The back-and-forth over ‘The Blind Side’ misses the big picture. So did Michael Lewis

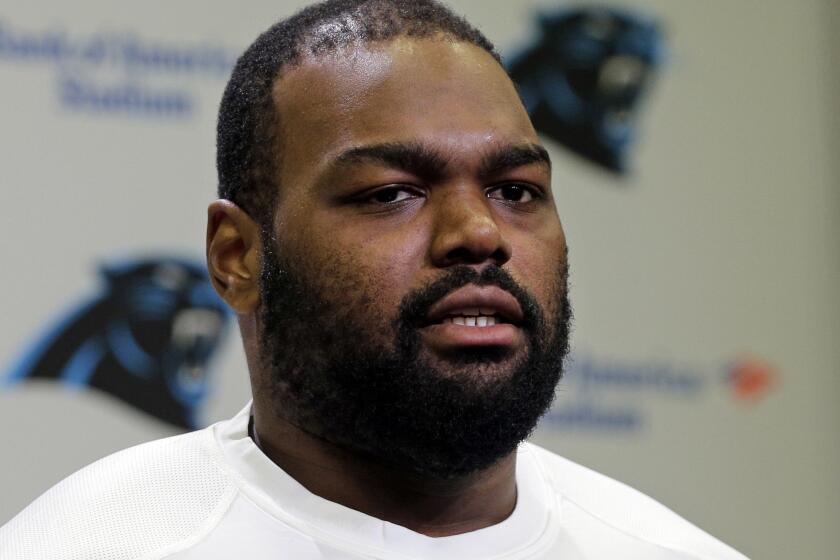

In 2006, Michael Lewis wrote an enthralling bestseller, “The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game,” in which he related the story of Michael Oher, an athletically gifted Black teenager who grew up in poverty before being adopted by a wealthy white family who helped guide his path to NFL stardom.

The book became the basis of an even more popular film that won Sandra Bullock an Oscar for her portrayal of Leigh Anne Touhy, Oher’s fiercely protective adoptive mother.

A few days ago, Oher filed a legal petition claiming that this story is a sham — that the Touhys never adopted him, and instead made hugely profitable business deals in his name after placing him under a conservatorship. (The Touhys have disputed this last claim. They now reportedly plan to end the conservatorship altogether.)

I wish I could say that I was shocked.

The saga of Michael Oher, as told by Lewis, always read like a fantasia, one intended to put the gloss of white saviorhood on a set of events that smacked of racial exploitation.

In light of NFL veteran Michael Oher’s allegation that the heroes of ‘The Blind Side’ exploited him, Steve Almond’s review of the 2006 Michael Lewis book resonates.

As I wrote in a review for this newspaper at the time, “The essential message of his book is that poor black children matter, are worth saving, not because of the content of their characters or minds, but because of their physical prowess. Like most fans — myself included — Lewis prefers not to notice the prejudices that belie our lust for sport, the perverse arrangement by which watching young black men engaged in violent spectacle has become our most profitable form of entertainment.”

The most astonishing aspect of the Oher story is that virtually no one who read the book, or saw the movie, chose to recognize this perversity. Or rather, it was briefly acknowledged by Lewis and his subjects — and then totally disregarded.

Lewis writes: “[Oher] didn’t go so far as to treat Leigh Anne with suspicion but, as Leigh Anne put it, ‘With me and Sean I can see him thinking, If they found me lying in a gutter and I was going to be flipping burgers at McDonald’s, would they really have had an interest in me?’”

Nobody in “The Blind Side” ever answers this question, though its implications are obvious. Oher worries the Touhys have ulterior motives; he doesn’t entirely trust them.

So put yourself in Michael Oher’s shoes. Having already endured a movie that you felt portrayed you in a poor light, how would you then feel if you discovered that the story of this benevolent white family adopting you — a story whose conversion into film generated hundreds of millions of dollars — was a lie?

Michael Oher, the NFL star whose life story was dramatized in Oscar-winning film ‘The Blind Side,’ alleges the Tuohy family tricked him into a conservatorship.

According to Oher, the Touhys convinced him to sign a document at age 18 that recognized no familial relationship yet granted them the legal power to make decisions about his financial affairs, despite the fact that he was an adult with no physical or psychological disabilities.

The Tuohys claim that they had no ill intentions and never made much profit; their attorney responded aggressively. Among those who spoke in their defense Wednesday was Lewis. In one interview, he told the Washington Post, “They showered [Oher] with resources and love. That he’s suspicious of them is breathtaking. The state of mind one has to be in to do that — I feel sad for him.”

I have no idea what the outcome of Oher’s legal petition will be. That isn’t really the point.

Because “The Blind Side,” to me, was never just a book about Oher and the Touhys. It was about an entire cultural and economic industry, what I would later deem the Football Industrial Complex, which acts to harvest young men — mostly young men of color — from this country’s impoverished precincts.

Because of their physical gifts, they are recruited by private high schools and colleges, segregated from the general population and exploited for their extraordinarily profitable talents.

Promoting football as a form of empowerment based on the saga of a single NFL player is like presenting the lottery as a social program based on the story of a single Powerball winner.

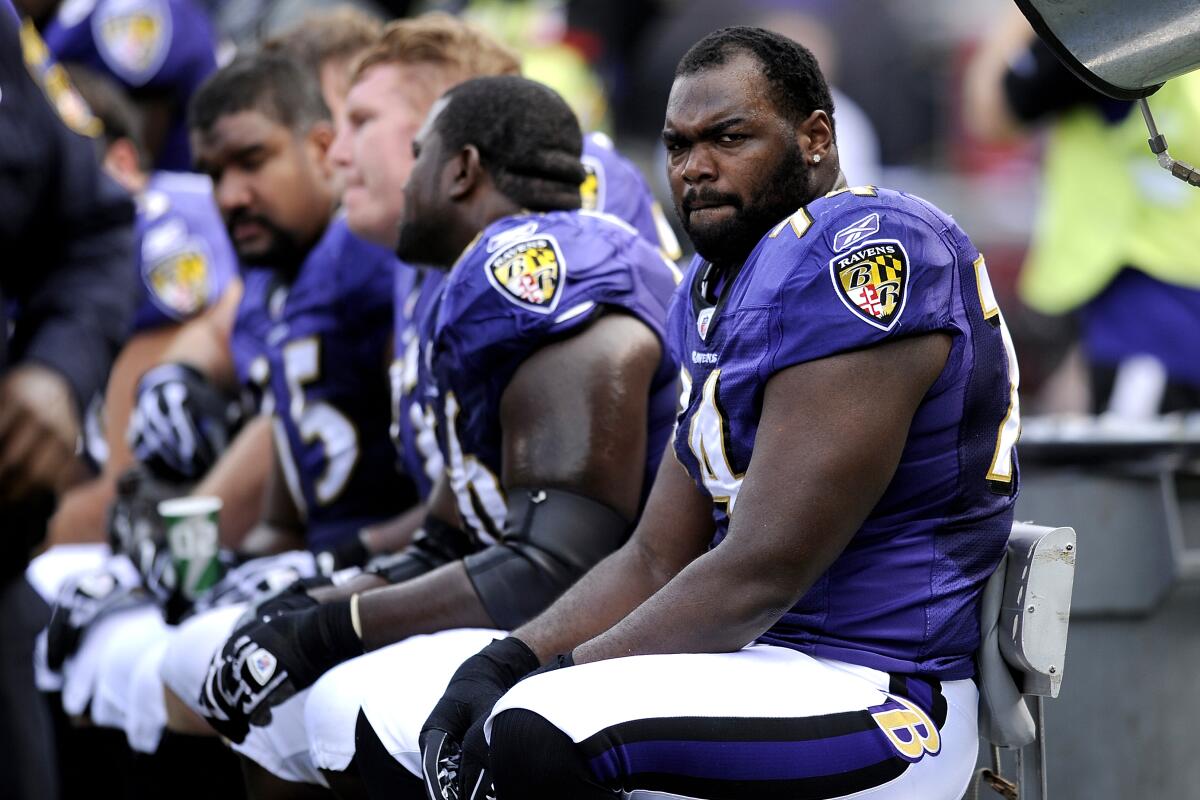

That’s precisely what happened to Michael Oher. The Touhys helped him game the educational system so that he could remain in high school, then convinced him to attend their alma mater, Ole Miss. He was eventually drafted in the first round by the Baltimore Ravens.

Lewis chronicles all this as if it were a heroic journey. It does not appear to trouble him that, for every Michael Oher, there are tens of thousands of African American children who will never be rescued, who are born into broken family systems, crumbling schools and underserved neighborhoods.

What these children need isn’t the charity of some wealthy family or the stern wisdom of some sanctified coach. They need the kind of social, economic and educational support that can begin to repair the damage wrought by two centuries of systemic racism and economic injustice.

Promoting football as a form of empowerment based on the saga of a single NFL player is like presenting the lottery as a social program based on the story of a single Powerball winner.

It’s true that players choose to compete and, at the highest levels, receive huge salaries. But the power dynamics remain eerily familiar: A predominantly Black workforce generates huge revenues first for universities and then for wealthy white team “owners.” Pro players risk grievous injury. Nearly a third of them will suffer brain damage, according to the NFL’s own actuaries. The average length of a player’s career is barely three seasons. The odds that a high school player will ever play professionally is approximately 1 in 1,300.

A few years ago, I began to feel guilty about watching football.

Michael Lewis surely understands the cynicism of the Football Industrial Complex. But for all his talents in describing large systems, he’s not very interested in their morality, the way they affect people. Instead, he cleaves to a narrative formula, in which he lionizes the plucky outsiders who outsmart the establishment. In “Moneyball,” he celebrated Billy Beane and the Oakland A’s for revolutionizing Major League Baseball via statistical analysis. In “The Big Short,” he glorified short-sellers as a corrective for Wall Street’s precarious housing market.

In both cases, he elided inconvenient facts and oversimplified complex systems. In “The Blind Side,” he portrayed his friends, Sean and Leigh Anne Touhy, as selfless benefactors and the NFL as a heroic destination.

Lewis is, by any standard, a first-class storyteller, that rare example of a journalist talented enough to be a perennial bestseller. But it sometimes feels like his approach to journalism sacrifices nuance, even empathy, in service of a rollicking tale. Years after he first struck gold, many journalists are reexamining how systemic injustices affect both groups and individuals. It is ironic that Lewis, who perfected the blend of analysis and anecdote, seems so often to leave out the reality on the ground.

The Writer’s Life: Michael Lewis puts faces on business stories

I’m thinking here of the way Lewis described his forthcoming book, “Going Infinite,” about Sam Bankman-Fried, the head of the FTX cryptocurrency exchange. Speaking at a bitcoin conference in May, Lewis expressed a curious glee at the collapse of FTX and the subsequent indictment of his central character, Bankman-Fried.

“I thought, ‘I don’t have a book,’” he observed. “I had this conversation with a kind of person I used as a sounding board … and he said, ‘Your problem is you don’t have a third act. You have the first two acts, but you don’t have a third act.‘ And I said, ‘That’s absolutely right; I don’t know how to end it.‘ A week later, FTX blows up. I was so grateful.”

I understand what Lewis means of course. That hunger for great material is what makes his work exceptional and often illuminating. But his readiness to look past the human impact of the FTX collapse filled me with a different kind of empathy. I felt kind of sad for him.

Almond is the author of “Against Football: One Fan’s Reluctant Manifesto” and other books.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.