‘I didn’t want a white savior’: How a debut novelist scrambled the racial narrative

On the Shelf

Wade in the Water

By Nyani Nkrumah

Amistad: 320 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Mr. McCabe, the older blind man down the street, is wise and loving and always makes the time. Nate, who owns the fried chicken joint, is generous and willing to lend an ear. Fats and Cammy are faithful friends. There are plenty of kind souls in Ella’s Black community in Ricksville, Miss., but life still brims with anguish for this precocious 11-year-old who is just starting to see the world, circa 1982, with clearer eyes.

Ella, the third of four children, is the only one among them with a different father, the product of an affair her mother had while Leroy was away. While her siblings are light, Ella is as dark as any African — a reminder of her mother’s shame. Ma is cold toward her; Leroy, well, he’s much worse.

Ella narrates much of the action in Nyani Nkrumah’s powerful debut novel, “Wade in the Water.” But some chapters tell the story of Kate, a white girl growing up in Philadelphia, Miss., in the 1950s and ‘60s. Her father infects her with ideas that are vile even by the standards of that time and place. A violent KKK member, he helps mastermind the infamous murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner. (The father is a fictional creation.)

Kate grows into Katherine, a Northern liberal intellectual who thinks she has moved beyond her past, until a research trip to Ricksville, where she befriends Ella, shows how shallowly she had buried her father’s influence. As the book progresses, she comes to feel like both a real person and a metaphor for America. She wants to be better but is unwilling to do the real work of self-reflection, and the consequences of her blindness are devastating. As Ella turns to Katherine as a potential hero, tensions between her would-be savior and her suspicious Black neighbors come to a boil.

‘Decent People,’ De’Shawn Charles Winslow’s propulsive second novel, concerns a triple homicide in a seemingly sleepy segregated Southern town.

Nkrumah was born in Boston but spent most of her childhood in Ghana and Zimbabwe before returning to the U.S. for college, majoring in biology and Black studies at Amherst. She spoke recently by video from her home in Maryland about racism on two continents and the dreaded white-savior narrative. Our interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Mr. McCabe teaches Ella how differently she’d be perceived in countries like Ghana. How much did your childhood in Africa shape you?

In Ghana there were no color dimensions. My parents mixed with a lot of expatriates, and I went to an international school and didn’t know anything about color or race. When I came back to the States for one year around age 7 there was some racism — there was an incident where someone chased us and threw rocks at us, but my sister beat them up, so I mostly forgot about it.

Then when I was 15, there was a famine in Ghana and my dad, who was a pediatrician, got a job in Zimbabwe. That began a whole new era in my life. We moved there in 1983 and they were just beginning to dismantle their system of apartheid. It was a pivotal moment in the country and I was caught in the middle of it. I was the first Black girl, with just two Black boys, in an all-white class and I really felt the world had gone mad. It was so traumatic — nobody would talk to you, nobody would sit with you.

Was colorism an issue in the Black community in Zimbabwe?

A lot of what I know about colorism I learned here. For the book I talked to my friends here and read about the roots of colorism stemming from slavery, with the whitening of the Black population. But in Zimbabwe we did have the divisions too. It was very confusing for me because my family is all across the board — none of us are the same color.

Mr. McCabe tells Ella, “slave owners changed our eyes, but we let them.” He’s indicting the Black community for absorbing the bias toward dark skin. How do you think Black readers will respond to that viewpoint?

That’s a tricky one. I look forward to seeing the reviews. Colorism is definitely part of slavery’s legacy, but to some extent you have to decide if you’re going to carry forth those negative legacies into the future. The question is, can we discuss it more and change things? It’s not a criticism, it’s just a point for reflection.

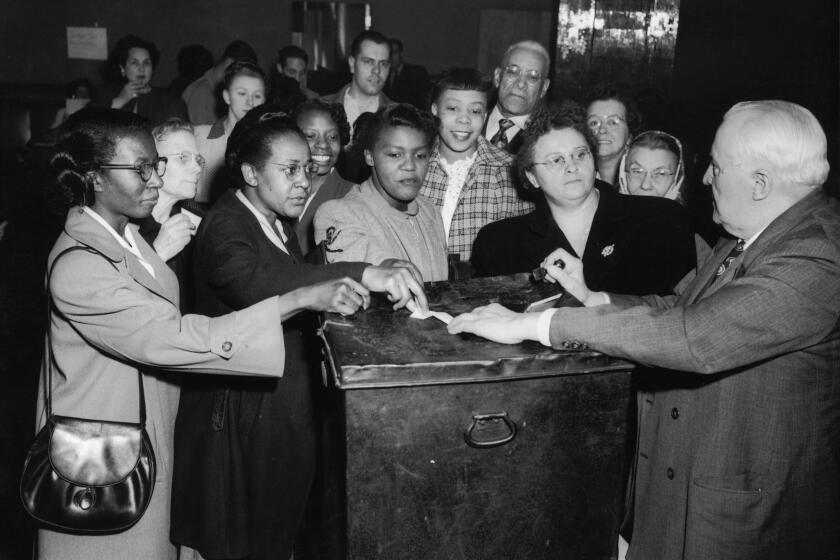

Remember the names Fannie Lou Hamer, Constance Baker Motley and Mary McLeod Bethune. Vice President Kamala Harris does, as does historian Martha S. Jones.

Katherine’s struggle seems to mirror white America’s blind spot — that unwillingness to frankly examine our past. Did you intend it that way?

No, it just came from the writing of the character. Some early readers said, “We don’t quite get Katherine’s character. She appears out of the blue,” which she did in that draft. So I had to think about where she came from and the issues she encountered and what drove her and how she tries to escape the family history.

Overcoming racism is a struggle for her. You wonder, How on earth does she get past this legacy that she’s trying to shed? Some of it seeps through but not all of it. To what extent can you escape?

She never really deals with the lingering echoes of her father’s racism.

That’s very true. I hope that came across. Yes, she wants to change, but the lies we tell ourselves are the problem. She doesn’t see things the way readers see her. Her warm feelings for Ella are real but she has this other part of her that keeps interfering. She’s one of these in-between people.

I used to belong to a book club and we used to dissect books and pull them apart, and I thought this would be a good opportunity for people to build bridges and have an open dialogue. I wasn’t thinking about a metaphor for America, but I do hope the reader engages in these pivotal issues.

NoViolet Bulawayo recalls rejoicing when Zimbabwe’s dictator was deposed — and then tackling its slide back into tyranny with the novel “Glory.”

Ella learns about the danger of investing in a white savior, but she still emerges with a hopeful world view.

I didn’t want stereotypes. There are excellent novels that I love, like “The Help” and “The Secret Life of Bees,” that have a different dynamic. I didn’t want a warm Black mama or a white savior. Those pitfalls I deliberately tried to avoid, and I wanted to lift up Black men so I had two powerful Black male characters. And I wanted to make it less obvious about color — so we do have ‘good’ people across the board. The more hopeful message at the end is more aspirational. It’s not how we see the world today.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.