How a scholar unearthed the cyanide love triangle that toppled a California arts colony

On the Shelf

The Gilded Edge: Two Audacious Women and the Cyanide Love Triangle That Shook America

By Catherine Prendergast

Dutton: 352 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

One afternoon in 2014, the scholar Catherine Prendergast was rummaging through archives in UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library when she stumbled across a letter. “Motherhood! What an unspeakably huge thing for all my fluttering butterflies to drown in! A still pool, holding the sky,” the poet Nora May French had written. As Prendergast read on, the handwriting became shakier; French was in distress. She was writing to her lover, Henry Anderson Lafler, and relating to him — in real time — the effects of the drugstore-bought abortifacient that was now ending the pregnancy they had conceived together.

Such a firsthand account was extraordinarily rare at the time, but just as astonishing was its style. “She found me,” said Prendergast. “I felt like I knew her. You know, like these other women writers I hang out with who are just unspeakably clever, writing about their own lives and traumas and always turning it into something … her voice was extraordinary.”

Prendergast and I were speaking via Zoom last month about “The Gilded Edge,” her first publication for a general audience. Perhaps undiplomatically, I described the book, which came out this month, as “bonkers.” She couldn’t be more delighted. “As I said to my editor,” she told me, “my goal is for someone to say, ‘Holy crap.’” She called the process of writing it a “kinetic experience,” which she hopes is contagious.

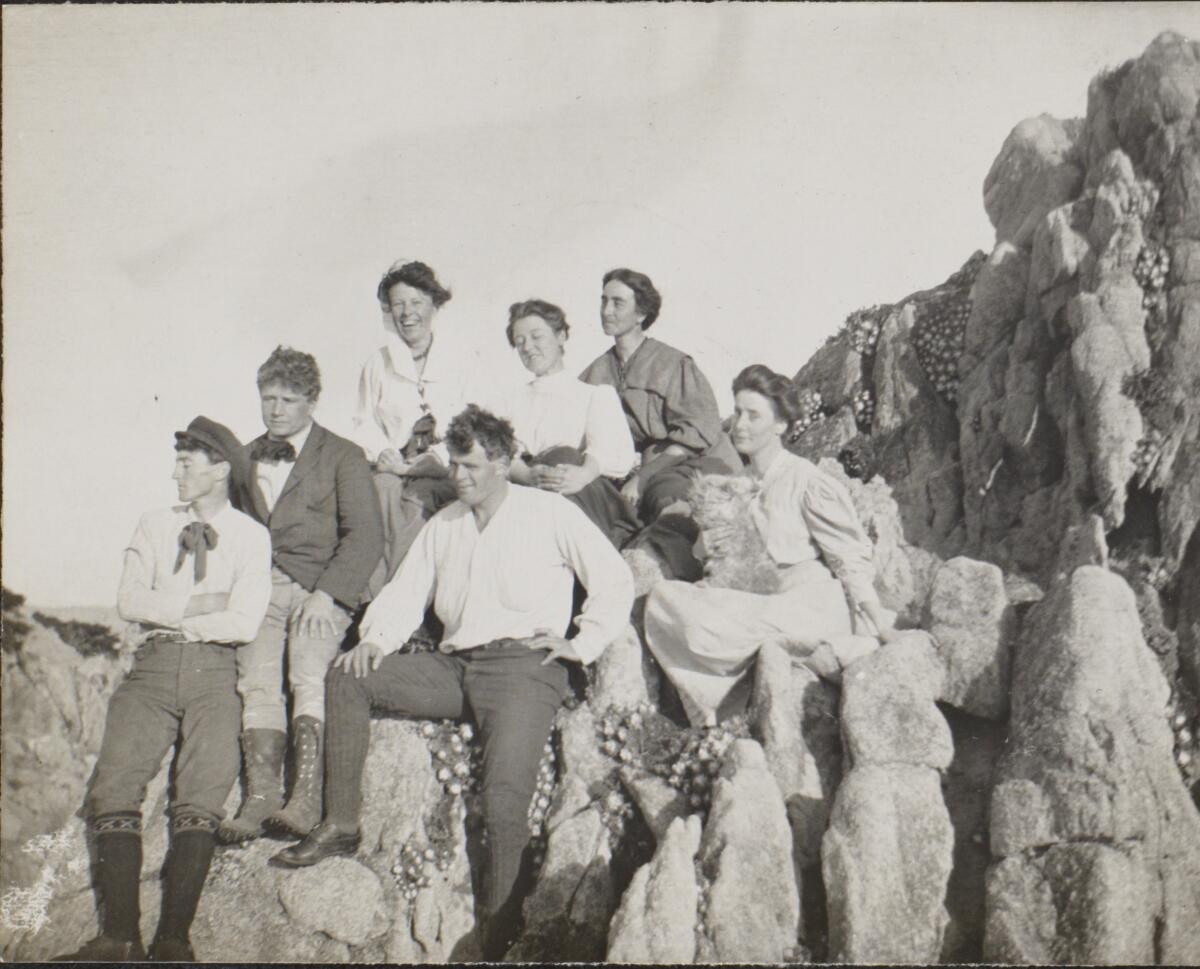

Nora May French is only part of the story. “The Gilded Edge” revisits the early 20th century colony at Carmel-by-the-Sea: famous for hosting writers including Upton Sinclair and Jack London; scandalous in its time for drunken orgies; notorious ever after for a love triangle and a suicide that inspired multiple copycats not only within the colony, but across the country.

Prendergast is a professor of English at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, has been a Guggenheim fellow and a Fulbright scholar, and typically traffics in academic monographs on topics like school desegregation, racial justice and disability rights. But as a self-described “archive rat,” she couldn’t resist the rabbit hole of a mysterious female poet who died by her own hand — or did she?

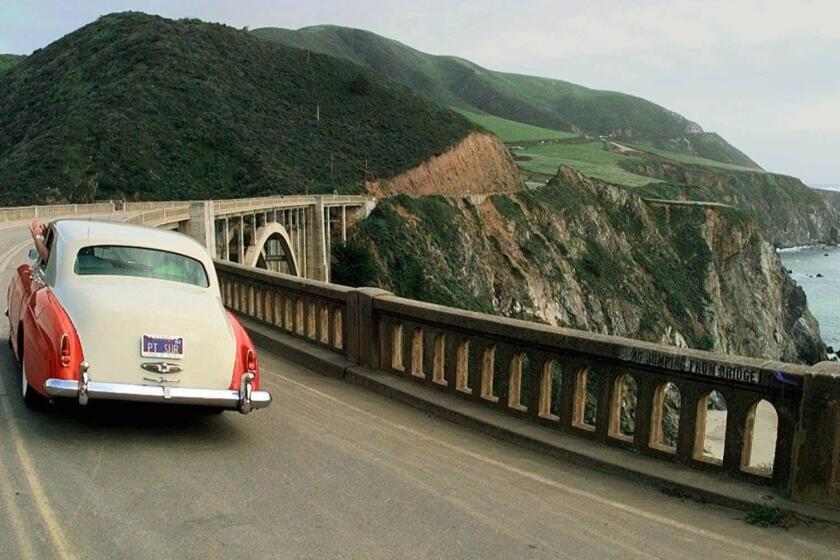

Big Sur isn’t a clearly demarcated space on the map so much as a general location in our collective state of California-dreaming.

French was an enormously talented poet surrounded by male counterparts who were, to put it simply, hacks. Prendergast contrasts poems written by French and another member of the Carmel writers’ group, George Sterling. The difference is clear even to a non-poet. “It’s drivel,” Prendergast says of the man’s verse.

ravi

Yet it was Sterling who gained the patronage of the famous writer Ambrose Bierce, Sterling who was named the poet laureate of San Francisco. Carrie Sterling, George’s wife, grew up in poverty. After their marriage, the two socialized with the wealthy elite of San Francisco. Eventually they settled in Carmel, where they set out to create an artists’ enclave.

There the couple spent much of their time charming writers and artists they hoped would buy property in their “colony.” Prendergast sees the Sterlings as the prototype for what we now call influencers. That is, people who leverage their celebrity to sell things. What they were selling, in short, was a “bohemian chic” way of life — a romanticized version of artistic poverty that must have privately irked George’s once-impoverished wife.

The Sterlings hosted authors with national reputations and gave them the real estate multilevel marketing hard sell; their early buy-in would entice lesser-known artists and raise their property values in the process. As Prendergast discovered, Asian Americans and wealthy Black people were actively discouraged from living there. The dark side of the pastoral ideal promoted by such colonies was the implicit escape from the multiethnic masses of the cities.

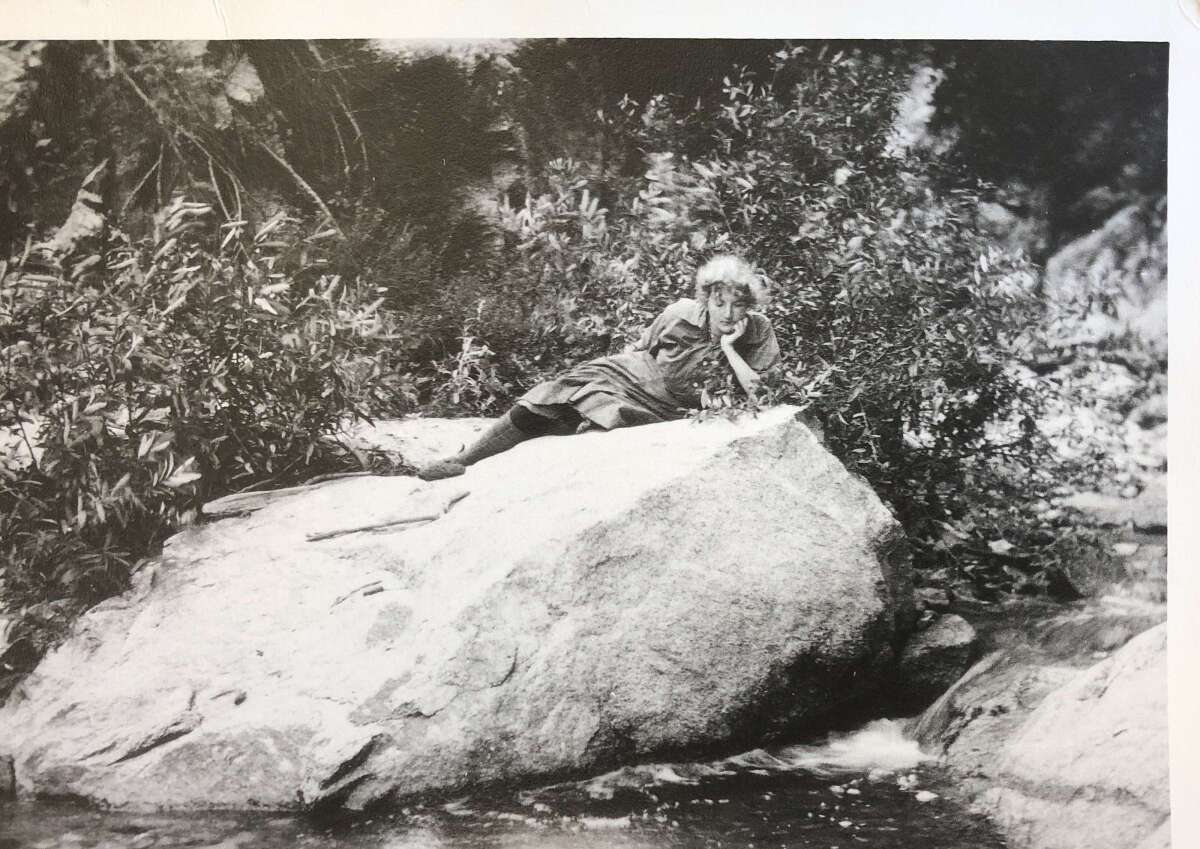

The Sterlings met French and, taken by both her beauty and her talent, set her up in a guest cottage on their property. A single woman living with a married couple in 1907 raised eyebrows. George already had a reputation as a serial philanderer, and, true to form, he and Nora became lovers. One weekend, while George was away, Nora swallowed cyanide and died. Carrie found the poet’s body, and hers is the only eyewitness account of the events of that night. But what really happened?

French’s death is often assumed to have precipitated the collapse of these early 20th century bohemians. But Prendergast says her research doesn’t support that conclusion. “The truth behind what happened is both more intimate and more sordid and sadder and more important than what became a good story to sell Carmel.”

Marie Mutsuki Mockett’s ‘American Harvest’ looks at the divide between the heartland and those who seldom think about where our food comes from.

The demise of the beautiful lady poet was reported breathlessly by the national press, leading to copycat suicides. Eventually, both Sterlings would also meet untimely ends. It was in keeping with Carmel’s scandalous reputation, including tales of Jack London’s debauchery. What’s astonishing about Prendergast’s research is that it uncovered wilder stories that the yellow press missed — including a fistfight that broke out during French’s memorial service.

For the record:

9:57 a.m. Oct. 20, 2021An earlier version of this story misspelled the name of a University of Illinois historian as Donna Ravine. It is Dana Rabin.

Ultimately, “The Gilded Edge” takes on the cast of a great detective novel — albeit one without a tidy conclusion. One barrier to getting to the bottom of the deaths was the lack of material on the women, compared to the glut of news about the men. “I had a heart-to-heart with my colleague in history, Dana Rabin, about what I was trying to reconstruct,” Prendergast recalled. “And she said, ‘You’ve got a choice in women’s lives. They’re not as well recorded. So what are we going to do? Are we going to write about the men over and over again? Or are we going to try to make a good faith effort to bridge the gaps?’”

Prendergast does that by recounting her personal reactions to material she did discover — as well as the answers that eluded her. “I made a conscious choice that I was going to find as much as possible and then write my way through the gaps,” she said. “The more transparent we are, the more transparent it becomes.” Histories are always works of interpretation. Prendergast wanted to make sure readers knew that.

The reader as detective may draw her own conclusions, and the author listened patiently as I told her what I thought had happened to French. She said her agent and her editor — the book’s two closest readers — have “completely divergent views” on French’s fate.

Seven years after she discovered French’s letter, Prendergast has ample evidence of the continued relevance of this neglected poet hemmed in by smaller men: “How dare we, in our year of our Texas law, 2021, where bounties are being put on women’s heads for doing exactly what Nora French did, assert that we have in some way progressed from this woman a hundred years ago?”

One more continuity: In 2021, literary gossip can dominate Twitter for days at a time. In 1907, the national press plastered their pages with photos and drawings of French. Yet 100 years later, most of us have never heard of her, despite her obvious talent and scandalous end. The mystery surrounding Prendergast’s mystery is why French disappeared from public discussion so quickly after the hullabaloo died down. That disappearance is an integral part of the story Prendergast tells. What it reveals about gender and the arts is perhaps the least surprising aspect of this unpredictable and addictive story.

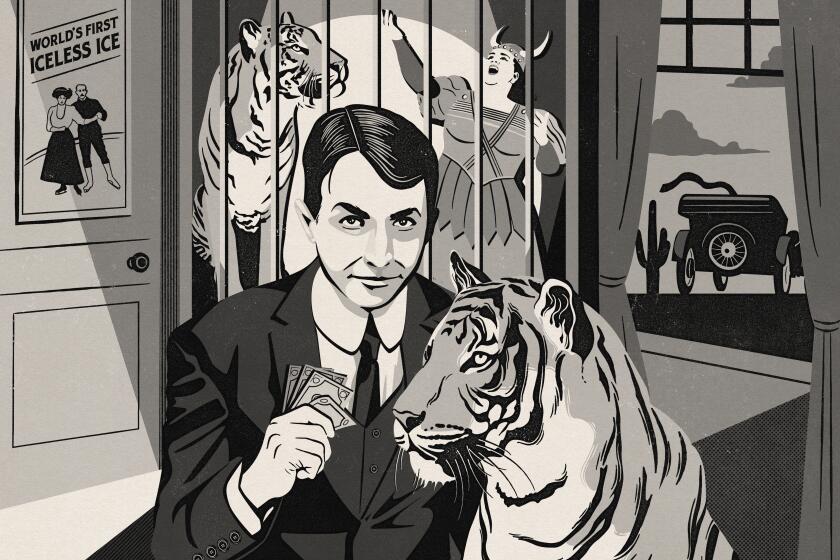

Hollywood scamming is a tradition. The century-old saga of Paul Bourgeois — cinematographer, animal wrangler, con artist — shows how far back it goes.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.