“Take me through publishing a book,” Michelle Tea tells Hedi El Kholti. The longtime friends sit together in the office of the Highland Park home El Kholti shares with his partner, renowned Irish novelist Colm Tóibín. They are here today to make a new publishing company.

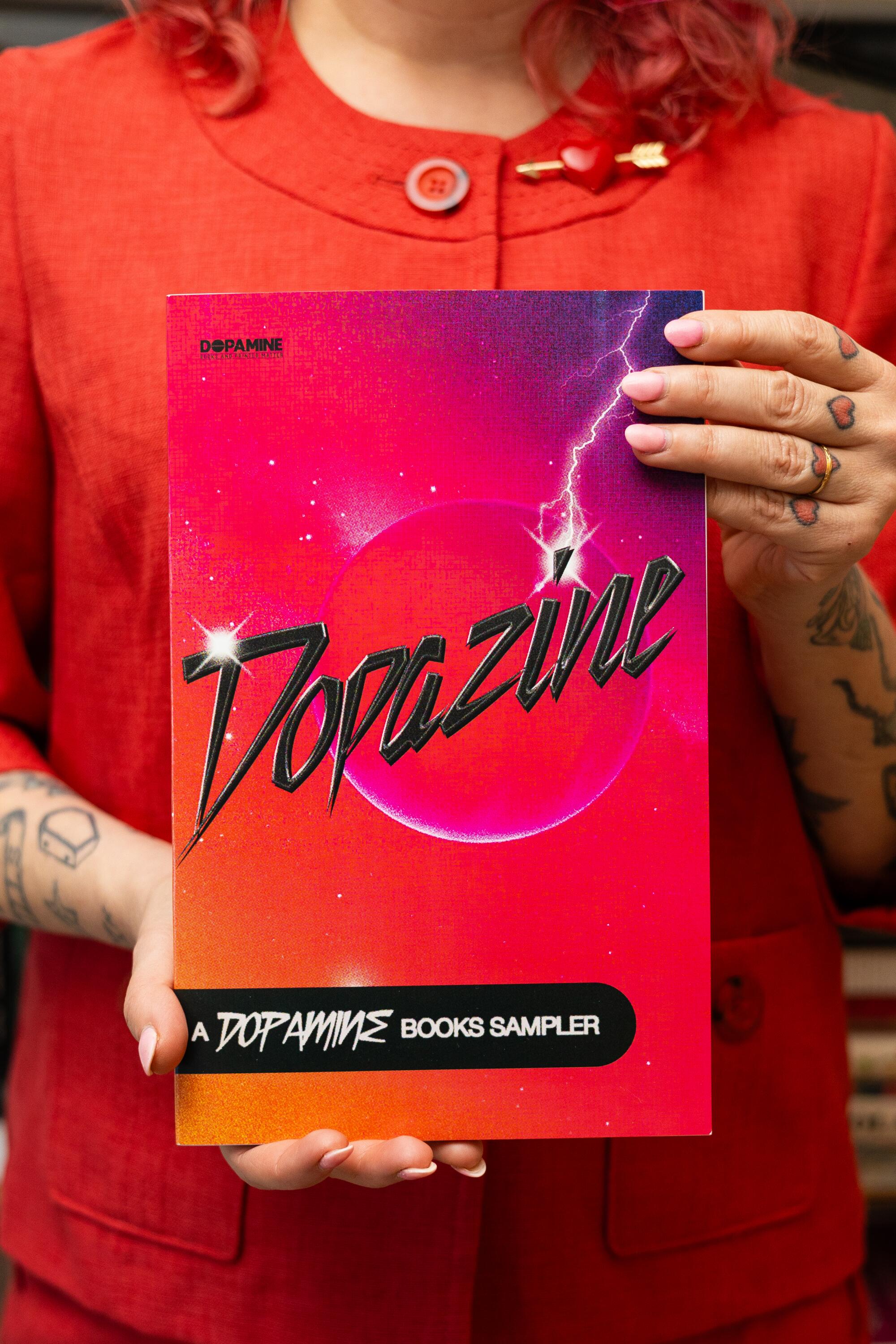

El Kholti, 56, is the co-editor of Semiotext(e), the 50-year-old indie publisher of such iconoclasts as William S. Burroughs, Eileen Myles, Andrea Dworkin — and, in 1998, Tea’s first novel, “The Passionate Mistakes and Intricate Corruption of One Girl in America.” Tea’s new press, Dopamine, which will release its first book next May, will be published through Semiotext(e), but it will be as independent as a small arm of a small press can be.

For the record:

4:37 p.m. Dec. 19, 2023An earlier version of this piece stated that Michelle Tea created the first Drag Queen Story Hour. While Tea did launch the series under that name, it was not the first event to feature drag queens reading for children.

Tea, 52, is a Massachusetts-to-San Francisco-to-Los Angeles transplant — and the literary lioness who pioneered, among many other cultural lightning rods, the notorious Drag Queen Story Hour. The self-described “queer, feminist, punk and working-class” poet burst onto the San Francisco scene in the early 1990s. She co-founded the feminist collective Sister Spit, hosting queer open mic nights around the city and, later, homespun tours of spoken word artists in bars, galleries, bookstores and living rooms around the world. In 2012, Sister Spit spawned a publishing imprint at City Lights Books, which Tea ran until the Feminist Press invited her to helm her own imprint, Amethyst Editions, in 2015. Tea left Amethyst four years later.

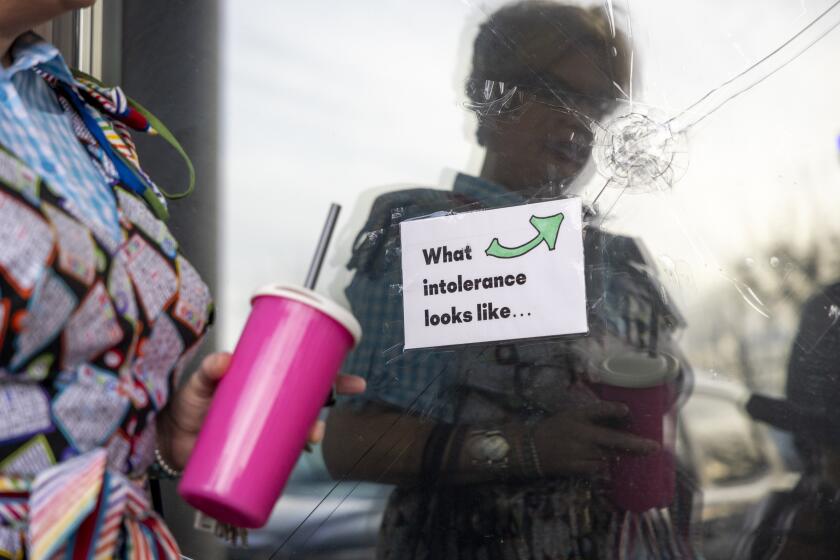

Drag queens are more mainstream than ever, as are LGBTQ rights. Yet, story hours, where drag queens read to kids, have become a point of controversy and even violence.

“The only problem I had with City Lights and Amethyst was not having control over what I could publish,” Tea explains. “Work I adored was slipping through my fingers, which was frustrating enough to inspire me to walk away.”

After months of mulling her options, Tea decided to make her pitch to El Kholti last May. She asked him to meet her at Found Coffee in Eagle Rock, where she told him she wanted to start a press “dedicated to stylistic stories of unvarnished queer existence.”

El Kholti recalls his response: “I offered to put our infrastructure at her disposal, no strings attached. The mainstream presses have made an effort to be more inclusive of queer writers in the last few years, and that’s great. But Michelle will publish things that no one else would.”

Over lattes, the two agreed that Dopamine would be editorially independent — a crucial deal point for Tea. Their handshake deal involved zero dollars, paperwork or specifics, but stipulated Dopamine’s inclusion in the Semiotext(e) catalog and in its printing-and-distribution deal with MIT Press.

On our way to El Kholti’s house, I asked Tea why she’s starting yet another imprint. “I came up in a literary community that didn’t think being published was an option,” she answered. “We were queer, unconnected. We hadn’t gone to college. So the thought of publishing queer works that might be overlooked within capitalism feels like the work I’m meant to do in this world.”

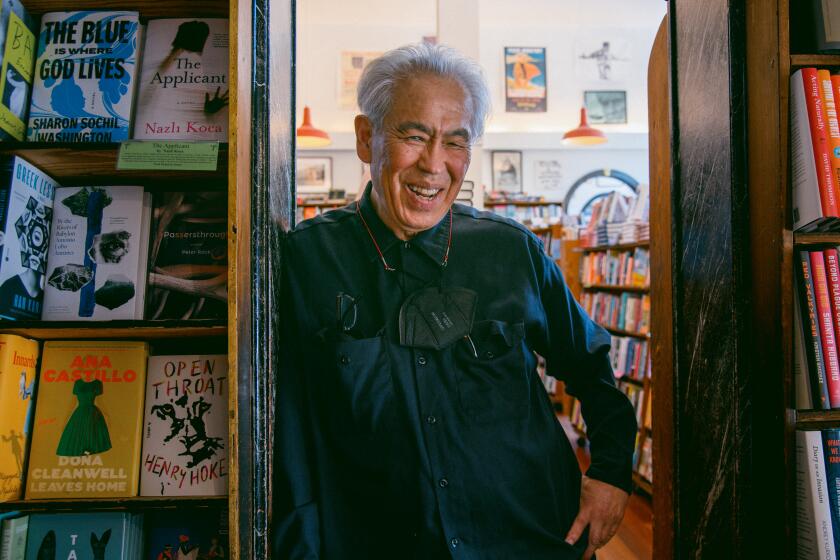

Van Nuys native Paul Yamazaki, a longtime veteran of San Francisco landmark City Lights, will receive a lifetime honor at the National Book Awards next month.

In August, Dopamine held its first event: a sold-out, $100-per-person fundraiser at Glendale’s community arts space, Junior High. It was a raucous evening of spirited performances by forthcoming Dopamine authors, interspersed with grab-bag giveaways donated by local alt-artists including Miranda July, Maggie Nelson, Mimi Pond and Dopamine CFO Beth Pickens.

“We are not a press that is taking the pulse of the market and allowing that to dictate our titles,” Tea explained from the makeshift stage. “My goals are simple. To have this press sustain itself so we’re less reliant upon the generosity of others. And to bring exciting new work into the world.” Days after the event, Dopamine went public, loud and proud, in a full-page Publishers Weekly story.

A month later, back at El Kholti’s Highland Park office, the conversation is all nuts-and-bolts.

“Let’s talk about ‘Sluts,’” El Kholti says to Tea, referring to the anthology that will be Dopamine’s first title. “It comes out in May ‘24, right?”

Tea nods. “What will the galleys look like?” she asks. (Galleys are early copies sent to booksellers and reviewers ahead of publication.) El Kholti pulls two Semiotext(e) galleys out of the pile on his desk, hands one to her. “This looks so good,” she says, paging through. El Kholti does the same with his copy.

“About the cost,” Tea says. “I want this to be as light on you as possible. You’re doing me such an amazing favor.”

Printing galleys, he informs her, costs between $5 and $10 a copy.

Tea frowns, scribbling into a notebook.

“I could order your galleys from the MIT guy,” El Khoti says. “I’ll pay him, and you can pay me back.”

“So, you’re piggybacking on MIT, and I’m piggybacking on you,” Tea concludes. El Kholti nods.

Tea turns to me, grinning ruefully. “I’m glad I didn’t know how complicated and expensive this would be before I agreed to that PW story. You make this grand announcement, then you actually have to do the thing.”

…

The U.S. publishing industry was born in Massachusetts in 1640, with the printing of “The Whole Booke of Psalmes” on an imported British press. According to the late Al Silverman, onetime head of the Book of the Month Club, the industry’s “golden age” blossomed between 1946 and the early 1980s.

“Is the Publishing Industry Broken?” Publisher’s Weekly asked in 2022, quoting insiders who described “an intensifying corporate culture … and the creeping feeling that they’re pushing a product more than a passion.”

Book publisher Simon & Schuster’s sale to investment firm KKR is novel in many ways, but also part of a long-term trend. History tells us to expect the unexpected.

“Another result of consolidation,” a veteran agent told PW, “is that the big houses are not willing to buy more experimental books. It’s always been true, but it has gotten worse.” The piece also quotes superagent Robert Gottlieb: “As publishing has evolved from a cottage industry into one full of corporate multinationals, publishers’ expectations for their return on investment has become much more substantial.”

These new parameters have exerted unsustainable pressure on publishers, including its behemoths. In 2013, giants Penguin and Random House merged; this year the Department of Justice blocked Paramount’s attempt to sell Simon & Schuster to that conglomerate, now called Penguin Random House. Instead, Simon & Schuster was sold to a private equity firm. PRH, now saddled with debt, has laid off dozens of employees, including some of its most legendary editors: the keepers of the flame, whose allegiance was to literature, not lucre.

To those who prefer to write and read a wider range of books, these changes sound a death knell. An industry that increasingly relies on its hugely profitable 1% — sure-fire bestsellers like Danielle Steel, J.K. Rowling, Stephen King and James Patterson — has zero tolerance for the kind of “experimental” work (too often, code for queer writing) craved by Tea and El Kholti and untold numbers of left-behind readers.

Dopamine’s business model will be radically different. Writers will be paid a small, no-strings “commissioning fee.” Unlike the traditional book advance, it won’t have to be repaid before the author sees a penny of royalties. Instead, each writer receives 10% of the retail price of each copy sold. It’s an attractive proposition for first-time authors who face impossible odds of success with a Big Five house. Even if they manage to snag a deal, their books are likely to be drowned out by the bestsellers’ noise.

If Dopamine, with its low, labor-of-love operating costs, proves economically sustainable, it could be a life preserver in a perfect storm.

For the authors Tea has signed to Dopamine, it already is.

When publishers Rare Bird and Unnamed Press moved into Highland Park, North Figueroa Bookshop soon followed, putting down roots in a bookstore-starved neighborhood.

“I wrote my novel because of Michelle,” says Clement Goldberg (who uses they/them pronouns). “New Mistakes,” about a young woman attempting to get her life together after being dumped by a throuple, will be their first book. Goldberg and Tea have been friends since 2005 and collaborators since 2013, when Goldberg made a multi-filmmaker movie of Tea’s cult-favorite novel “Valencia.” “That epic collective undertaking was one of the highlights of my career,” Goldberg says.

In 2022, Tea read “New Mistakes” in its original form — as a script for a TV series. “Michelle said if I turned my script into a novel, she’d pledge her life to getting it published. A little more than a year later, I’d written a novel, and she was starting a press! Michelle told me I could make more money selling the novel on the open market. But Dopamine had my heart. In such a dangerous moment to exist as a queer and trans person, I’d much rather be with writers and artists in the same boat, steered by a publisher who’s already on board.”

Vera Blossom, who calls herself “a proud Filipina American transgender monster,” is also releasing her first book, “How to F— Like a Girl,” with Dopamine. She, too, says her debut “would not exist if I had never met Michelle, point blank. I’ve worked hard to carve out space for myself to exist unapologetically. When I found Michelle, I discovered that she’d already built an entire world for me to explore and be free in.”

Like Goldberg, Blossom believes the upside of publishing with Dopamine far exceeds the risk. “I knew what it would take to get this weird memoir published without Dopamine: packaging myself and my tale for strangers, wondering if I could trust them with my story,” she says. “Or I could go on this adventure with a friend and queer literary trailblazer who I deeply admire and trust. The decision was easy.”

“Days Running,” forthcoming from Dopamine in 2024, is the second novel in a trilogy by Shawn Stewart Ruff. He describes the first in the series,“Finlater,” as “a highly sexual first-love story about a Black boy and Jewish boy, which was dismissed and regarded with disgust by every agent and editor who saw it.”

Even as Justin Torres was riding accolades for his debut novel, ‘We the Animals,’ he was on a 12-year journey to a wilder, deeper follow-up, ‘Blackouts.’

After two years of “feeling demoralized and shelving ‘Finlater,’” Ruff explains, “I took the advice of a wise artist friend and self-published it. Neither of us imagined the book would win a Lambda Literary Award for debut fiction. So, with ‘Days Running,’ I decided to leave my Park Avenue agency, skip the big publishing houses, and try my luck with a small press.”

Ruff has self-published several other books; only his anthology of queer African American fiction, “Go the Way Your Blood Beats,” was picked up by a mainstream publisher. He has known Tea since 2008, when she invited him to read from his debut at a San Francisco reading series. “When I learned of Dopamine, I wrote her asking if I could help somehow. I also mentioned my new book, with fingers crossed. And, well, here we are.”

Unlike Dopamine’s debut authors, Ruff was drawn to the house because of his years of experience. “At the start of my career,” he says, “what mattered to me was brand recognition and bragging rights that a big house had chosen me. Now I care more about artistic freedom and being among writers, editors, thinkers, publishers who celebrate the breadth of queer culture. Only a small press can do this.”

Tea’s plan for Dopamine is to keep to the vision that has lit her way so far. “Authors like Clem, Vera and Shawn are the reason for Dopamine’s being,” she tells me on the drive home. “They deserve to be represented and supported by a publisher who knows and understands them.” But to define her new project as a business, she believes, is to miss its true essence.

“Dopamine is an expression of queer joy and liberation,” Tea says. “It gives people who wouldn’t otherwise be heard the freedom to express our weird, un-assimilated selves, tell our stories, and celebrate the intricacies of queer lives on this planet.”

Maran lives in L.A. and is the author of “The New Old Me” and a dozen other books.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.