Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

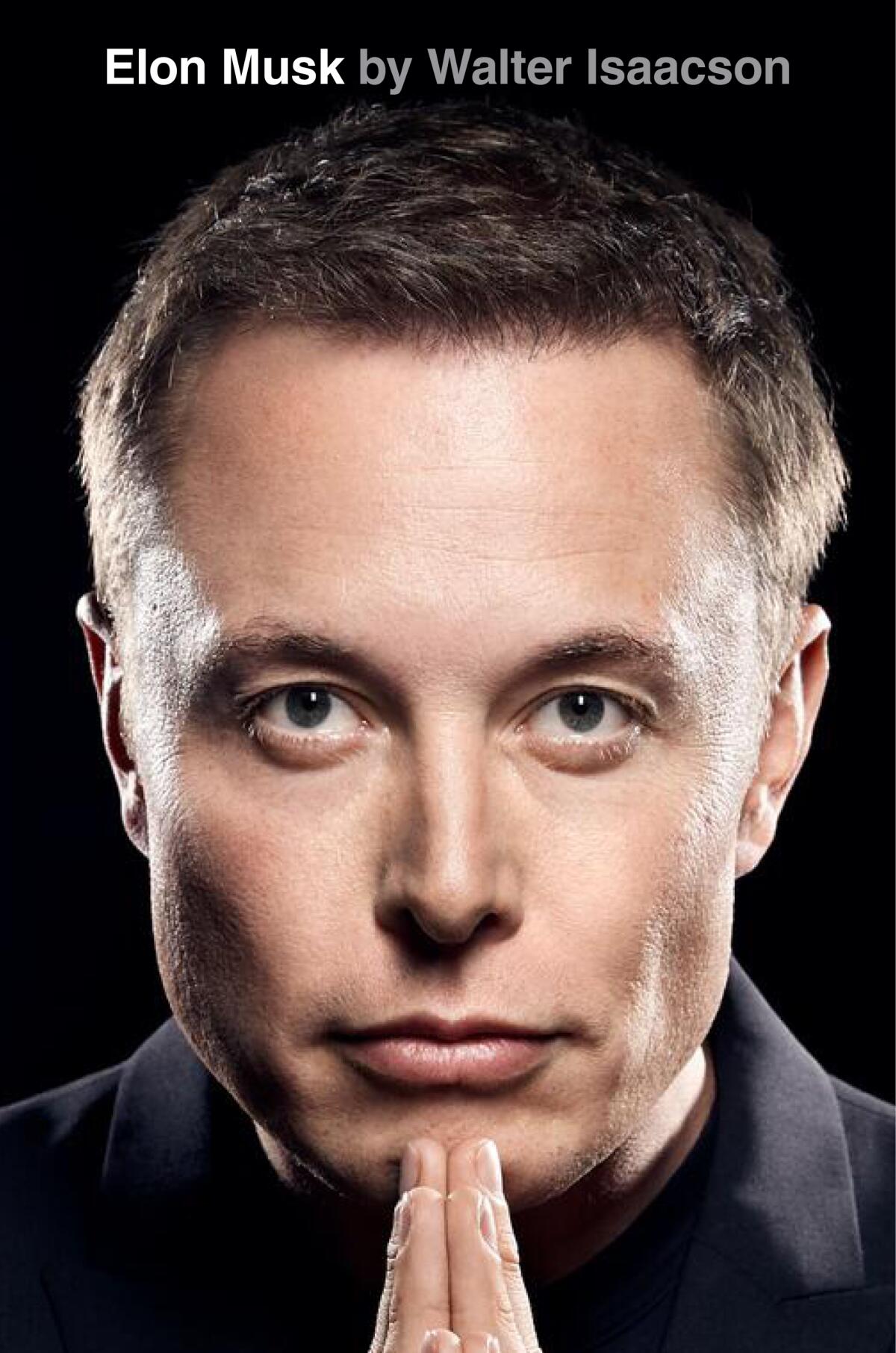

When celebrated biographer Walter Isaacson set out to write about Elon Musk, his subject was not just one of the richest men on the planet but the most polarizing of global billionaires.

How to steer the narrative of a man he considered a visionary but also “crazy at times,” plagued by “manic moods” and self-destructive “demons”?

And how to earn his trust?

“I don’t have an agenda,” said Isaacson, 71, in an interview with The Times. “There’s a large percentage of this country that thinks he’s a villain. They hate him. And there’s, I think, an equally large percentage of people who are wide-eyed fans and think he walks on water.”

When a close friend of Musk’s suggested Isaacson undertake a biography, “I was, like, wow! That would be cool,” he said. “It was at a time when he was bringing us into the era of electric vehicles and becoming Time’s [2021] Person of the Year and making rockets that can land and be reused and was the only person shooting astronauts from the U.S. to space.”

But in a meeting with the tycoon running Tesla and Space X, the author set conditions.

“I said, here’s the two things I’d like,” recalled Isaacson, who has written biographies of Steve Jobs, Henry Kissinger, Jennifer Doudna and Leonardo da Vinci. “One is: I don’t just want a few interviews. I want to spend two years at your side, at all times, at all meetings — nothing excluded, nothing off-limits. And to watch you in action rather than give you a set of questions. Secondly, I want you to have no control over the book.”

And, Isaacson said, “Surprisingly, he agreed.”

The 688-page opus details Musk’s brutal treatment of workers and colleagues, his impulsive business moves and his chaotic romantic life.

Walter Isaacson’s biography of Elon Musk distilled, from fierce mood swings and Ukraine intervention to his ‘dumb’ Pelosi tweet and that time he had the 405 repainted.

But it also delves into how Musk’s abusive father and childhood bullying in South Africa shaped his character. Isaacson writes that Musk’s “reality-distorting willfulness” and his “readiness to run roughshod over naysayers” may be “superpowers that produced his successes along with his flame-outs.”

The ferocious drive of the 52-year-old entrepreneur may not be balanced with empathy for others, Isaacson suggested, but, “As Shakespeare writes, the best are molded out of their faults. So he’s got a lot of faults. To what extent did that mold him?”

Musk gave Isaacson full access to contentious private meetings; encouraged colleagues, family members, ex-wives and girlfriends to speak to him candidly; and, in interviews and 3 a.m. texts, opened up about turmoil in his businesses and his relationships.

It was, the author recalled, “Elon, being up late at night and vomiting because of the stress but also channeling some of the things his father said.”

Controversially, Musk shared — and Isaacson published — encrypted messages with a top Ukrainian official over limits on the Starlink communications satellites that Space X was donating to foil Russian hackers.

The book describes Musk as cutting off Starlink access around Russia-annexed Crimea to stop Ukrainian drones from targeting Russia’s Black Sea fleet. But over the weekend Musk claimed, “At no point did I or anyone at Space X promise coverage over Crimea. Our terms of service clearly prohibit Starlink for offensive military action.” Musk denied Kyiv’s “emergency request” to activate the network in order to avoid “conflict escalation.” Isaacson acknowledged the clarification, but whatever the details, the episode drew new scrutiny of Musk’s foreign policy influence.

Despite Musk’s impetuousness and his open hostility toward journalists, Isaacson said the unpredictable billionaire never backtracked on allowing him unfettered reporting.

“For better and for worse, he has an epic sense of his place and mission in our world, that he’s going to get us to Mars and he’s going to get us sustainable energy,” said Isaacson. “And if you’re that way, you don’t mind having a biographer ride by your side.”

Isaacson’s strategy was to shadow his subject relentlessly. He tailed him along clangorous Tesla assembly lines as Musk micromanaged manufacturing and jetted on a moment’s notice to the hot, dusty town of Boca Chica, Texas, where Space X launched rockets and where Isaacson slept in an Airstream trailer a few hundred yards from Musk’s house.

In April 2022, on the day Twitter’s board accepted Musk’s offer to buy the company, Isaacson assumed a celebration would take place. “But oh no, it was [rush] down to Boca Chica to deal with a methane leak on a Raptor engine,” he said.

“You just always learned to have a very small overnight bag and a couple of changes of shirts,” said Isaacson.

Musk would often lapse into long reflective reveries, and the biographer would learn not to interrupt.

“Sometimes after a meeting, we’d be sitting in the conference room, just the two of us,” Isaacson said. “When he is mentally processing things, he goes silent for two, three, four, five minutes. You are a reporter — imagine restraining yourself from trying to start up the conversation again. [But] that turned out to be a useful approach.”

Also, there is Isaacson’s innate fascination with technology. His father and uncles were electrical engineers, he recounts in his book “The Innovators,” a survey of digital pioneers, and he grew up as an “electronics geek.” At Harvard, he majored in history and literature, but he also learned programming.

Isaacson spent years as a journalist, rising to editor of Time magazine and, after a stint at CNN, heading the Aspen Institute. But he looks back to his childhood in New Orleans, where he now teaches history at Tulane, and recalls, “We had a workshop. We fixed cars. We fixed TV sets. We made ham radios together.”

In hours spent with Musk in engineering meetings or on factory floors, Isaacson said, “I was genuinely curious about, ‘OK, stainless steel for the axial skeleton of the Cybertruck? How are you going to make the chassis?’ These were questions I asked. … A key to the story is understanding how caring about assembly lines, valves and chassis is important to the successes he has had.”

Musk emigrated from South Africa to Canada at 17 and then to the U.S., where, after college, he made millions from his involvement and part ownership in PayPal. He had homes in Silicon Valley, where he ran Tesla, and in Los Angeles, where he built Space X.

Musk has fathered 11 children with three women, including musician Grimes, sharing custody and even bringing his toddler, X, to work with him at Space X. Nothing has hurt Musk more, Isaacson said, than the loss of his first-born to sudden infant death syndrome and the estrangement from his transgender daughter Jenna after he said she embraced Marxism.

In his ‘Elon Musk’ biography, Walter Isaacson examines the billionaire’s political evolution, from fundraising for Democrats to trolling progressive politicians.

Musk has said he has Asperger’s, a form of autism, and that “gives him a very analytical engineering mind-set,” said Isaacson. “Autism manifests itself in a thousand ways in different people. But it means he doesn’t have good receptors for other people’s emotions, nor does he have a craving to make people like him.”

The book describes Musk’s obsessions with science fiction, with violent video games, with establishing a “multiplanetary civilization” and with founding colonies on Mars via Space X rockets.

Is the Mars fixation crazy? Isaacson isn’t sure: “The people who are crazy enough to think they can do that may be the ones who do.”

Nonetheless, Isaacson shakes his head recalling how Musk relished his weekly “Mars Colonizer” meetings. “They’d spend an hour, sometimes two hours, and they’d talk about, What would the cities look like on Mars? What would people wear? What would the robots do? How would they govern themselves? What form of decision-making would they use? I’m going, whoa! I’d have to pinch myself.”

Isaacson acknowledges he is “not a big fan” of Musk’s Twitter purchase: “Enabling extremists to blather on conspiracy theories on Twitter turns me off.”

Call it the ‘Isaacson Accord’: the agreement behind Walter Isaacson biographies, including ‘Elon Musk,’ to leave the assumption of difficult genius untouched.

But he also allows, “It probably wasn’t bad to open the aperture to more debate on some of these topics.” And he contends that despite Musk’s attacks on “woke-mind virus,” he doesn’t have “just have one set of politics. He’s not always pushing views on the far right or far left. There are times when he’s very moderate. So, like in everything, he’s mercurial.”

In the final analysis, Isaacson considers Musk to be “one of the three great innovators of our time.”

“Steve Jobs brings us into the era of the digital revolution with human-friendly computers and a thousand songs in our pocket, and smartphones. Jennifer Doudna brings us into the era of life sciences by showing us how to edit our DNA. And Musk is bringing us into a future of electric vehicles and space adventures — as well as blowing a few things up, including Twitter.

“But they’re each people who, 50 years from now, you’ll look back and say they’ve touched the surface of history and you can still feel the ripples.”

What: Bestselling author Walter Isaacson joins the L.A. Times Book Club to discuss “Elon Musk” with Times columnist Anita Chabria.

When: 2 p.m. Pacific Oct. 1

Where: The El Segundo Performing Arts Center. Get tickets on Eventbrite.

Join: Sign up for the Book Club newsletter for the latest books, news and live events.

Do you enjoy our book conversations? Here’s how to support the Los Angeles Times Community Fund and the newspaper’s literary and literacy programs.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.