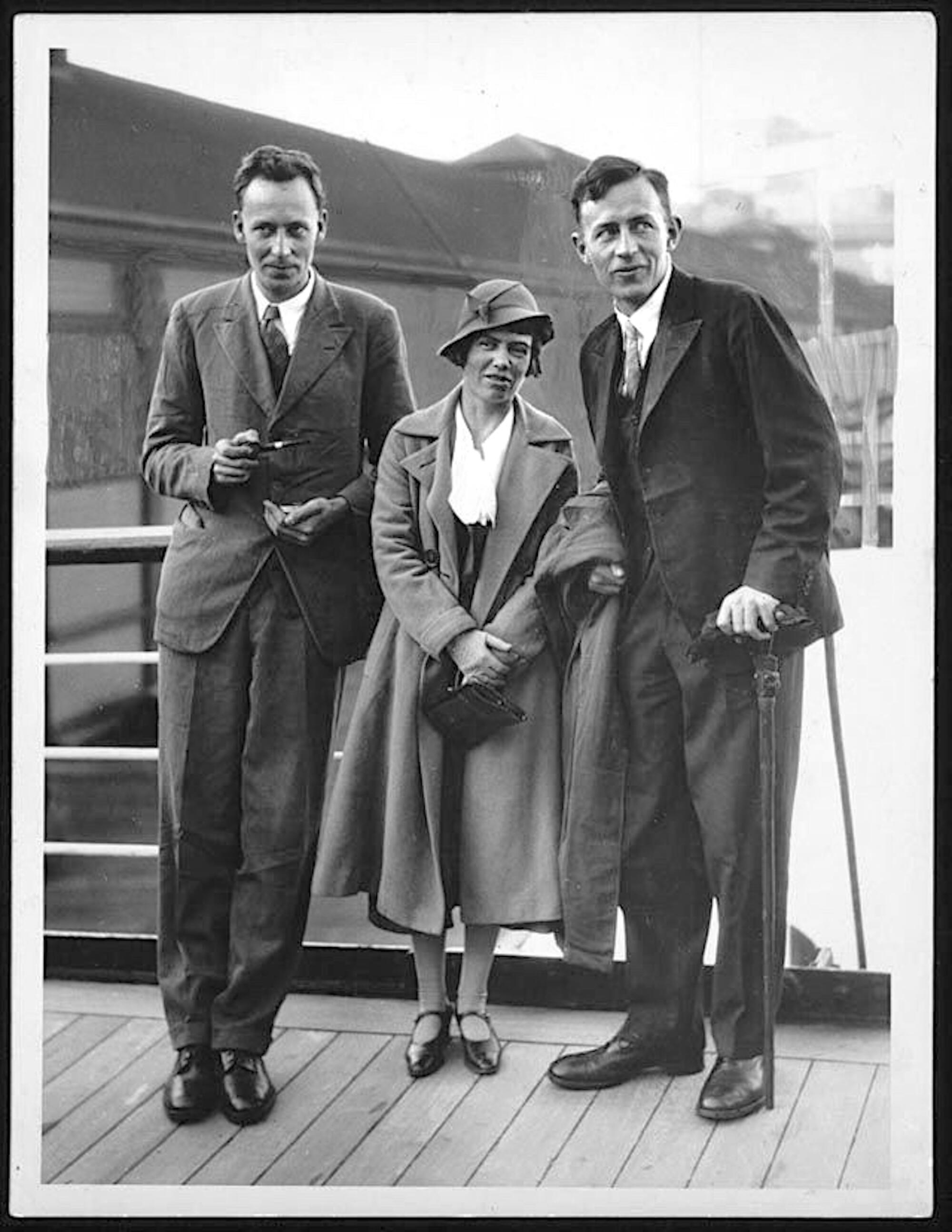

Benjamin Breen, a young historian at UC Santa Cruz, has written a gripping new book that tells a remarkable story. “Tripping on Utopia: Margaret Mead, the Cold War, and the Troubled Birth of Psychedelic Science” tracks the souring of the idealism once associated with the study of psychedelic drugs in the 20th century. More concretely, it focuses on the intertwined lives of two cultural anthropologists — Mead and Gregory Bateson, who were married for 14 years — and the extraordinary circle of social scientists, psychoanalysts, artists and spies who gathered around them from the 1930s through the ’70s.

Incorporating fresh archival research into his comprehensive history, Breen manages to show how these drugs went from being seen as a possible panacea to a proposed weapon of war to a countercultural plaything — and how, in tandem, the utopian dreams of science and counterculture alike gave way to the end of American optimism.

Having myself written a biography of Bateson about 40 years ago, I approached Breen’s book with a naive confidence that there wasn’t much left for me to learn — that, having met many of its principal characters, I had understood Mead and her cohort in all their flawed promise. In fact, I came away with both wonder at what Breen had unearthed and a twinge of envy that I had missed so much of Bateson’s life in particular, hidden away at the time in archives at UC Santa Cruz that have since been unsealed.

I spoke with Breen last month to find out more on how he managed to complete the picture, and to ask whether current studies and medical uses of psychedelics are bringing us full circle. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

In “The Last Man Takes LSD,” two authors track Foucault’s late-in-life rightward turn, beginning with a hallucinogenic 1975 visit to Death Valley.

How did you get started on this project?

I’ve been interested in psychedelics for years, and they show up in my first book, where I looked at the 17th century European encounter with psychedelics like ayahuasca and peyote. So it was on my radar. But the real reason that I got into this particular story was coming to Santa Cruz and reading through Gregory Bateson’s archive, which I just thought was amazing. Then, I went to the Library of Congress to look at Margaret Mead’s papers, and I found a folder called the “LSD Memo” from 1954, and that had all of her field notes where she was thinking through a new research project about LSD. It connected a lot of dots for me.

Did you interview sources as well?

There were a couple people who survived. One was actually a secretary at the office where Mead was helping with LSD research in 1954, and I was able to track her down just by figuring out information about her in Mead’s notes in that LSD Memo. She was in her 90s. and she added all this detail about being a participant, a volunteer guinea pig basically, in a psychedelic study in the mid-’50s.

Could you summarize the trajectory of psychedelic drugs?

I think one of the main things to get across is that psychedelics have a very, very old history. So a lot of the ways we’re talking today about the resurgence of psychedelic therapy, [that] begins at the actual end of the story — thousands of years of history of humans using psychedelics, including for medicinal and therapeutic reasons. But there’s a key moment in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when cultural anthropologists focus in on aspects of consciousness alteration among Native Americans.

Specifically, in the aftermath of World War I, they wonder: How can we reshape human society and ways of thinking? To move away from feedback loops of self-destruction and violence. In the interwar period, it becomes utopian and very deeply ambitious and a form of science. People in the ’20s and ’30s genuinely thought science could, for instance, lead to the formation of a world government.

What were Mead’s and Bateson’s roles in this story?

Mead and Bateson thought that scientists would lead the vanguard of a revolution in bringing the wisdom and the experiences of other cultures into the modern world, the creation of a sort of global culture that would allow for some form of transcendence. World War II really changed their view.

We’re taking a closer look at how ketamine is being used to treat depression, the path the drug took from general anesthetic to taboo rave drug to an off-label psychiatric medication, and the potential pitfalls.

I’m interested in the weaponization of psychedelics for military intelligence in the postwar years.

So there was a strong belief that in the aftermath of the atomic bomb that the way to win a war was to never end up in actual combat. Psychological warfare was the way to go — you know, basically the idea of game theory. For instance, the American side imagined, “What if the Soviets have a mind-altering drug and they give it to the president of the United States or slip it into the ambassador to Moscow’s drink?” That concern actually prompted parallel work by the CIA and the U.S. military. Drug and chemical warfare was sort of a parallel arms race alongside the nuclear arms race.

And that is what we mostly associate today with MKUltra. But it was much bigger than that. There were many other programs. and I barely scratched the surface. For instance, the idea of dropping aerosolized LSD over cities was something people thought about, but also [to use it] as a tool of diplomacy, a way of interrogating suspected double agents, even as a way of inuring Americans in the State Department. There were many layers of paranoia.

As you reveal, both Mead and Bateson were involved to a certain extent with American spies. How would you describe their interaction with espionage?

Extremely complicated. From what I can tell, [Mead] was a true believer. She believed that all the work she was doing was a good thing for the world. At the same time, the view I have is that she likely knew psychedelic research was funded by the CIA. Bateson’s a little bit harder to get a sense of. He was clearly involved in intelligence work in the early ’40s because he was in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). He was strongly disapproving of Mead’s government work in the ’50s. He ended up being an outspoken opponent of psychological warfare after World War II.

An outstanding moment in the book, at least from my point of view, occurs when Bateson writes [OSS director William] Donovan in the aftermath of Hiroshima advocating for the establishment of a new and independent intelligence institution. What kind of impact did his advocacy have on the origin of the CIA?

You know, he was saying, indirect methods of warfare will trump direct warfare, and that was what the Cold War was about. He was right. It was very precocious. The way I found out about it was actually in an internal CIA history written by Arthur Darling in the early 1950s. It’s hard to know Donovan’s perspective on this, but we know that it was important because it’s right there in the official CIA history of its own formation.

Scientist, who died at 80, oversaw invention of devices for assassination and gave ‘acid’ to human guinea pigs.

If, as your book argues, when psychedelics came to play a role in hedonism and countercultural values in the ’60s and ’70s, this was the end of an era rather than a new beginning — how does that illuminate our current era of psychopharmacology?

There’s some truth to the idea that we’re coming full circle and returning to the type of approach that was prevalent in the ’30s and ’40s. What I mean is that thanks in large part to Margaret Mead’s vision of science as something which can help everyone in the world, psychedelics were initially thought of as a tool that could be very broad-based. So it would not be limited to one subculture, one social group, one nationality, one gender. So the trajectory I see limited the scope of psychedelic science in the ’60s.

And one of the people who, I think, was a really interesting figure in that story — [Beat poet] Allen Ginsberg used psychedelics in the ’50s [and had] this extremely expansive view of what they can do initially that tied in with his religious beliefs. He was friendly with Bateson, and he and Mead made a radio show about the Beat Generation. But when Ginsberg fell in with the counterculture, it became “turn on, tune in, drop out,” meaning a rejection of the world — which is antithetical to how Mead thought.

When Bateson set him up with an LSD study being conducted in Palo Alto in 1959, which was the first time Ginsberg used LSD, he wrote to his father, Louis Ginsberg: “You should try it too.” But then in the mid-’60s at the Dialectics of Liberation conference, which Bateson also spoke at, Ginsberg says there’s no shared culture. I think that limited view of their role in society, for one thing, made it impossible for legal psychedelic research to continue to be conducted in Nixon’s America.

Now, I think that’s changing. I mean, psychedelics are no longer countercultural. Universities have psychedelics studies program. Berkeley has the Center for the Science of Psychedelics. It has returned to being mainstream and in some ways I see it as the fulfillment of what people were originally hoping for. So I’m very optimistic about that part of the story.

Lipset is a professor of anthropology at the University of Minnesota and the author of “Gregory Bateson: The Legacy of a Scientist,” among other books.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.