Review: Remember when we looked forward to the future? A new series revives ‘Radium Age’ sci-fi

On the Shelf

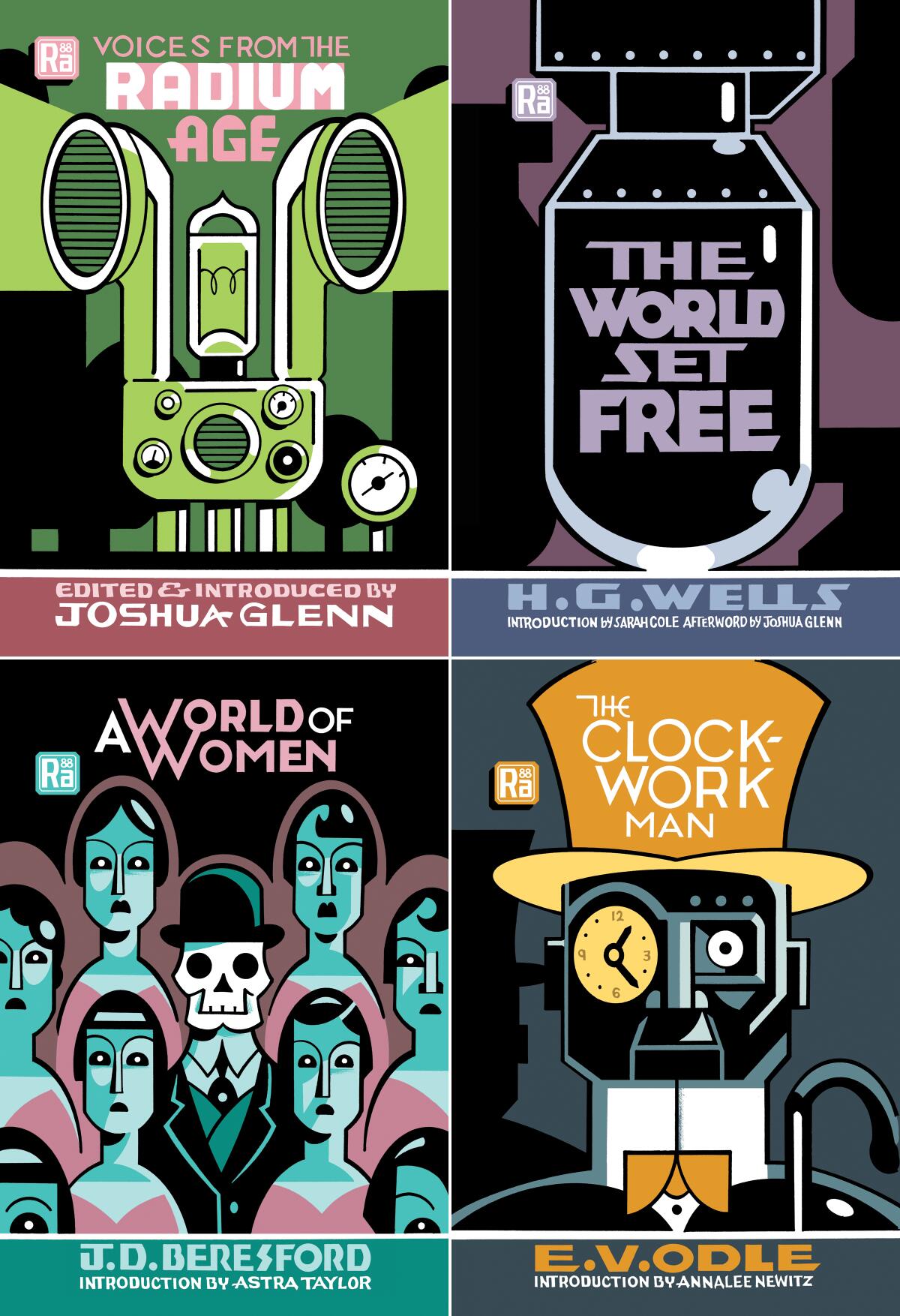

The Radium Age Series

Voices from the Radium Age

Edited by Joshua Glenn

MIT: 224 pages, $20

A World of Women

By J. D. Beresford

MIT: 340 pages, $20

The Clockwork Man

By E. V. Odle

MIT: 202 pages, $20

The World Set Free

By H. G. Wells

MIT: 282 page, $20

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Long live the Radium Age, which was (at the very least) a good deal less horrific and disquieting than the one we’re in now. Back then, the future possessed an almost mystical glow of strangeness that wasn’t simply terrifying; and while it often promised calamities or even a halfway decent apocalypse, these sudden shifts could potentially open up the world to refreshed and invigorating possibilities.

“Radium Age” is the coinage of Joshua Glenn, editor of a new MIT Press series under that title, with four books published so far this year, covering what Glenn calls science fiction’s “pre-golden age,” from roughly 1900 to 1935. If the Atomic Age was built on the idea that the future might be one huge explosion, the Radium Age emerged, somewhat more optimistically, from the discoveries of Marie Curie — and the suggestion that our universe of infinite energy was “constantly in movement.” All sorts of extraordinary things might happen at any moment in such a universe: Women might win the right to vote, working class people might unionize, African Americans might fully emerge from slavery. It was a marvelous time to imagine the future — a time when the future might still be something to look forward to.

In his series introduction, Glenn describes Radium Age fiction as a form of “proto sf.” What’s not always clear, however, is what unifies it generically or thematically. H.G. Wells’ “The World Set Free” (1914), the most recent release in the series, is a docudrama-style tale of a WWI that might have been, told from various viewpoints across a war-fractured planet. (The real WWI, which began that same year, proved almost as horrible as the one Wells had imagined.)

“Set Free” envisions the development of nearly infinite sources of power — which, wielded by divided nations, results in unprecedented mass slaughter. For Wells, the “logical” result of such violence would be that nations would band together under one “sovereign” force — science, or what Wells calls “the mind of the race.” It is not one of Wells’ best novels, far less captivating than “Things to Come” or even “The Time Machine.” But like everything he produced it brims with thoughtful, hopeful narrative energy.

When COVID-19 put comics on pause, Winter Soldier co-creator Ed Brubaker embarked on a new project — the Reckless series of L.A. pulp graphic novels.

The two other novels published so far, also both British, feel less like predictions than satires on the Victorian culture that produced them. In E.V. Odle’s “The Clockwork Man” (1923), a visitor from the future turns out to be a largely mechanical contraption who can wind himself up to function as mindlessly as any human cog in an assembly line. But the best of this early lot is easily J.D. Beresford’s “A World of Women” (1913), whose March release was its first U.S. appearance in print for many decades. It’s the sort of post-apocalyptic novel British writers have always excelled at, from Richard Jefferies to John Christopher. (The British apocalypse often feels like a mildly exhilarating release from class-bound island culture.)

Beresford was a clergyman crippled by polio — and an early critical enthusiast of Wells — who envisioned how one male-hating virus could transform Britain into a feminist utopia where the few surviving men are paraded about in their rooster-like finery while women do what was once considered “man’s” work. As in most “feminist” dystopias, from Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “Herland” (1915) to Joanna Russ’ “The Female Man” (1975), “World of Women” doesn’t see losing half the adult population as necessarily a good thing — but it definitely makes life quieter and more peaceful.

Faced with a deadly virus, Beresford’s politicians sound an awful lot like our own, dragging their heels on shutdowns for fear of alienating their financial backers. “Are we all cravens,” they ask themselves, “scurrying like rabbits to our burrows at the first hint of alarm?” No, they aren’t craven; mostly they just die. Long before “Don’t Look Up” or “The Handmaid’s Tale,” Beresford didn’t bother predicting the future; he simply explored the stupidities of the present.

At least five more Radium Age books are set for release by authors ranging from Rose Macaulay to Arthur Conan Doyle. The series promises to be fascinating, though a mixed bag. The most mixed of all is the first entry, published in March, a “taster’s choice” of tales published as “Voices From the Radium Age.” They include a couple of notable “recoveries,” such as a 1908 feminist utopia from the relatively unknown Bengali author and teacher Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain and W.E.B. DuBois’ “The Comet,” still readable after all these years, about how a collision of planetary bodies reshuffles the world’s racial conflicts. These stories are more political allegory than science fiction; regardless, they both seem worthy of being recovered.

Kate Folk’s story, ‘Out There,’ made waves for its male androids catfishing women. Her new collection further dissects gender through a sci-fi lens.

Then there is William Hope Hodgson’s “The Voice in the Night,” the tale of a man and his fiancée being taken over by a bizarre sea fungus, which is more like the “supernatural” stories of Algernon Blackwood or H.P. Lovecraft. And there is E.M. Forster’s fairly well known, readily available “The Machine Stops,” about a future Earth in which a global computer does everything for everybody until it breaks down and stops doing anything for anybody. A fun surprise is Jack London’s “The Red One,” a marvelous tale of a jungle explorer encountering a representative from outer space.

The collection closes with what feels like the most red-hot Radium-ish story of them all, Neil R. Jones’ 1931 tale, “The Jameson Satellite.” Jones was a New York State civil servant who investigated unemployment claims; he seemed creatively unconstrained by scientific knowledge. In this first of a popular series of novelettes, Professor Jameson launches his dead body into orbit around the Earth; after 40 million years he is rescued by a cyborg-race known as the Zoromes, who revive Jameson’s brain and plant it in a glimmering chrome body just like theirs. Then they embark on a series of adventures that are just as much fun to read today as they must have been nearly a century ago. As in the great Doctor Who, “science” is just a gimmick to move plots along as quickly and wildly as possible. Anyone who reads them to learn anything useful is barking up the wrong spaceship.

It’s unclear yet whether the series is dedicated to publishing significant books in the history of sci-fi (Pauline Hopkins’ “Of One Blood,” often credited as the precursor of Afrofuturism, is coming in August) or simply bringing back anything odd that might come along. What’s missing so far — with the possible exception of the Professor Jameson story — are those many writers who energized early sci-fi with their odd brands of scientific-romance and stellar-visioning. To take Californians alone: the far-future extrapolators Leigh Brackett and Clark Ashton Smith; or the great husband and wife team of C.L. Moore and Henry Kuttner.

Critics and Cassandras of our thralldom to secondhand experience via the Internet are hardly scarce — Jaron Lanier, Evgeny Morozov, and Clifford Stoll are only among the most cogent.

However the series develops, it is already making available some great (or at least significant) fiction that usually offers a much brighter future than many of us can bring ourselves to hope for anymore. Like that happiest of filmic anachronisms, “Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow,” these stories fizz and pop with something much better than believable possibilities. They remind us of how joyful the future once seemed.

Bradfield is the author of “The History of Luminous Motion” and “Dazzle Resplendent: Adventures of a Misanthropic Dog.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.