How a Zimbabwean Californian came to write a modern, African ‘Animal Farm’

On the Shelf

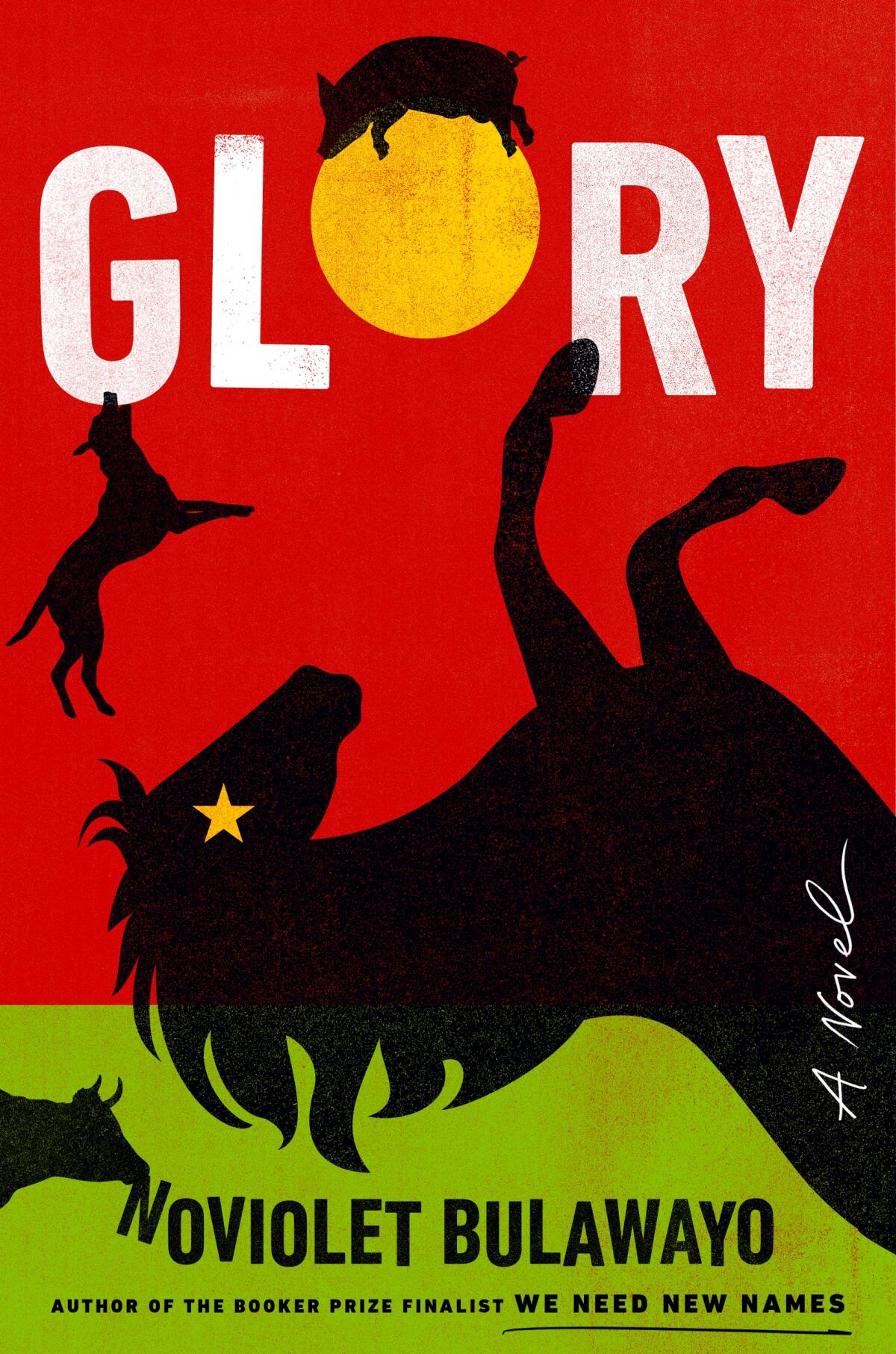

Glory

By NoViolet Bulawayo

Viking: 416 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

On Nov. 14, 2017, novelist NoViolet Bulawayo woke up to the news that Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s ruler for nearly four decades, had been deposed in a coup. Bulawayo, 40, was at home in Oakland, where she lives while teaching at Stanford.

“There was a sense of shock and disbelief because he had seemed so untouchable for the longest time,” she recalls over a recent Zoom call from her “first home” in Zimbabwe. “There was so much celebration, just the joy of seeing the dictatorship come to an end the way it did. It was complicated, though, because we knew his deputy was going to take over. But we hoped against hope that we had turned a corner.”

Back in California, Bulawayo began making plans to return to Zimbabwe and see for herself what was happening “on the ground.” Perhaps she could write a nonfiction book about this moment “too unbelievable to ignore”? Her first novel, “We Need New Names,” had been an overwhelming success, winner of the 2013 L.A. Times Book Prize for first fiction and shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Told in the spirited voice of a 10-year-old girl named Darling, it had provided an utterly fresh perspective on life in Zimbabwe.

But that was nothing compared to Bulawayo’s new novel, “Glory,” a rollicking animal allegory that took form only after she went back to Zimbabwe in 2018. Immersing herself in the rituals of local life, she spent her time “just observing people in every moment.” She waited on endless gas lines, traveled across the border for groceries, watched in horror as the first post-Mugabe elections turned violent. “The sense of hope turned very quickly into disappointment and devastation,” she says with a sigh.

As the country’s mood shifted, so did her idea for the book: Why not write a modern-day parable of Zimbabwe through the eyes of farm animals? (George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” happened to be trending on social media at the time.) Tapping into an ancient storytelling tradition, she realized, would also allow her to write with greater distance.

“Of course, in our folklore there’s so much use of animals,” Bulawayo says. But it was also uniquely suited to her project. “The choice gave me a sense of freedom that I don’t think would’ve been possible otherwise.”

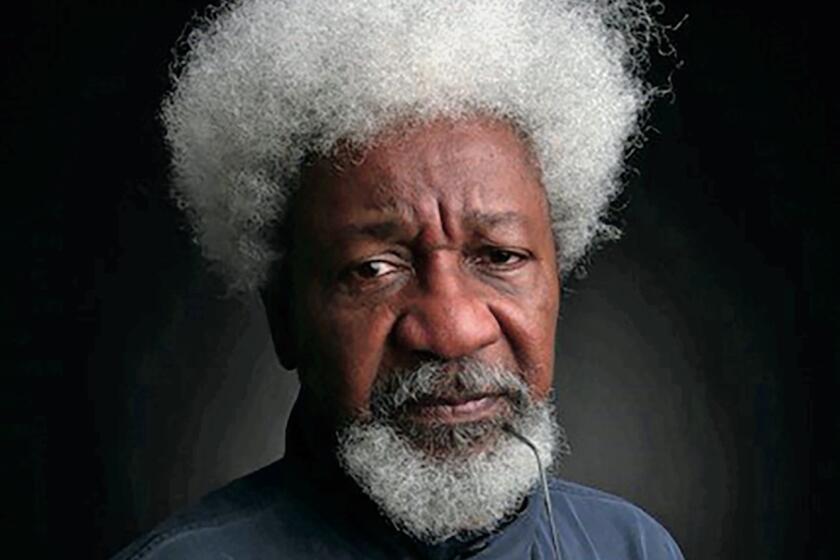

The Nigerian writer, the first sub-Saharan winner of the Nobel Prize, discusses ‘Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth.’

Suddenly, her book came to exuberant life. Set in the fictionalized country of Jidada, “Glory” is a brash and boisterous take on Zimbabwe’s political life. The aged, entrenched “Father of the Nation” is a horse; the country’s most popular evangelist is a pig; the military police are ferocious attack dogs. (The U.S. president appears as a “Tweeting Baboon.”) Destiny, a goat who has returned to the township of Lozikeyi after a 10-year exile, serves as the emotional heart of the book.

“Our stories kind of intersect in a way,” Bulawayo says of her goat-avatar. “The experience of being disconnected from your country and then going back to confront past ghosts.” Bulawayo left Zimbabwe after high school in 1999 and didn’t return until 2013. “We all have stories and selves that we leave behind, many of them not reconciled. And, for me, coming back in that moment of change, that moment of possibility, also included sitting with my own personal ghosts and by extension the country’s ghosts.”

Destiny wrestles heroically with some of her country’s most painful “ghosts.” Having left after being tortured during the 2008 elections, she returns to discover an even darker episode her mother endured in 1983. That piece of real-life national history — the Gukurahundi massacre around the city of Bulawayo — survives in her mother’s memory but is exorcised only after Destiny “breaks the silence” and writes it down.

“When you think about narratives of trauma, and especially the case of the Gukurahundi, people don’t forget their dead. Their names live on,” Bulawayo says. “Writing, which is a form of storytelling, is really very central in not only bringing to life the unspeakable and helping people heal their trauma, but also holding governments accountable. Because once our stories are public, we have to deal with the conversations that are hopefully going to come about.”

Bulawayo, who adopted her name in tribute to her hometown (“More than the country itself, I think it’s the place that haunted me in my long absence,” she says), is part of a group of Zimbabwean authors who are opening up those new conversations. She feels a kinship with writers such as Tsitsi Dangarembga, Petina Gappah, Novuyo Rosa Tshuma and Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu, among others. “I’m really delighted,” she says, “to be writing along with a cohort of writers and artists who are very dedicated to telling difficult stories.”

Ndlovu, author of ‘The Theory of Flight” and “The History of Man,” agrees. “This is a great time to be a Zimbabwean writer not only because there are so many of us writing,” Ndlovu says, “but because all of us are writing about the country, its history, present and future from many different vantage points, which means we can actually be in conversation through our work and learn from each other.”

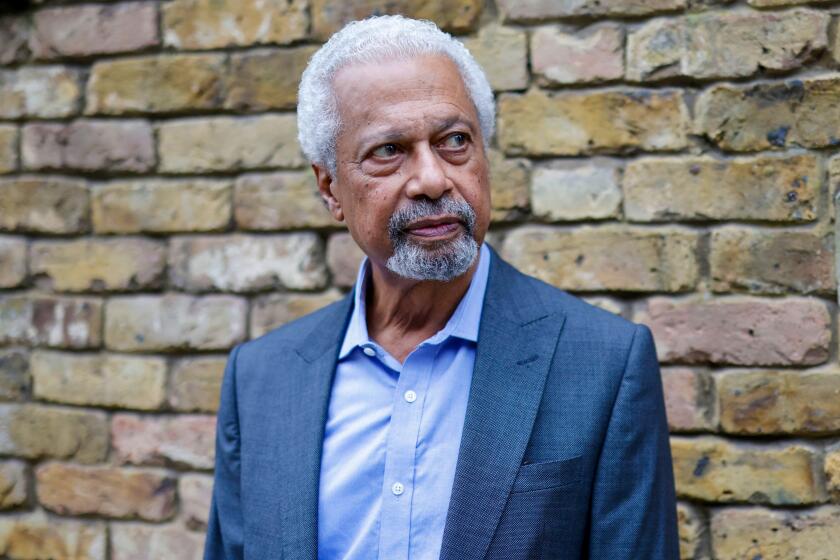

Much of the world may consider him obscure, but to generations of writers with African roots, Abdulrazak Gurnah is both an influence and a role model.

Tshuma, author of “The House of Stone,” adds that she feels a connection to Bulawayo’s work “not merely because it’s Zimbabwean, but because it touches me and stimulates me and has important things to say about the human experience.” Tshuma praises Bulawayo’s ability to find a “subversive and creative, heartbreaking and funny” way to tell a story that transcends national borders.

This was always Bulawayo’s intention. “As much as Zimbabwe was the inspiration,” the author explains, “I was trying to speak to the larger story, because tyranny is not only a Zimbabwean story. We even saw it try to rear its head in the United States. And I think the view of animals helped to achieve that. It was important for me to speak to the moment when so many countries are going through upheaval and tumult.”

In the end, the book offers a somewhat rose-colored vision of the future. The “Old Horse” is overthrown; his vice president, just as venal and brutal, is also swept away. The people of Lozikeyi, galvanized by Destiny’s truth-telling, come together to neutralize the rabid dogs. “In the end, the glory rises for the people and there’s a sense that this is a lasting glory,” Bulawayo says, “mostly because the citizens have decided to become authors of their destiny.”

This is not just the optimism of parable. Bulawayo remains bullish on Zimbabwe and her own role in it. She believes writers play a key part in issuing the wake-up call to “take back our lives.” Ndlovu, for one, echoes her sentiments. “I think from the moment Dambudzo Marechera wrote ‘The House of Hunger’ on the eve of the country’s independence, writers have always played an important role in the future of the country,” Ndlovu argues. “Zimbabwe’s writers have a history of challenging, critiquing and jettisoning dominant narratives, and that is what has always made me hopeful for the country and the future.”

Bulawayo has reason to be encouraged. After all, look at Mugabe. “There was a time when we all thought he was not going anywhere,” she says, “but he fell.”

Tepper has written for the New York Times Book Review, Vanity Fair and Air Mail, among other places.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.