Appreciation: Toni Morrison was both a mirror and a map who reflected experience back to us

For as long as I can remember, the publication of a new Toni Morrison book was like a visit by a dignitary, but a figure who also was family. Room was made, time was cleared to sit with her.

She always arrived with the stories we needed to hear, when we most required them. These were accounts that weren’t full of sun or easy resolutions. Nothing about them was “escapist,” though they were often full of deep love and magic. She offered up difficult predicaments, examined lives that didn’t have sure or clear arcs and African American characters who made busy life quilts out of the castoff pieces they had gathered. Her stories often investigated heartbreak — the transformative kind — the trauma that you survive that doesn’t break you but remakes you.

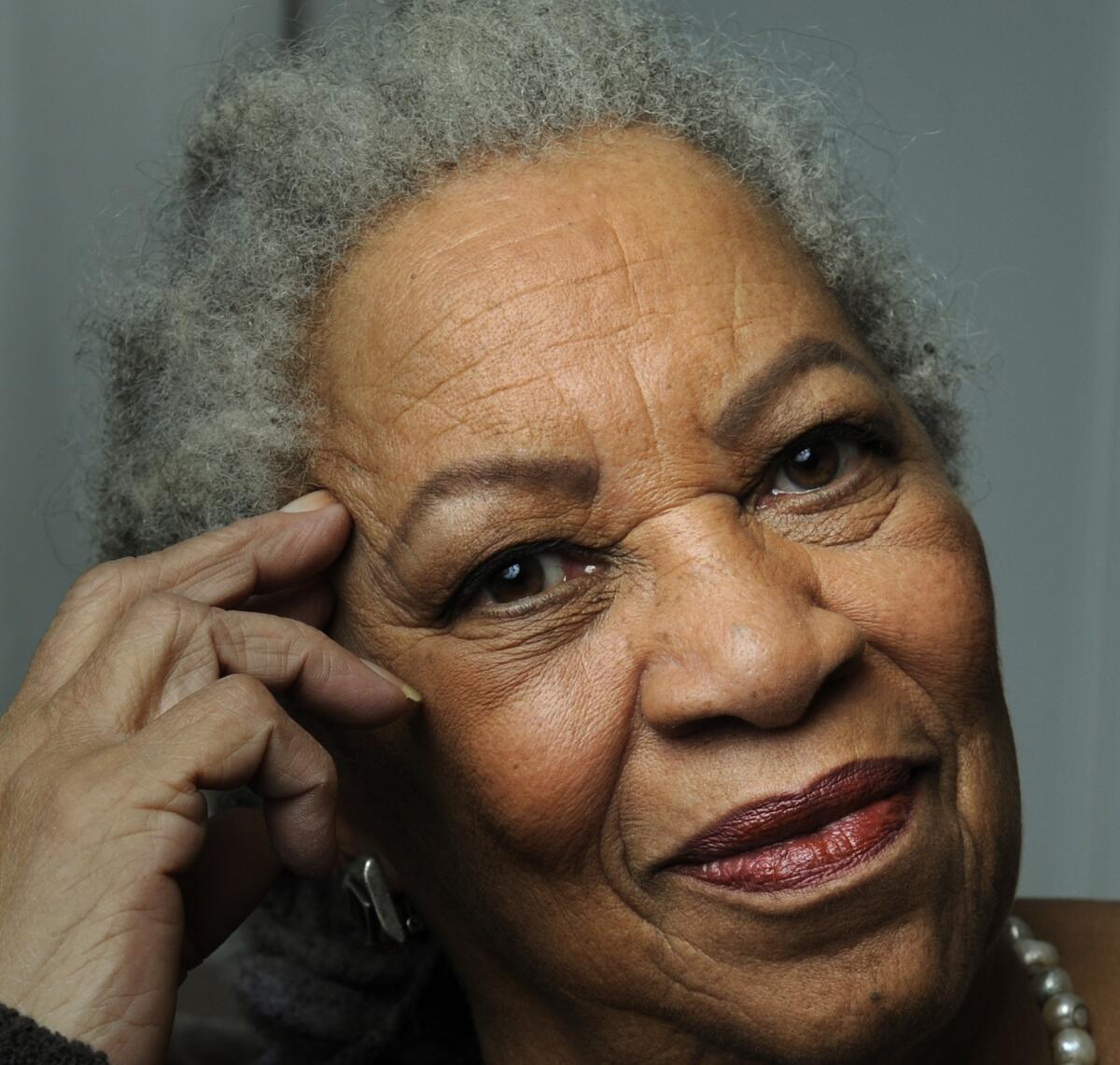

Hearing the news of Morrison’s passing at 88, it’s difficult to imagine what the landscape might have been without her influence. We lost her words yes, the worlds she put on the page, but also her image: She was both a mirror and a map. She reflected our experience back to us and to the world: but also, projected her own.

There was power in the imagery — I was drawn to the 1970s, black and white photographs of Morrison at work. As a very young reader, flipping through a magazine, years away from knowing that I’d even entertain the idea of being a writer, I would catch a glimpse of her with her cloud of an afro, working. Seated in academia — a circle of students before her — her face placid, eyes ablaze, she demanded respect. Other photographs capture her, bent over stacks of paper, passing pencil marks along sentences in manuscripts in a New York City publishing house. Making a way, she cleared space for all of us to follow. It was intentional, every gesture. Her very being and presence was an affirmation and declaration: There is a place for you, but you will have to demand it.

Former President Barack Obama crafted a powerful tribute to late author Toni Morrison, whom he honored with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012.

In the face of vast absence — role models, encouragement, moral support — we make it up as we go. Morrison was a confirmation and embodiment of this. For African American women of my mother’s generation — Morrison’s contemporaries, children of the Depression — this was particularly true. They saw their mother’s and mother’s mothers in her descriptions, the cut of a dress, the contents of a handbag, how the women shielded their hair when the rain began to fall, the quality of their yearning. She wrote these small details into existence, making big but hidden worlds real, word by word by word. When there are no models ahead of you, you are mapping territory for others to follow.

To fill that void, Morrison encouraged would-be writers to take action. Her advice: “If there’s a book you really want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it,” is an oft quoted epigraph and floats in sometimes unattributed memes across the expanse of the internet.

But she embodied this.

Born Chloe Anthony Wofford in Lorain, Ohio, in 1931, she rewrote herself. After receiving her B.A. from Howard University in 1953, she changed her name from Chloe to Toni. Her marriage to Harold Morrison, a Jamaican architect with whom she bore two children, shattered. She took her two boys and circled back home to her parents in Lorain and sorted out a new way, pulled a pencil through those lines. And started anew. She took a job editing textbooks in Syracuse, N.Y. She also landed in a writing workshop where she began building out a short story she’d worked on in college and developed the framework what would become the basis of her first novel, “The Bluest Eye.” In so doing, she unlocked a door within herself: “Writing was ... the most extraordinary way of thinking and feeling. It became the one thing I was doing that I had absolutely no intention of living without.”

While the neighborhood she grew up in was diverse, Morrison reflected in interviews that she often wondered what it would have been like to live in an environment that was predominantly black, close to the family members who would come by bringing their own stories, of victory and heartbreak. She grew up around storytellers and musicians and trained her ear to the twists and turns and language, and directed her focus on neglected communities and obscured histories in a language that was so elegant and alive that it felt participatory.

The publication of “The Bluest Eye” established Morrison as a novelist, but she was also working behind the scenes, by now at Random House in New York City, where she’d taken a senior editor position. She was focused on shepherding black writers, bringing stories into print that might have ended up in slush piles or abandoned after an insensitive or indelicate edit: We have her to thank for carrying into publication the work of Angela Davis, Henry Dumas, Muhammad Ali, Gayl Jones and Toni Cade Bambara.

This effort — this heart work — was insurance that that back and front-lists would include diverse voices. Her lecture published in book form, “Unspeakable Things Unspoken: The Afro-American Presence in American Literature,” explored the construction of literary canons and the need to revise them and be more inclusive. It arrived at the very moment the topic began to gain traction on college campuses across the United States.

Morrison saw very clearly the necessity of a literary landscape that reflects diversity of experience and perspective — it wasn’t an academic exercise, but one that spoke to the life blood of the world we inhabit. But what’s also stitched through her work is how the muting or stifling of these stories and perspectives creates a sense of dislocation — with long-term effects.

In her 1973 novel “Sula,” Morrison addresses her protagonist’s limited options for self-expression, how this was, in certain ways, captivity: “In a way, her strangeness, her naïveté, her craving for the other half of her equation was the consequence of an idle imagination. Had she paints, or clay, or knew the discipline of dance, or strings, had she anything to engage her tremendous curiosity and her gift for metaphor, she might have exchanged the restlessness and preoccupation with whim or an activity that provided her with all she yearned for. And like any artist with no art form, she became dangerous.”

Morrison knew the real danger of being muted, but also of not being fully seen.

Her stories — whether those of celebration or heartbreak — are testimony. They create spaces for the teller and the reader to share and be inspired.

In all the conversations I have had in the hours since I heard the news of her passing, the conversation ends with some version of: “I can’t believe she would leave us now, when so much is in disarray.”

She didn’t leave us with nothing: She left us with a way to look and move and be. She left us with an example of how to exist in the world.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.