‘Who Killed Jane Stanford?’ Solving the cold case of a California founder’s murder

On the Shelf

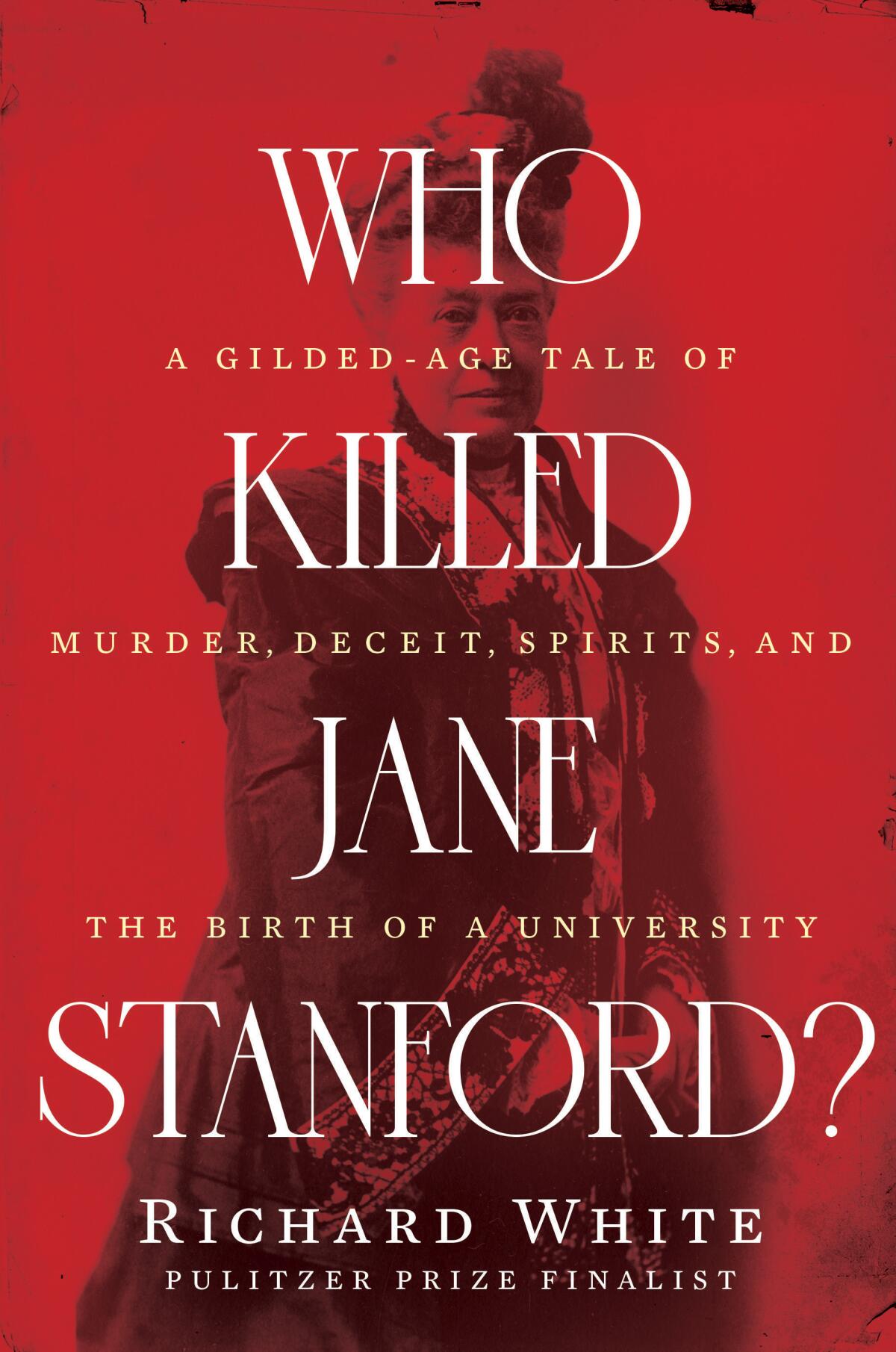

'Who Killed Jane Stanford?: A Gilded Age Tale of Murder, Deceit, Spirits and the Birth of a University'

By Richard White

Norton: 384 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Jane Stanford was a monstrous mess. The wife of railroad baron Leland Stanford, Jane was rich, duplicitous and convinced that God was whispering in her ear. Of friends and family, she demanded total devotion. Of adversaries, she expected evil opposition — and strategized accordingly.

None of this would have mattered to anyone other than the Stanfords’ relations, business partners, factotums and servants except for the fact that in 1885, Jane and Leland co-founded Stanford University, funding it with Leland’s ill-gotten gains. The gesture was a tribute to their only son, Leland Jr., who died of typhoid fever at age 15. After Leland Sr. died in 1893, Stanford University was Jane’s only love. She ran it like she owned it (which in fact she did). She nearly destroyed it with her whims and schemes until someone had enough and poisoned her — twice. The first round of strychnine, a massive dose of rat poison dissolved in a bottle of Poland Spring water, didn’t work. The second, pure strychnine slipped into a bottle of bicarbonate, did the trick.

Which of Jane Stanford’s many enemies tried to poison her? Which one finally succeeded in 1905, condemning her to a cruel death of excruciating spasms far from home in a Honolulu hotel?

It is this mystery that Stanford University emeritus professor Richard White tries to solve in his superb new book, “Who Killed Jane Stanford?” White brings the skills of an expert investigator to the task. He’s an acclaimed historian of the American West, and he knows the Stanfords’ deep history like the back of his hand — the corrupt influence of the railroads, the exploitation of immigrants, the criminals and grifters who ran early San Francisco. He taught courses on Jane’s murder at the university, drawing from the work of previous writers, notably Stanford surgeon Robert Cutler, who wrote a book undermining the university’s position that Jane died a natural death.

White writes with clarity, precision and a bone-dry sense of humor. He was aided by his brother Stephen White, an author of crime fiction, in shaping the narrative, and the book sustains momentum through plots, counterplots and diversions. Crucially, White has a lifetime of experience piecing together whole truths from a tattered and incomplete set of sources; some of the best bits in this story come from White observing himself trying to solve the puzzle. Here he considers one suspect’s memoir: “Memoirs convey the meaning of lives and the events that made them, but not necessarily what actually happened…. Bertha Berner lies in her book, but historians, like detectives, not only expect people to lie, they depend on it.… Lies are as revealing as the truth — they just disclose different things.”

Catherine Prendergast’s ‘The Gilded Edge’ retells a tragic early 20th century scandal involving Carmel Bohemians from the female victim’s perspective.

One of the biggest liars was Jane Stanford herself. She would savagely undercut a rival, and then, as strategic cover, she’d write an admiring letter praising her enemy to the skies. She ordered her servants around — admittedly what one does with servants, but she demanded total obedience. The servants lied in return as self-defense, about both their personal lives and the grift they had going on the side, raking off a percentage from the purchases of antiques they made on Jane’s behalf as her entourage drifted across the globe. Eventually they lied to investigators as well.

Jane hated socialists and the women students of Stanford with their wanton ways (by fin de siècle standards); meanwhile, she indulged herself as only a stratospherically wealthy person of the Gilded Age could. Jane Stanford is so very bad, she is good: When she finally died, two-thirds of the way through the book, I missed her.

There were many other liars, notably the president of Stanford University, David Starr Jordan. “Jordan epitomized pragmatism run amuck,” White writes, in a major understatement. At first Jordan’s lies were the byproducts of bureaucratic infighting, but eventually — fearful that a murder or suicide judgment would jeopardize Jane Stanford’s bequest to the university — he orchestrated a cover-up of her murder that even by today’s jaded standards was jaw-dropping in its preposterousness.

Finally, there were the police of San Francisco. In league with detectives hired by Jordan and other university higher-ups, they lied strategically and consistently, effectively discounting both attempts to murder Stanford by claiming she died of heart failure despite a Honolulu coroner’s jury verdict that she was poisoned. Just the crooked cops in this story would be fodder for a miniseries. Throw in Jane’s wacky spiritualism and lavish outfits, corporate corruption, academic animosities, warring newspapers and more suspects than you’d find in an Agatha Christie novel, and you have enough material for a full season.

Maud Newton’s “Ancestor Trouble” is more than a family memoir. It’s a journey through the thickets of Ancestry.com, genetics and white accountability.

There is even a fitting apocalyptic coda. Jane Stanford built a stone compound at the university as a memorial to her dead husband and son — a gigantic memorial arch, a church, a museum and a mausoleum where Jane would often pray and activate her divine pipeline to “guardian angels” Leland and Leland Jr. (“[God] takes my daily messages to my loved ones gone from earth life,” she wrote a friend. “He is like an operator at the telegraph taking dispatches from his children on earth to his children in Heaven.”) These monuments to adoration, vanity and delusion were heavily damaged in the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906. Many of the police records of the investigation, documents that might have revealed the truth of Stanford’s murder, vanished in the catastrophe.

Who killed her? White thinks he knows, and reveals his choice toward the end, but the journey to his conclusion is so absorbing it almost doesn’t matter. “Who Killed Jane Stanford?” shows that the fealty great wealth demands is an enduring cog in history’s gears. And the fact that Stanford University rose from this swamp of murder and conspiracy to become today’s renowned institution? That is perhaps the strangest plot twist of all.

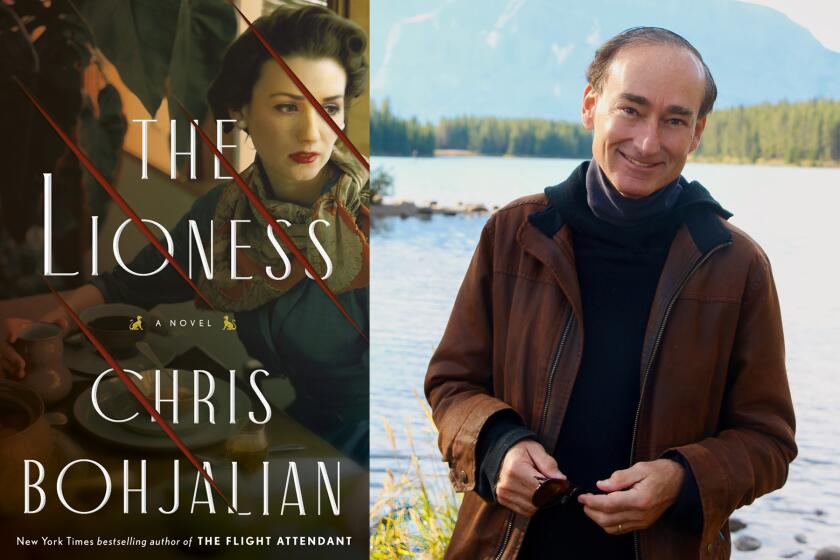

Chris Bohjalian’s latest novel, ‘The Lioness,’ features a 1960s Hollywood star’s honeymoon safari that turns into a thrilling psychological game.

Gwinn, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who lives in Seattle, writes about books and authors.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.