Jonathan Lethem revises the Brooklyn of his youth — and his novels

Review

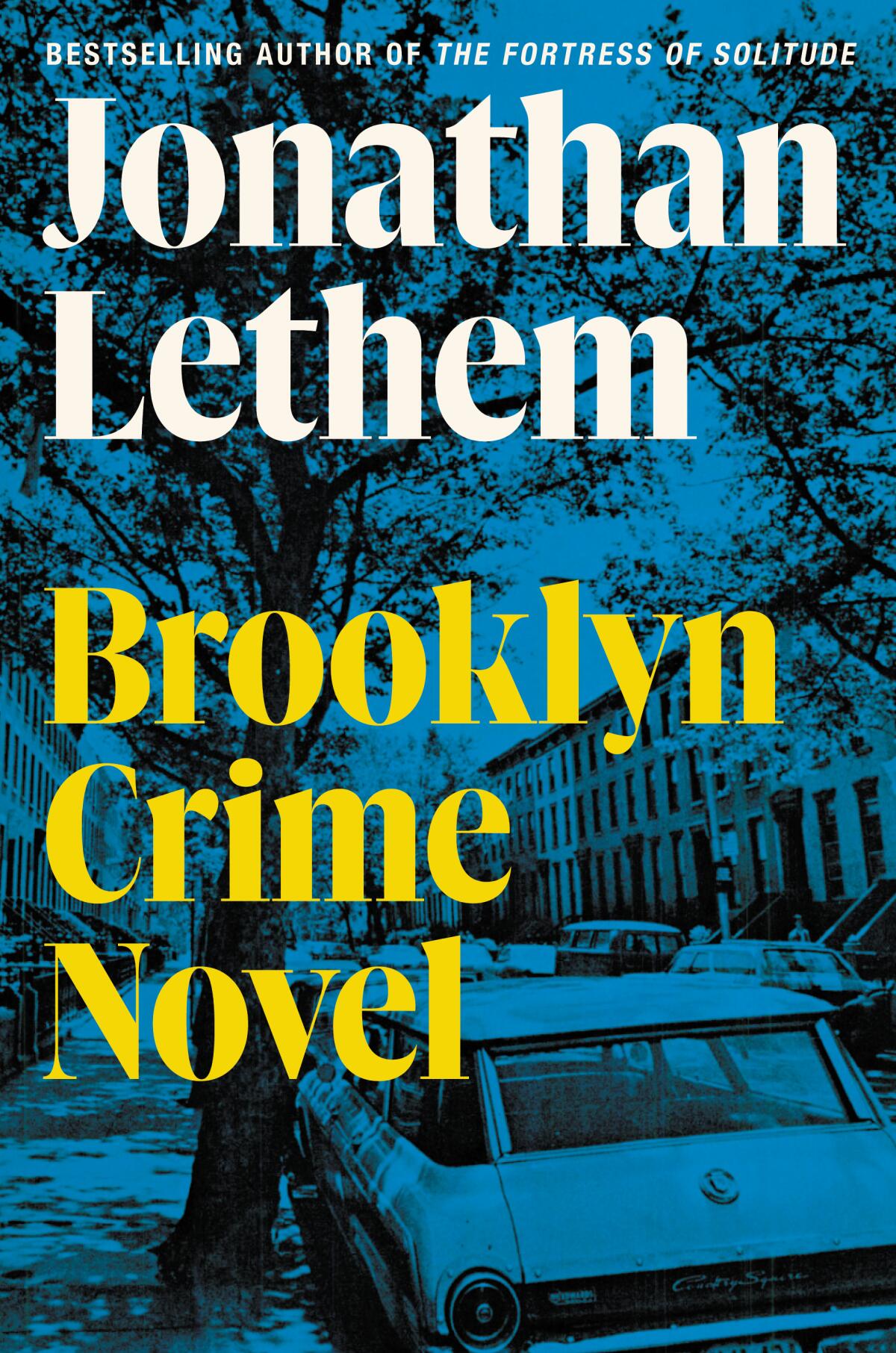

Brooklyn Crime Novel

By Jonathan Lethem

Ecco: 384 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

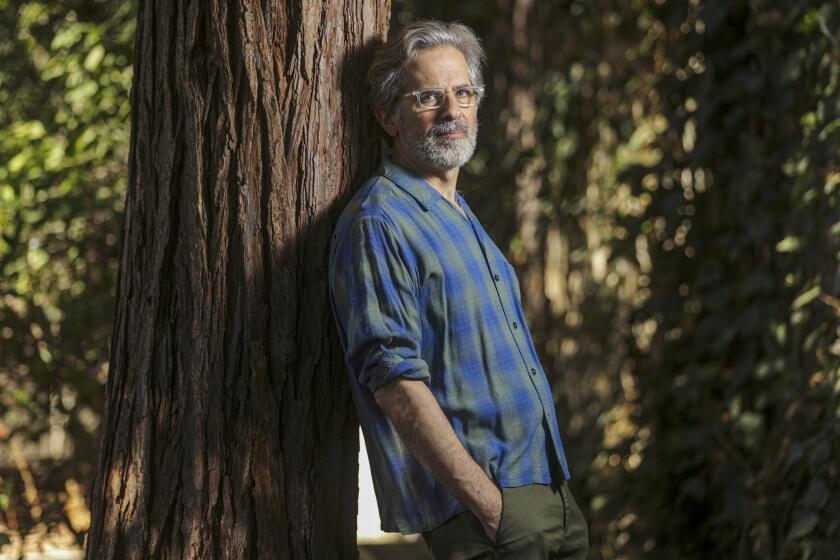

Though the novelist and Pomona College professor Jonathan Lethem has lived in Southern California for more than a dozen years, the Brooklyn neighborhood of Boerum Hill still looms large. It’s been exactly 20 years since Lethem published “The Fortress of Solitude,” a tribute to the Brooklyn of his youth. The landscape has changed considerably: steely grit and urban decay have given way to skyscrapers and endless bistros.

But this transformation was already well underway in 2003, when Lethem published his story of a complicated interracial friendship between two boys who grew up in the pre-gentrified 1970s. What more can be said about it now? According to the author of “Motherless Brooklyn”: a lot.

Lethem’s latest book, “Brooklyn Crime Novel,” explores familiar territory from a new point of view in a style new to him. It unfolds through passages ranging in length from less than a page to a dozen, each labeled and dated. And it leaps between decades and then into liminal spaces that exist across time to cast a light on forgotten exchanges and actions. This kaleidoscopic, fragmentary quality is no lark; it is essential to Lethem’s project.

The novelist perhaps most associated with Brooklyn lives in Claremont and has a delightful new dystopian novel out, “The Arrest”

Abandoning a central hero allows the streets to speak for themselves, with the powerful voice of an omniscient boy of Dean Street serving as interlocutor and guide. This is not to say “Brooklyn Crime Novel” is devoid of characters. Lethem rounds out the book with figures such as C., a young Black boy (circa 1970s) who navigates smoothly among the various kids of the neighborhood regardless of race or background; and the Brazen Head Wheeze, a grizzled barfly and neighborhood institution who takes pleasure in heckling the yuppie-arrivistes 40 years later.

Overwhelmingly, though, Lethem sees the history of the area — the culmination of neglect followed by unchecked gentrification — not through the words of its native children but through their bodies. “They came into consciousness in a distinct time and place,” he writes. “Later they’d find evidence, deep inside their bodies, of how they’d been formed by certain arguments that time and place was having about itself.” These are bodies inscribed by crimes. Lethem seeks to “use what we know to know more than we know.”

At first glance, the book’s stark title — coupled with Lethem’s frequent play with mystery tropes — signals that this is a genre novel. It is definitely not, but the question of crime remains. Dispensing with plot and narrative conventions, Lethem establishes a concrete language to catalog the sweeping range of crimes (or “the dance” as he sometimes refers to them): offenses ranging from muggings, kidnapping and assault to the displacement of working-class residents that accumulate to create a history of Boerum Hill.

This accumulation reaches a climax when the Wheeze confronts a Novelist (who we assume is Lethem) with the retort: “You gentrified gentrification.” No criticism could be more personal or cutting.

As personal a story as “Fortress” was, it was also a fabrication. All these years later, Lethem wants to measure the cost and burden of microaggressions and capital offenses. Realizing one novel could never embody the beauty and tragedy of his home, Lethem uses this one to uncover the slipperiness of the task.

Highland Park has long been the heart of L.A.’s musical bohemia, home to Chicano punk and Billie Eilish. Now, COVID-19 threatens the scene’s very existence.

“Some things, like a gentrification, or a trauma, can’t be so simply placed in time,” he writes. “They exasperate before and after. They dwell instead in a null space, a long between. Distrust anyone who tries to pin them to the pages of a book.” Look, instead, for “what a small number of people remember, even if they avert their eyes when passing on the sidewalk.” The work of uncovering the full truth becomes a life sentence.

It’s a brutal question to ask yourself: Was writing a book about your childhood friends and home turf an act of betrayal? Maybe it was if not everyone managed to survive to tell their stories. Complicating Lethem’s task is that Boerum Hill was contrived in the first place — invented in the 1960s to distinguish its fading brownstones from the surrounding housing projects. Peppering the book with critical observations, the narrator notes, “Generalizations, then, may betray the spirit of our inquiry here. Let’s lay off the romantic flourishes, the rhetoric of memory.” This is no sugar-coated stroll down memory lane.

So yes, he has internalized the hardest knock on “The Fortress of Solitude”: That for all its sharpness and grit, it is ultimately sentimental and thus incomplete. Here, Lethem lets the ragged edges remain visible. The story’s texture and pacing echoes his message. “Brooklyn Crime Novel” is also a product of the 20 years that have passed since “Fortress” — not only in the borough but also in fiction. In the aftermath of autofiction, readers are more comfortable with experimental form and granular, knotted truths.

When “Fortress” came out, Lethem was 39, not yet a decade into his career as a novelist. At 59, he is a MacArthur-anointed “genius” and Pomona’s Roy Edward Disney Professor of Creative Writing. What he has chosen to do now isn’t to capture the moment or stand out in a crowded market, but to write the book that has nagged at him. He’s walking these familiar streets to see beyond the gauze of memory in order to reconcile feelings with facts.

Lili Anolik’s ‘Once Upon a Time ... at Bennington College,’ on the school days of Bret Easton Ellis, Donna Tartt and Jonathan Lethem, concludes this week.

In a recent essay in the New Yorker, Lethem writes about another writer’s attempt to analyze the phenomenon of Boerum Hill, back in 1977: “Jervis Anderson’s gift was to portray the brownstoners as I recall them: people trying, and largely failing, to grasp their place in history in real time. You and I may be doing the same now.”

While “Fortress” is imbued with longing, “Brooklyn Crime Novel” surveys the deep fissures that surface when the pull of home is stronger than nostalgia. He sees himself as an “unwilling” detective, a designated “rememberer.” Ultimately, his is a pursuit with no definite answers, in which the good guys and bad guys sometimes switch roles due to forces beyond their control.

What more is there to say about Brooklyn? Lethem’s revisionist project ultimately unsays as much as it says. “[C]ertain matters fall into wells of silence without necessarily being lies...,” he writes. “The street may seem to swallow knowledge about itself, to render certain things unsayable.” But the novel is also an endless declaration of love. Every neighborhood deserves such a discursive portrait, such ruthless devotion and such an audacious book.

LeBlanc is writer and a board member of the National Book Critics Circle. Her Substack is laurenleblanc.substack.com.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.