On the Shelf

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

By Malcolm Harris

Little, Brown: 720 pages, $36

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Malcolm Harris had the good luck to grow up in Palo Alto, a blessed piece of real estate in the American economy, lit by both the sun of Silicon Valley and the rosy sandstone glow of the Stanford University campus.

He also had the good luck to make it out alive. In the years Harris attended Palo Alto High, students killed themselves at a rate between four and five times the national average, walking to their deaths on the train tracks that Leland Stanford built to escape the labor unrest of San Francisco more than 100 years earlier.

Harris’ takeaway from the pressure cooker of Paly high was that fixing it required revolution, or something like it.

In high school, he was arrested on campus for handing out leaflets telling kids they didn’t have to take the state standardized test. He marched against the Iraq war and spun up a new chapter of Students for a Democratic Society when he got to college at the University of Maryland. There, he and his comrades began to occupy things — school buildings, oil company headquarters, political conventions.

By the time he got to the first meeting of Occupy Wall Street, in 2011, Harris had already started researching and writing about the precise ways in which the world is messed up, specifically in education and student debt. His first book, “Kids These Days,” tracked how millennials became millennials through the double ratchet of schooling and finance — forced to do more homework while the institutions assigning it kept raising tuition.

Even in his final act, the legendary scholar and theorist does not mince words. He sees an L.A. that is decaying from the bottom up.

But he knew he’d eventually turn back to his hometown to explain our modern world, now dominated by tech companies and their attendant billionaires. That one day he would come to write his latest book, out next week — “Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism and the World.”

We met on a winter day in Washington, D.C., to spend a cold afternoon wandering through the capital. Harris has lived on the East Coast since college (mostly in Philadelphia), but still carries himself with the Northern Californian combo of chill stoner vibes and a tightly wound core. He has a shock of red hair, like a cartoon version of a left-wing firebrand, but dresses like a man who’d rather disappear into a crowd. Ask a dumb question, as I often do, and he’ll nicely sidestep, then tell you what was wrong with your premise and recommend something to read.

He spent most of the last few years reading hundreds of pages for research, eight hours a day — sometimes on a park bench in Philly, more recently at a battleship of a desk in the National Gallery, where the office of the museum’s president has been turned into a deserted sitting room. His first iteration of the project was almost a memoir, but as he kept reading, he found more material that had been largely untouched — or at least unwoven into a sweeping history.

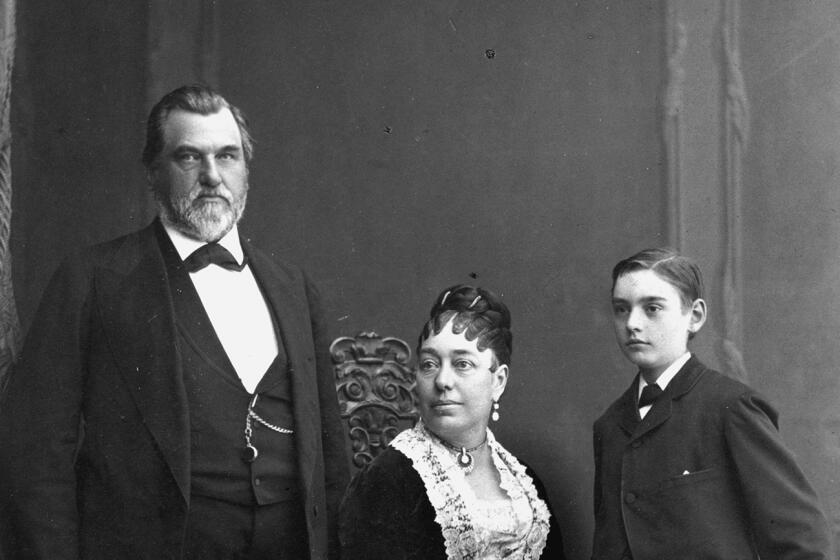

Like the story of the Palo Alto System: The railroad baron Stanford first used the land that would become his university as a horse farm, where he trained young steeds to the brink of physical collapse. Either the colt would break down early — and be shot — or it would survive the regime and live to progress the bloodline — and create more value for its eventual owners.

“When I’ve talked to my siblings and other people who grew up in Palo Alto” about the system, Harris said, “they find it chilling, the way they talked about young horses and early potential, and the way we saw kids in Palo Alto kill themselves because they didn’t measure up.”

Leland Stanford’s widow made many enemies. But who poisoned her? Stanford historian Richard White investigates in the new book ‘Who Killed Jane Stanford?’

“Palo Alto” follows the track from those early days to Silicon Valley now, tracing the way the eugenics of horseflesh and the frothy capital behind gold and railroads built an enduring machine that spits out scientific racism, hard-line anti-labor politics and high returns on investment no matter the human cost. It’s a sprawling tale, covering juicy stories like the probable assassination of Jane Stanford by the university’s first president; racialized labor wars; the campus’ midcentury communists; the university’s role in the Bay Area cocaine trade; and links between high-tech firms and international CIA plots.

Harris handles it all with dizzying detail and charmingly loopy metaphors — the recent vintage of tech moguls are described as both “slack-limbed puppets who have nailed their hands to these historical forces” and “Mickey Mouse [surfing] the wave in his stolen wizard hat, flashing a four-finger hang ten.” And that’s just one passage.

Harris describes himself as a communist, and that analysis is peppered through the text, but he has a knack for boiling down complicated dynamics to their blunt basics. “As workers have always been quick to understand, maximizing output tends to suck,” he writes early on; “if we see this process from labor’s point of view, it’s not the owners who generously split the proceeds of their investment with the workers, it’s the workers who split the proceeds of their extra output with the shareholders.”

Nevertheless, Harris set out to write a heavily footnoted history, not an anti-tech screed. “The book is not polemical. I’m a Marxist, I wrote a Marxist book because I think that’s the best way to get at the truth of this historical situation.”

The truth that Harris finds is wrapped around a few central characters, mostly big men on Stanford’s campus.

Herbert Hoover looms large as a graduate of Stanford’s first class in 1895, an international mine owner and manager and the core of a right-wing political cabal based at his eponymous institute on campus. Lewis Terman, the genetics-obsessed Stanford professor who popularized the IQ test, and his son Fred, who turned Stanford into a public-private powerhouse, follow suit. William Shockley, who invented the transistor and became a strident eugenicist in the 1970s and ‘80s, carries the ball another few decades. George Shultz runs it all the way to the 2000s, blessing Reagan and George W. Bush from the Hoover Institute throne. Meanwhile Stanford boys such as Dave Packard, Vinod Khosla and Peter Thiel kept investment flowing into the neighborhood with a dense web of companies spun out of Stanford research.

The president of Stanford University issued an apology this week for school policies that intentionally limited Jewish student admissions in the 1950s.

“I thought I was going to have to be more metaphorical” to connect those dots, Harris said, but the lines were already there: “Those horses were war instruments, as were the kids raised in Palo Alto for 100-plus years, according to the same concepts of efficiency.”

The playbook remains the same, whether it’s Stanford and Hoover or Thiel and Elon Musk on the field: Boost profits by squeezing labor and ignoring regulators; absorb massive capital and government investment; justify your success after the fact with pseudoscientific theories about your innate superiority.

But it’s not exactly the same as it ever was. Harris admits in “Palo Alto” that the story gets, in his words, “dumber” as time marches on. The technology gets less transformative, and the winners of the game seem to be randomly selected by venture-capital lottery. Investment firms such as Andreessen Horowitz have declared that “it’s time to build” real world-changing companies, only to pour billions into crypto-hype vaporware.

If you want to understand today’s Palo Alto, Harris said, watch “Shark Tank.” “It’s such a moment-by-moment feeling of how capitalists are vibing at that moment,” Harris said. “It was so fun during the pandemic — the first episode back, every one of them was completely foaming at the mouth, money was free. You’ve got a workout ball? Make it happen. And now they don’t care if someone has a perfectly logical business plan; if they don’t see it exploding they pass.”

So what is to be done? The book ends with a call for the official dissolution of Stanford University, at least in Palo Alto, and a return of the campus to the Indigenous people of the Bay Area. Harris sees it as a reasonable demand, considering the alternatives.

Indicted crypto billionaire Sam Bankman-Fried’s $250-million bail deal was the largest ever, secured with his parents’ house. But they aren’t typical homeowners.

“I don’t think that’s any less realistic than full employment; it’s not less realistic than Medicare For All, depending on your understanding of the situation,” Harris said. “So what’s the point of issuing that kind of transitional demand? It’s to delegitimize the sovereignty of the United States over the territory.”

Leland Stanford, grieving the death of his son in 1884, decided to found his university with the sentiment that “the children of California shall be our children.” Harris is simply taking him at his word: “Children of California? Well that’s me, so f— you.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.