“That ugly, generic building,” Rick Castro says, pointing out the window of a car parked on Santa Monica Boulevard just west of La Brea Avenue. Castro is in his mid-60s, a soft-spoken man with long black hair and an all-black wardrobe. He’s gesturing north, to where a primary-colored glass-and-concrete apartment complex has risen from the asphalt. “In 1990, this used to be a Carl’s Jr. This is where I photographed Zack.”

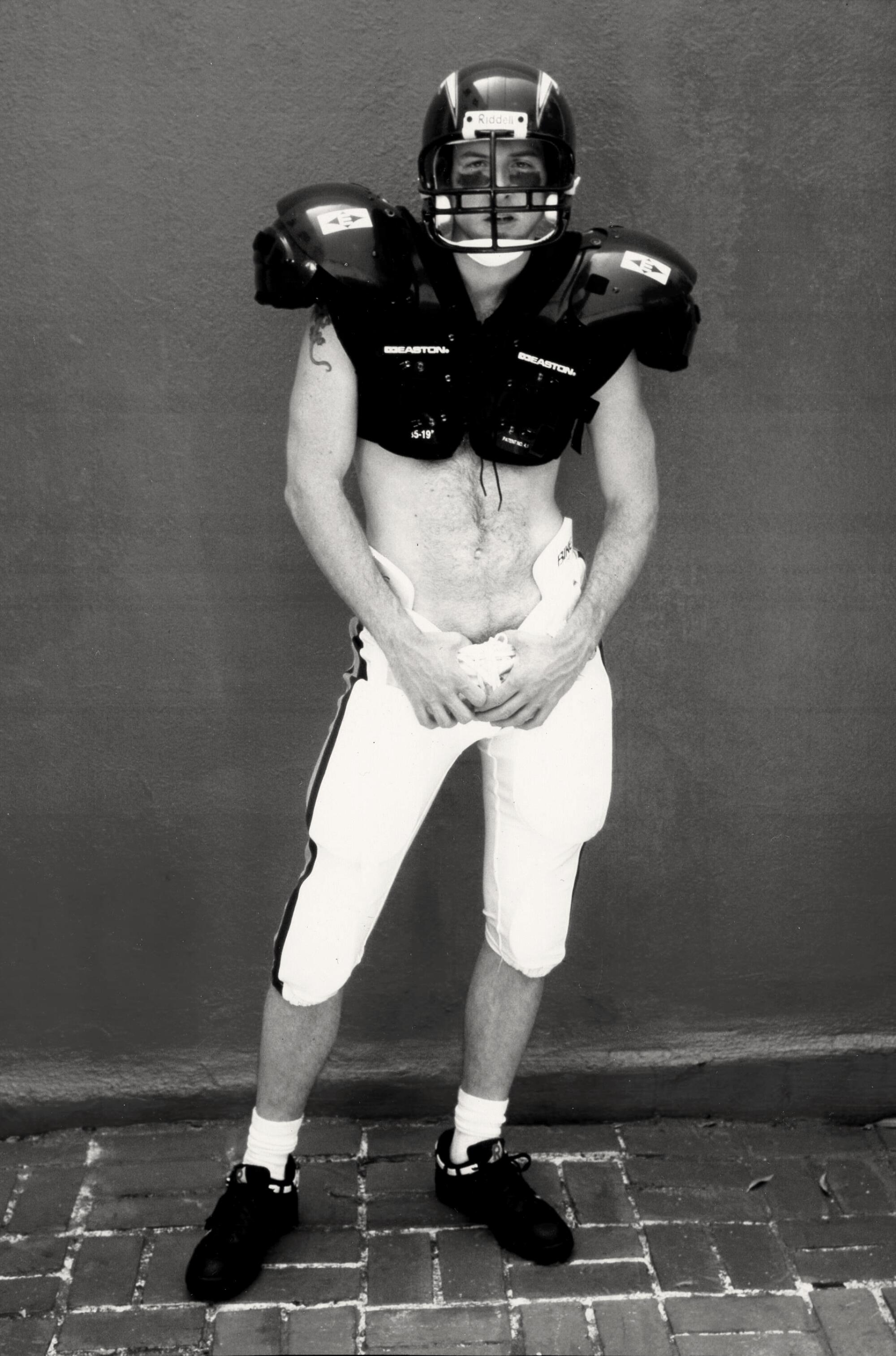

Castro flips open “S/M Blvd,” a new book that features a collection of his photographs of male hustlers, and finds Zack’s image. “So, I’m eating my usual chicken club sandwich, parked in their parking lot,” he remembers. “And out walks Zack. Now, he had his pants on, but he pretty much looked like this. He was 6 foot 2. The mirrored sunglasses. So hot. I leaned out my window and I said, ‘Dude, you want to model for me?’ And he goes, ‘Sure.’”

Melanie Nissen was there at the creation of L.A. punk and has the pictures to prove it. She talks about “Hard+Fast,” a new collection of her photos.

On the page, it’s 1990 again. Zack’s in profile; his arms are crossed in front of his chest, and his jeans and underwear are pulled down around the tops of his thighs. He’s wearing a cowboy hat and smirking at the camera, and he is blond and young and incandescently sexy.

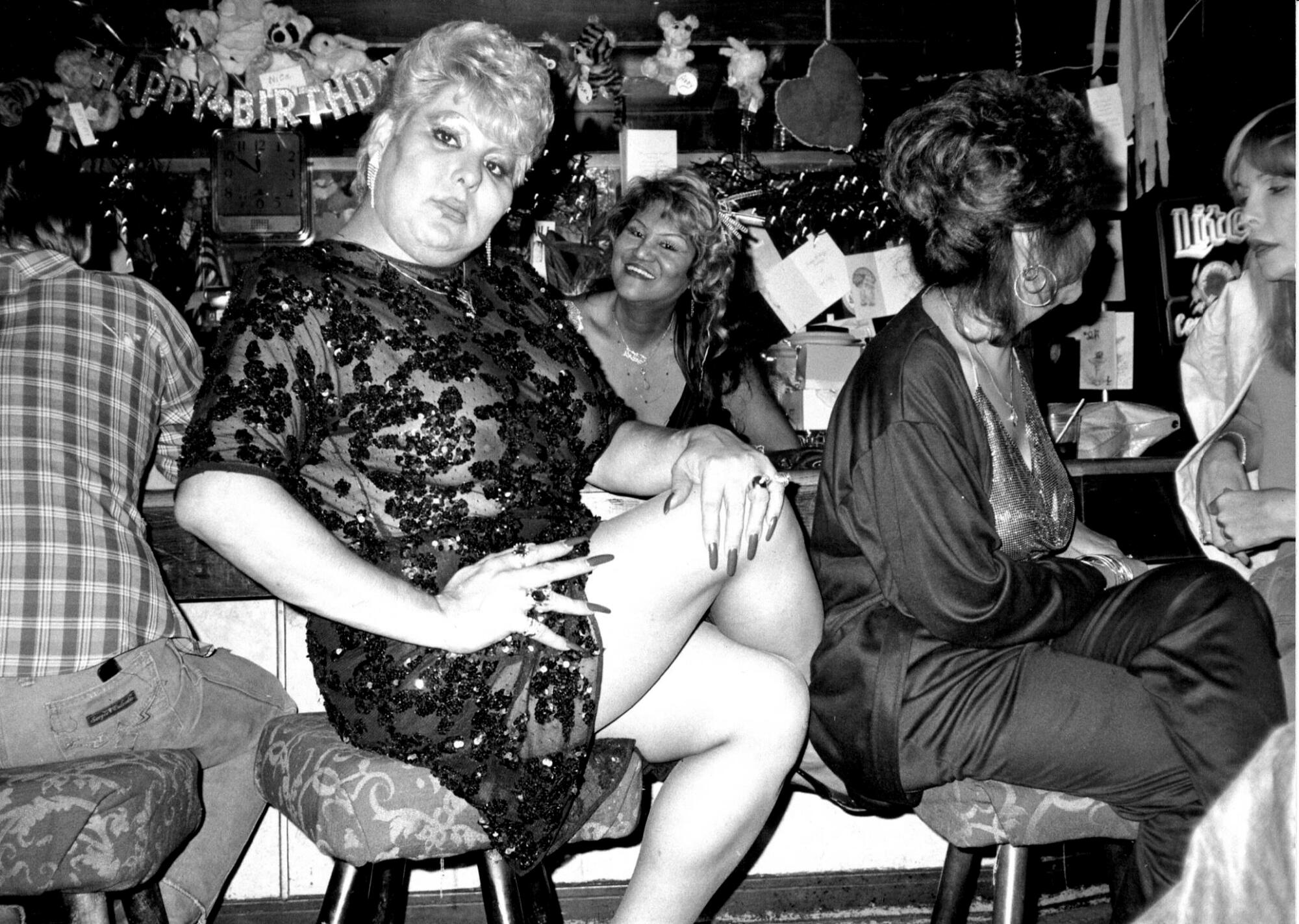

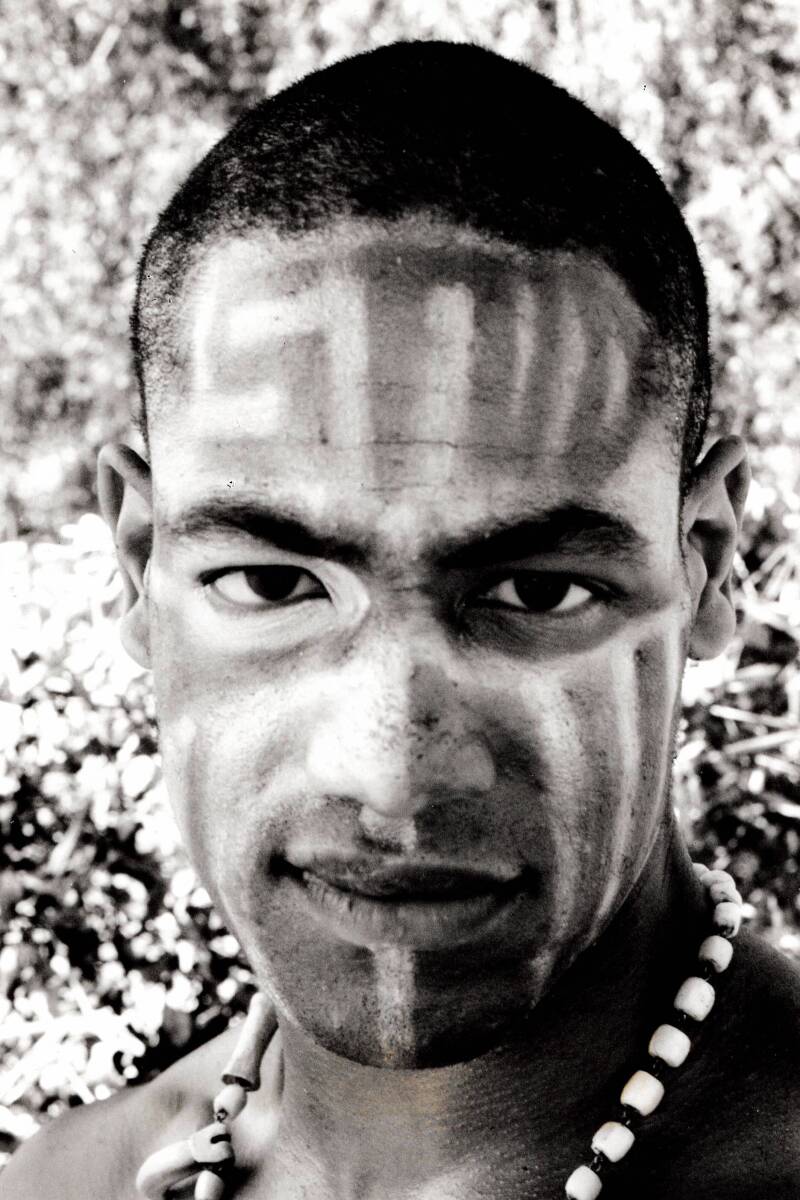

This story is a representative one. Castro met most of the men featured in “S/M Blvd” in a similar fashion: while he was hanging out, and they were looking for work. At the time, Castro says, the Hollywood stretch of Santa Monica Boulevard was a veritable buffet of male sex workers. Their unofficial territory ran from Van Ness to La Brea avenues, and the corners they worked were segregated by race and sometimes gender — the trans sex workers tended to congregate together, he says, and the boys got whiter the farther west you went.

At the time, Castro was a freelancer, doing wardrobe on photo shoots. He’d only recently started taking pictures, and he was happy to turn his lens on anything that caught his eye. L.A.’s hustlers became a regular subject.

“When I wasn’t working, I had a lot of time on my hands,” he says. “I was so obsessed, so fixated, that I would spend every day going up and down the Boulevard in my ’67 Mercury Cougar.”

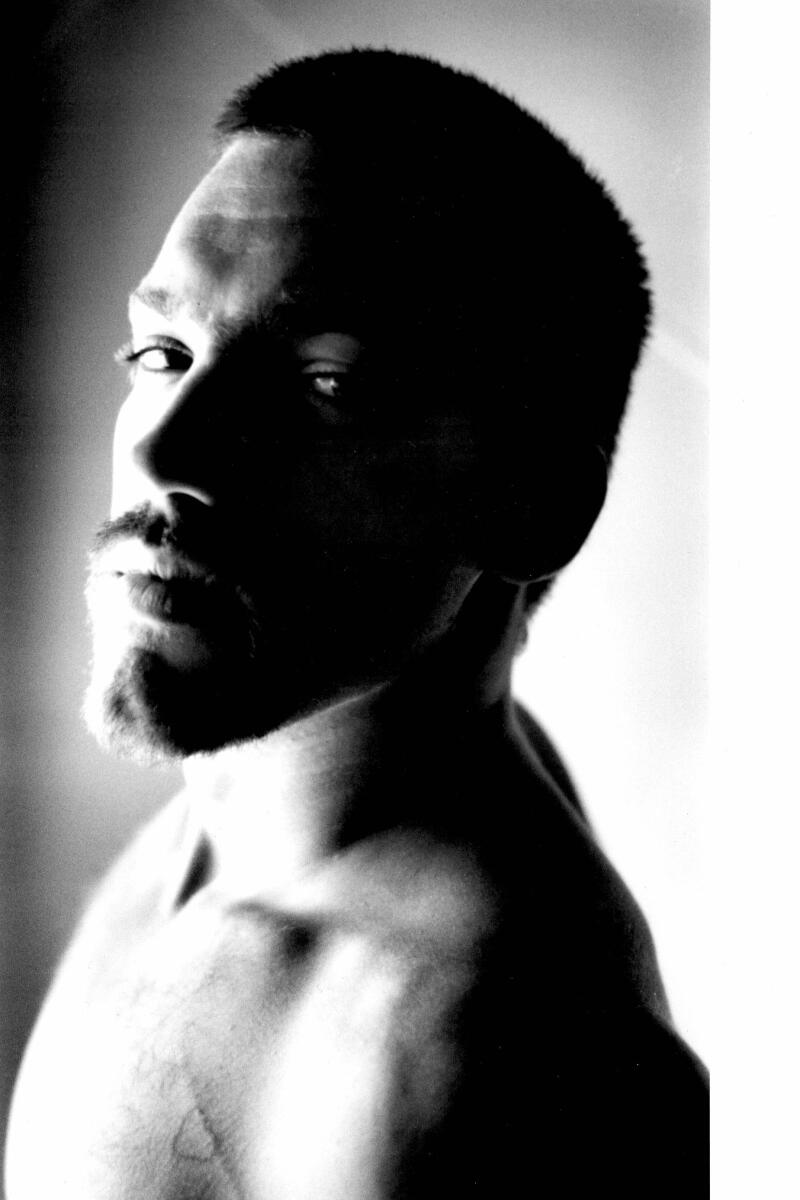

If he thought someone would look good on film, he would ask them to come back to his West Hollywood apartment, where he’d painted the walls black, red and silver in order to provide dramatic backdrops for his images.

Castro’s photographs of queer life in Los Angeles, which focus on subcultures and kink scenes — particularly BDSM and leather — would eventually end up at the Getty, the Kinsey Institute and the Tom of Finland archive, among other collections. But these hustler portraits were never part of his public archive — until now.

“S/M Boulevard” is a collaboration with All Night Menu, a micropress run by writer and editor Sam Sweet. Sweet found out about Castro’s hustler portraits by accident, he says. He was interviewing Castro for a different project when he noticed a portrait on the wall: a man clad only in jeans and boots, posing with a cigar and a beer bottle.

“[Castro is] really well known for explicit nude homoerotic imagery,” Sweet says. “So I was struck by this image of a man who wasn’t nude. It was a really timeless, iconic image.”

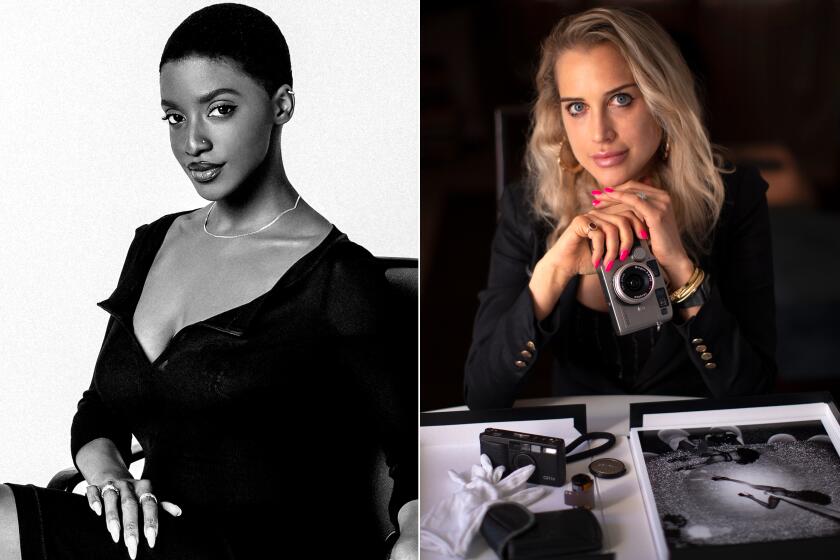

Photographers Adrienne Raquel and Elizabeth Waterman interrogate each other about strip clubs, regional variations and the power of Black beauty.

“I’ve always been interested in the hustler culture of L. A., and there’s so little photo documentation of it,” Sweet adds. “I’m interested in that process of revisiting the archive of a well-known photographer, but recontextualizing part of the work so it tells a story that people didn’t know was there.”

He also liked the idea of desegregating queer history.

“Rather than so-called queer stories being only told to a queer audience, it becomes an L.A. story,” he says. “And then that queer history becomes relevant to anyone who has an interest in Los Angeles history or the history of place in general.”

When he met Castro, Sweet had already been talking with the city of West Hollywood about making something for its annual book fair; ultimately, he secured a grant that would cover most of the cost of this book’s initial print run.

Castro has watched with amazement as the broader culture has caught up to his work, which was once considered taboo. Early on, he recalls, “I had an agent, a wardrobe person. I was working for Drummer magazine, which was a leather magazine, and a couple of others, like Bound and Gagged. And she’d say, ‘Ricky, do not use your real name when you publish these pictures.’ And I go, ‘Why not?’ She goes, ‘It’ll end your career.’”

‘The Mic,’ a fledgling open-mic night for queer poets and performers, has found an incongruous — but in fact ideal — home at Micky’s nightclub.

It’s taken a while, but “2023 has been a really good year for me,” Castro says. ”All of a sudden I’m mainstream. ... I was part of a collective in front of City Hall earlier this year. It took all this time for there to be acceptance and interest in what I’ve been doing since the very beginning, which is documenting queer culture full-on: no censorship, no apologies.”

The street-hustling culture documented in “S/M Blvd” is long gone. By the end of the ’90s it had all but disappeared, due in part to construction along Santa Monica Boulevard, which replaced old streetcar tracks with medians.

“There was nowhere to stand, because it was all ditches,” Castro says. “There was no place to park. And no one could pull over anywhere.”

But another, more totalizing force was making itself known at the same time: the internet. Suddenly, you didn’t even have to leave your home — or risk getting hassled by the police — to see beautiful boys plying their wares.

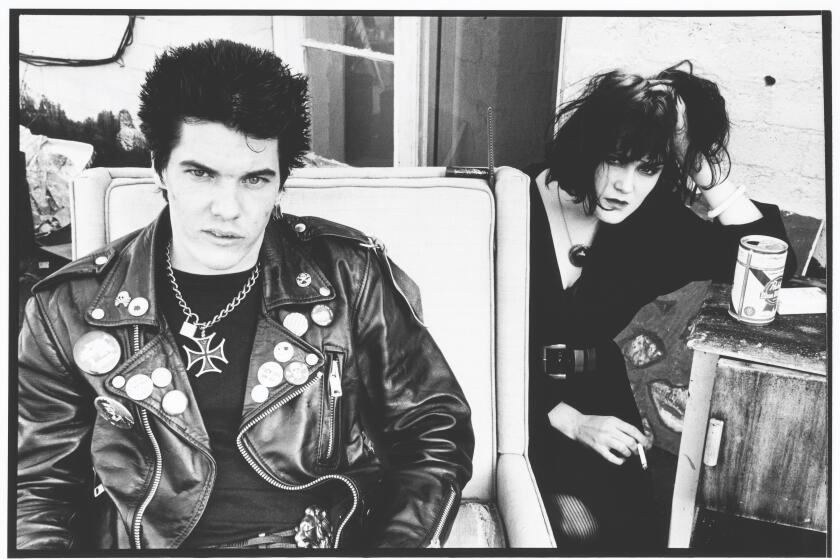

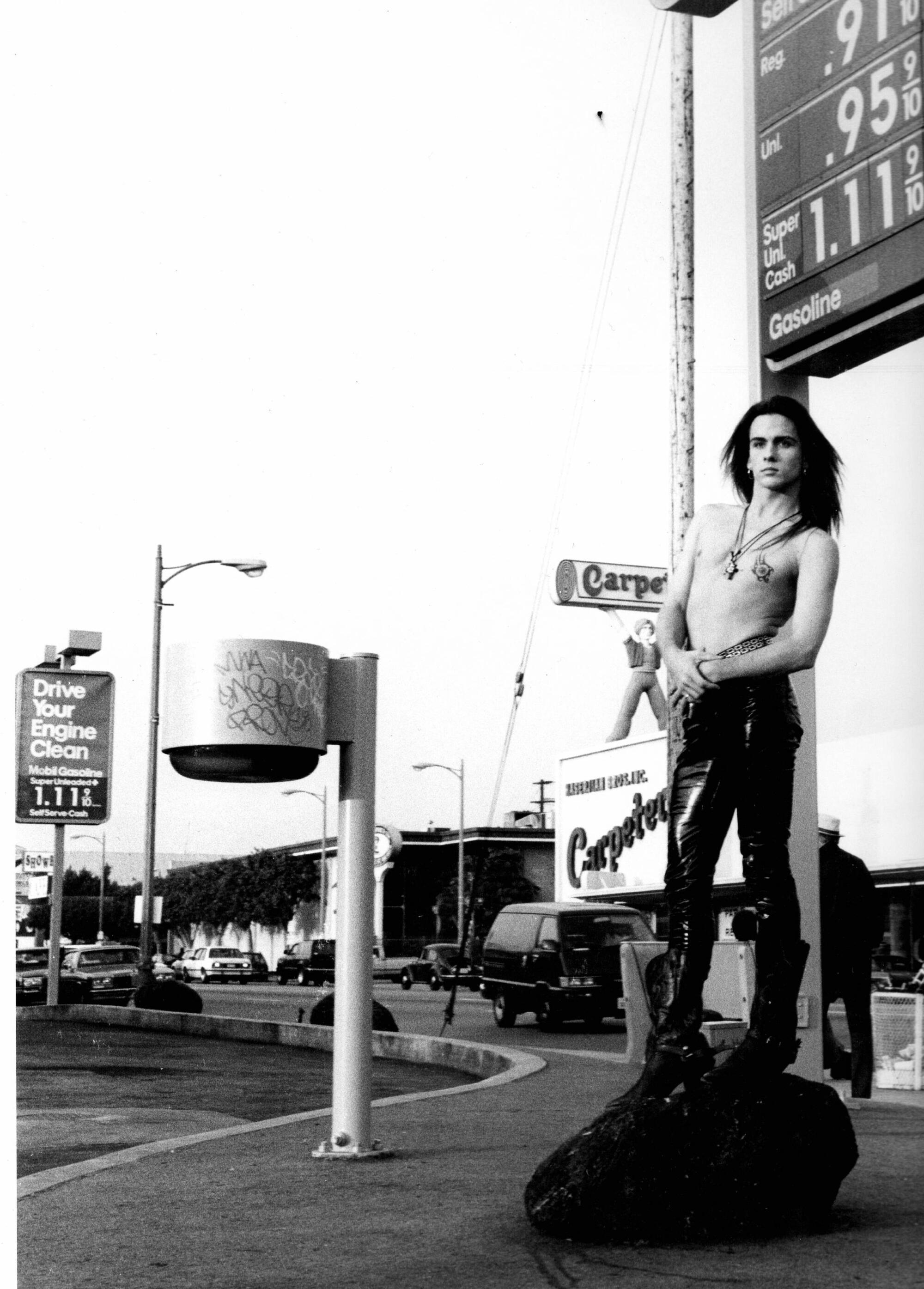

1

2

1. A hustler who called himself “Savage!”, 1988. 2. Josh, 1993. (Rick Castro, courtesy of All Night Menu Books)

“S/M Boulevard” is a nostalgic work, and that’s intentional, Castro says.

“What I could write [about the hustler scene], what we could make films about,” he says, “it’s more romantic than the reality of what it was. It looked ugly; it was a hard life, sad life. But you could romanticize it and make it beautiful.”

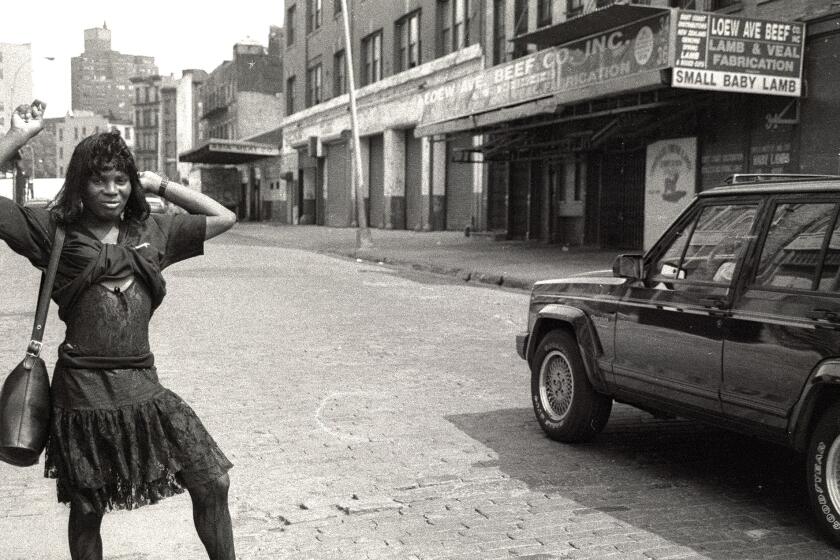

‘The Stroll,’ premiering Wednesday on HBO and Max, is part of a wave of recent films to reconstruct LGBTQ+ stories from unexpected sources.

Los Angeles is a hard city to get to know; on the surface, it’s all flat, empty streets and too-bright sunshine. So much of the city’s intrigue comes from learning to see its layers: the glamour underneath the grime, the dull apartment building that used to be a Carl’s Jr. where you could meet a gorgeous blond and take him home for the afternoon. Castro sees his work in part as a record of the city’s hauntings.

Driving along Santa Monica now conjures plenty of ghosts. Castro pauses at the intersection of Highland Avenue, where a bright pink Trejo’s Coffee and Donuts now occupies the corner. A line snakes out the door: Angelenos picking up breakfast before work. From here, Castro points to a patch of lawn across the street, out in front of a Public Storage building, where he says hustlers would nap between jobs.

“I can see them, you know,” Castro says. “I can still remember when I was driving up and down, there was a hustler boy, and he had lit his T-shirt on fire. No one stopped. No cops, no fire department. It just burned. And he was there for a while, and then he walked away. I remember that vividly etched in my mind.”

Those acts are etched onto the city too, he believes, their mark just as indelible.

“But other places are successful and people like —” he turns to Trejo’s. “Look at here, how there was a line for these stupid little doughnuts. Not that great of a location, but there’s an energy.”

Romanoff is a writer and the author of several novels for young adults.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.