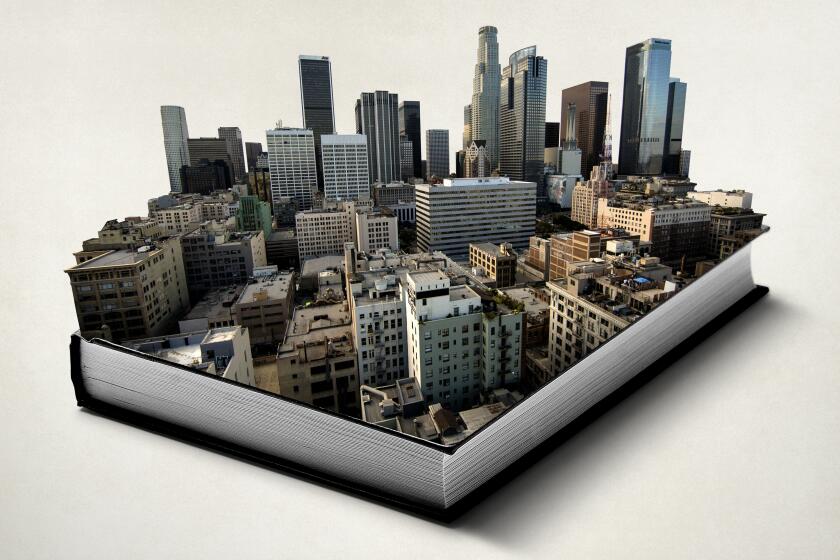

Richard Price returns with a story of urban disaster, grit, hustle and even hope

Book Review

Lazarus Man

By Richard Price

Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 352 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The novelist Richard Price has said that when he sits down to write, he begins with a precipitating event and that “the last thing” that comes to him is the plot. In the case of his gritty and compassionate latest novel, “Lazarus Man” — his first in nearly 10 years — the central incident is the 2008 collapse of a five-story tenement in East Harlem. The disaster kills six and leaves witnesses and survivors in a dense cloud of toxic dust, debris and PTSD.

On the evening before the collapse, 42-year-old Anthony Carter has been killing time drifting from bar to bar, mourning the turn his life has taken and possibly looking for company. Before he quit a cocaine habit six months before, his addiction had cost him his teaching career and his marriage as well as his relationship with his stepdaughter. He licks his wounds in an apartment left to him by his parents, downing shots of vodka to chase his sleeping pills and greeting nightly reruns of “Law & Order” as one might a long lost buddy: “Hello, old friend.”

Before going home that night, Anthony wanders into a makeshift church where Prophetess Irene — “as wide as a bus in a blue-and-white-check pantsuit and matching newsboy cap” — presides over her devoted flock, mic in hand, “booming out her visitations.” In response, Anthony observes, congregants are “upright and juddering like jammed washing machines … roaring, keening, yipping or rolling up and down the aisles like tumbleweeds.” They are all believers, while Anthony is a mildly curious skeptic in need of redemption wherever he can find it. He ultimately exits the service even more unsettled than when he entered.

‘The Tonight Show’ uber host has been off the air longer than he was on it. Does Johnny Carson’s legend live?

Immediately after that scene, Price shifts the focus from Anthony to a peripheral cast of characters, each affected differently by the building’s implosion.

Felix, who is awakened by “a tremendous concussion of sound,” glimpses through his bedroom window “a night-for-day rolling black cloud.” When he realizes what has transpired, the fledgling photographer grabs his Nikon and dashes out to document the scene. Once he confronts the extent of the devastation, though, he’s torn between an instinct to take pictures and a reluctance to seem callous in the face of tragedy.

Mary is a recently separated cop who shares custody of her two kids with her husband. On her nights without them, she trysts with the married colleague she’s been carrying on with for years. Though a good cop, she’s been relegated to the Community Affairs division, where she sees little action but gets a bird’s eye view of the city.

Royal is a funeral director whose business has fallen on hard times. Seeing the disaster victims’ families as potential clients, he dispatches his young son to press business cards into the hands of those watching the rescue efforts.

From “Black Echo” to his latest, “The Waiting,” Michael Connelly’s Harry Bosch books keep taking readers to the dance — partnered with a detective you can’t help but root for, in an L.A. of risks and second chances.

Price grew up in a Bronx housing project near his grandparents. His grandfather was a factory worker from Russia who wrote poetry and regaled the family with stories; his grandmother, Price has said, was “like the Walter Winchell of the windowsill.” Price has clearly inherited their storytelling chops, then fine-tuned those skills by persuading police to let him ride shotgun as research.

He has an ear for streetwise dialogue and an eye for description. He can size up people with a phrase; a doorman is described as projecting “all the warmth of a coal shovel.” Police in the neighborhood have an impossible job, “like pushing a broom without a dustpan.” A chorus of voices enlivens every page in a kind of urban opera.

A little more than 100 pages in, Anthony returns. Thirty-six hours after the building collapse, he is discovered beneath the rubble, semiconscious and unsure why he’s there. His miraculous rise from the ashes is celebrated in the media, and he is suddenly transformed by gratitude.

When a do-gooder ex-con invites him to speak at an anti-violence rally, he finds that inspirational words come easily to him: “Whatever starts out in you as a burden, as an ordeal, in the end, if you persevere, will turn out to be the best thing that can happen to you,” he intones, marveling at his newfound ability to communicate. At the same time, he is suspicious of his own motives, questioning whether he might be a fraud. Some of those around him wonder the same.

Price’s esteemed body of work stretches back decades and includes such classics as “Clockers” and “Lush Life.” His writing for film and television is equally venerated: He collaborated with Martin Scorsese on films such as “The Color of Money” (Price’s screenplay was nominated for an Oscar) and was a writer on the acclaimed series “The Wire.” So it’s no surprise that “Lazarus Man” contains many cinematic moments, even if the plot meanders at times. Toward the story’s end, it regains momentum and cohesion; in one way or another, each of the primary characters finds what they’re looking for.

On Price’s mean streets, parents worry their children will be corrupted by gangs or drugs, or hit by a gunshot meant for someone else. Racism and poverty are facts of life. Everyone’s a hustler.

And yet this is not a cynical novel. As Anthony tells his growing audiences of people just looking for a little reason to hope: “If you have the will to stand fast long enough against the crushing blow, one day you will find that your tables have turned and your heart has healed.”

Leigh Haber is a writer, editor and publishing strategist. She was director of Oprah’s Book Club and books editor for O, the Oprah Magazine.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.