The Black women’s group that helped launch Toni Morrison, Alice Walker and a new vanguard

Review

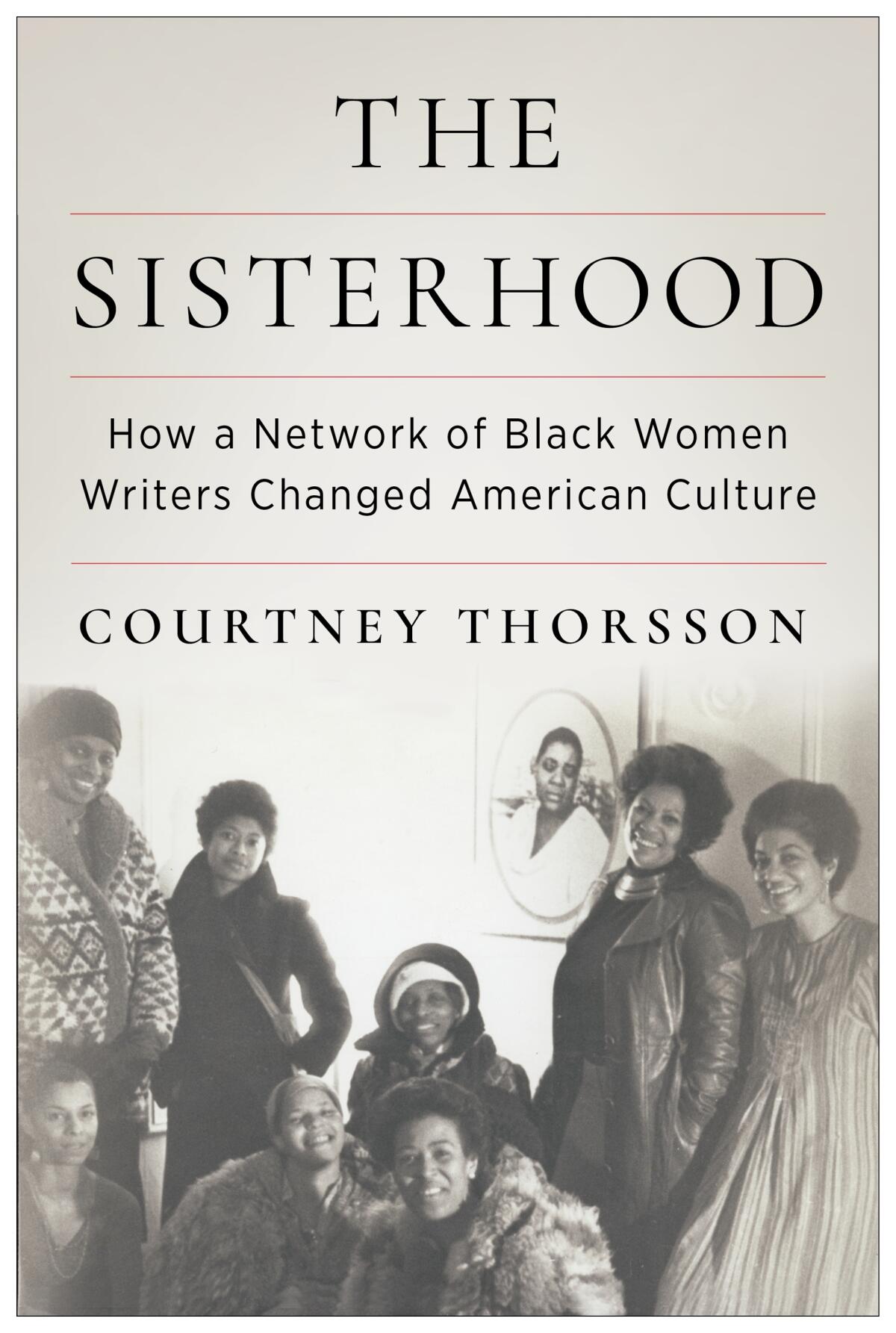

The Sisterhood: How a Network of Black Women Writers Changed American Culture

By Courtney Thorsson

Columbia University Press: 296 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In 2004, as a graduate student, Courtney Thorsson learned about a snapshot taken of some of the greatest American writers. No, no one captured Phillip Roth, Saul Bellow and John Updike hobnobbing with the Jonathans. The writers in question included Toni Morrison, June Jordan, Alice Walker and Ntozake Shange. This was an intimate image of friends at the end of a Brooklyn party where they had dined on gumbo and sipped Champagne. Each smile glows with pride, openness and joy. It was the first gathering of the Sisterhood.

Unwilling to leave this photograph in the archive, Thorsson, now an associate professor of English at the University of Oregon, decided to exhume the story behind the image. Her new book, “The Sisterhood,” dives into the sociocultural discourse of the 1970s in order to trace the trajectory of authors who transformed and elevated American literature in the decades that followed. Unfortunately, in a broad attempt to stress her message of the power of community, rather than let the figures and their work speak for themselves, Thorsson frames the book as a thesis in search of evidence.

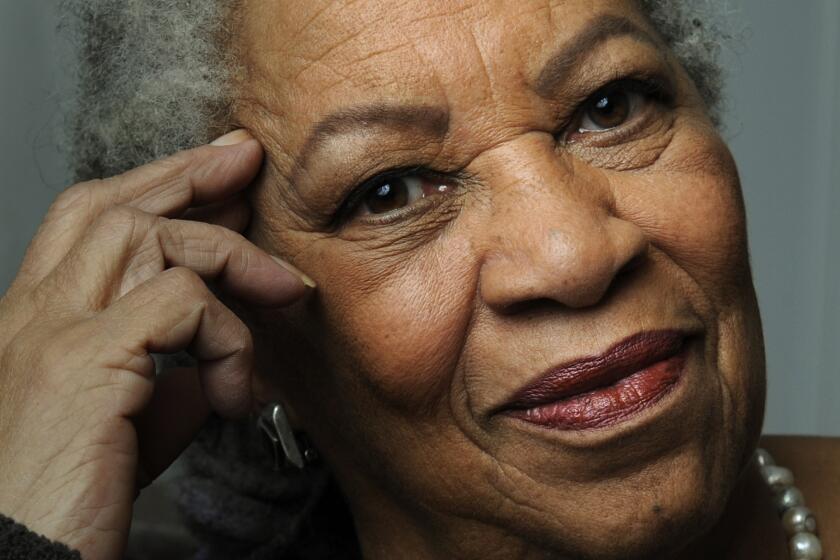

Toni Morrison, the author, essayist and winner of Nobel and Pulitzer prizes, famously encouraged would-be writers to take action.

The Sisterhood was a collective of Black female writers who met monthly at the homes of its members in New York City to collaborate and commiserate over their cultural work. First convened by Jordan and Walker, it quickly and organically grew outward, drawing together women of all ages and experience. While the group evoked the emotional echoes of a consciousness-raising session, it was an ambitious, professional project as well. Members collected dues, helped one another place their stories and showcase their work and even contemplated establishing a business and a periodical. Yet it was a short-lived endeavor. From 1977-78, this dream team of Black female writers pulsed with hope and drive.

The fortifying spirit of this brain trust is mind-blowing to imagine. When I mentioned this story to friends, one said, “This sounds like the premise of a movie.” And it does: seasoned professionals finding energy in the enthusiasm of young upstarts, who are themselves eager to step out of the secretarial pool and into the front windows of bookstores across America. More than 45 years later, the greatest gift of learning about this group is a bittersweet knowledge that its members so deeply appreciated one another. Sometimes they succeeded and sometimes they faltered, but they shared it all together.

Perhaps it was too good to last; this fleeting collective came together during a turbulent time in American history and served as the crucible of a renaissance in African American literature. In the decade that followed, Black women stepped into the spotlight of American fiction with works including Walker’s “The Color Purple,” Morrison’s “Beloved,” Jordan’s “Passion,” Audre Lorde’s “Sister Outsider” and many, many others. Walker, Morrison and critic Margo Jefferson received Pulitzer Prizes. Other accolades include the National Book Award and yes, in time, Morrison’s Nobel.

Such greatness can flourish without the encouragement, shared resources and emotional labor of one’s peers. But if not for their connections and support as a group, would as many of these women have succeeded despite the obstacles presented by racism, sexism, classism and homophobia? Thorsson recognizes extraordinary personal achievements, but her book is a testament to the power of the collective.

Starting with such great characters, one could take this book in multiple directions. Instinctively, I assumed this would be a group biography, a carefully embroidered portrait of a cultural moment and its relevance. Thorsson, however, lays it plain: “This is not a group biography, but I do seek to capture these Black women writers at a pivotal time in their intellectual lives.”

Nevertheless, several figures stand out: Morrison, Jordan, Walker, Shange and Lorde. In the face of these legends, the secondary characters fall into the shadows. While I respect Thorsson’s urge to eschew the biography format in order to speak to the collective work, I wonder at the editorial decision to occupy the murky middle of general nonfiction when you have such vibrant individuals at hand.

Thorsson excels at drawing connections among the members and elaborating on their efforts, but she does so by telling and not showing them. She writes, for example, that Walker and Jordan “exchanged letters about personal and professional matters for years before they established the group and were united by what Cheryl Walls calls ‘their lifelong quest for a redemptive art and politics.’” Why not quote the letters, or at least describe them directly?

As it stands, the reader longs for more stories, more anecdotes, more retellings of events from the members’ point of view. Instead, the book is mired in repetitive and academic assertions of her thesis: that the cumulative impact of various groups (not only the Sisterhood, but also the Black Arts Movement and other Black organizations) endowed writers with the strategies and focus to change American culture. Grounded in this perspective, Thorsson balks at what she considers exceptionalism, but why not celebrate both the individual achievements and the collective legacy? In parsing her own struggle, Thorsson loses momentum.

Meanwhile, she makes her own tenuous assumptions. For just one example, she ascribes the motivation behind a 1988 open letter protesting the lack of major accolades for Morrison to a collective decision “that there could only be one highly successful Black writer at the time.” This is a reductive interpretation based on scant evidence, and it contradicts Thorsson’s argument for collective success.

Black horror pioneer Tananarive Due helps us pick 6 great books from the genre, from a Toni Morrison classic to a new anthology by Jordan Peele.

At the end of her introduction, Thorsson notes that she is a white scholar of Black literature. “It is my responsibility … to use the privilege of my whiteness, institutional affiliations, and skills as a literary scholar to get as many people as possible to read, reread, and better understand as many books as possible by Black writers.” Her hope is that the book may “help us understand their remarkable achievement, the costs of their work, and the labor that remains to be done.”

As a white critic writing about these same Black women, perhaps I too should make clear my limited perspective. But when you’re elevating a forgotten moment in history, you should acknowledge but wear lightly your self-conscious intention to impose predetermined ideas about it.

Whatever my qualms with her style and editorial decisions, I remain grateful to Thorsson for bringing to light the Sisterhood’s existence and collective work. Rather than wish for a different book, one rich in research but elevated through narrative and voice, I’d encourage others to go back and reread (or read for the first time) the great works of the Sisterhood with an eye for their attention to kinship and collaboration, as well as to individual glory.

LeBlanc is a writer and a board member of the National Book Critics Circle.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.