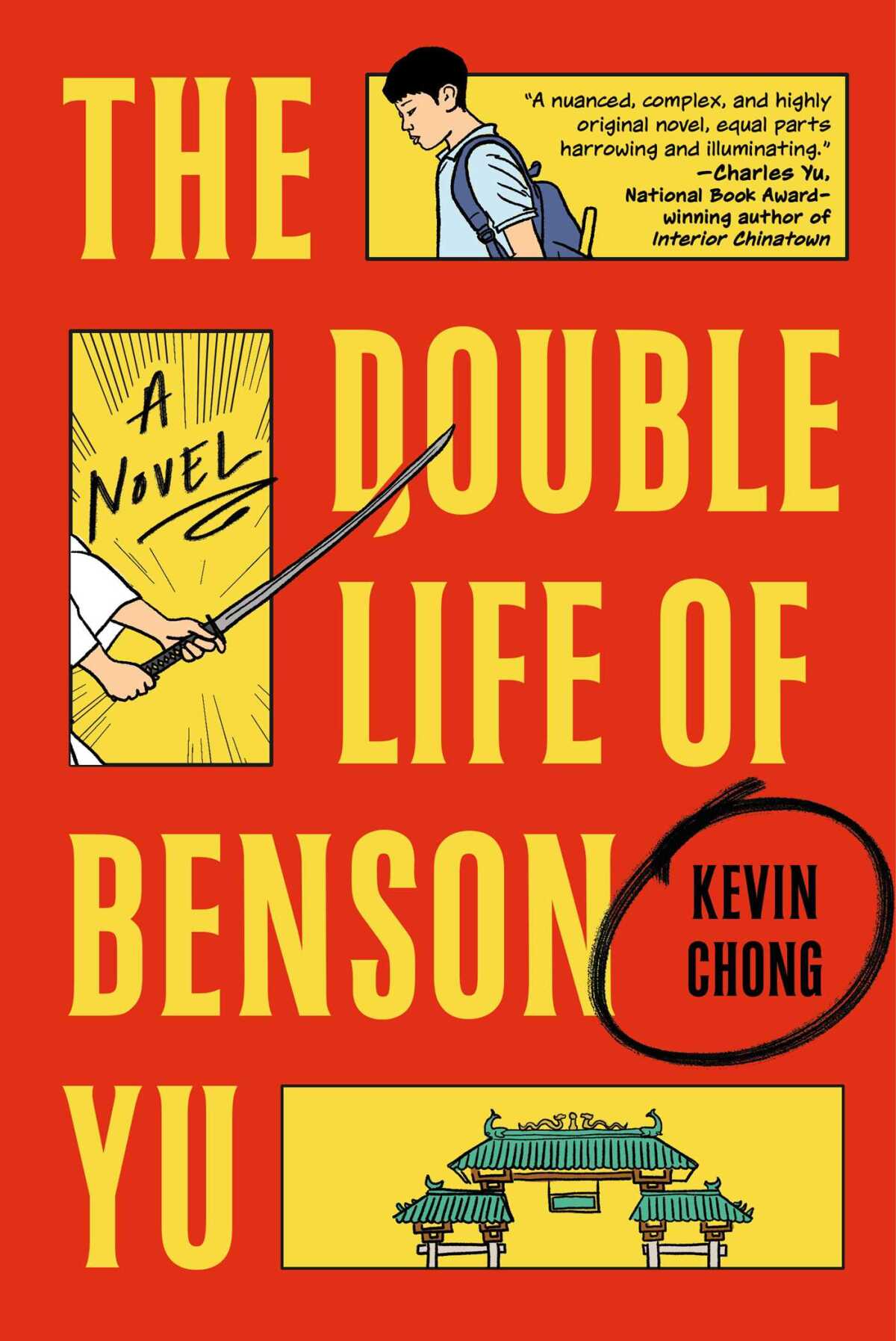

Trauma plot, meet samurai lizard: Kevin Chong on his mind-bending, Chinatown-set novel

On the Shelf

The Double Life of Benson Yu

By Kevin Chong

Atria: 224 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The eponymous main character in Kevin Chong’s “The Double Life of Benson Yu” is a successful comic book creator who is asked to write a memoir. Benson’s childhood was spent in an unspecified Chinatown in the 1980s, living with his grandmother after his mother died. All he knows of his father is that he’s some kind of “bad man.” Their inevitable face-to-face creates a scene that defies genre categories. What begins as realist fiction pivots with a gigantic metaphysical twist, asking big questions about what obligations a writer has to their characters. By blurring the lines between fact and fiction, creator and creation, Chong probes some of the tenderest spots in the process of writing fiction.

Benson produces a series called “Iggy Samurai,” in which animal characters act out a hero’s journey. Iggy is guided by Coyote Sensei, who teaches and protects him. The novel opens with a letter written to Benson by “C,” the real-life mentor who inspired Coyote Sensei. While the fictional sensei is benevolent, Constantine — C — was (and is) clearly not. His letter reveals that he has been “following” Benson’s career. “Maybe you’re not mad at me,” C writes. “Maybe you’ve forgotten about me. If that’s the case, and that seems highly unlikely, here’s a reminder of my existence.”

Your ultimate L.A. Bookhelf is here — a guide to the 110 essential L.A. books, plus essays, supporting quotes and a ranked list of the best of the best.

C’s reemergence forces Benson to rethink his art, which has given him a way to erase the terrible parts of his childhood and transmute them into an idealized adventure. Has he betrayed his history by concealing C’s abuse? In Chong’s riveting novel, the writer’s attempt to control the past falls apart, and he must make himself accountable to the child he once was.

Chong, the author of three previous novels and three works of nonfiction, spoke with The Times via video chat last month about fictional forms of truth, Vancouver’s historic Chinatown and how marriage and parenthood have changed him as a writer.

What inspired you to write about Chinatown in the ’80s?

Let me take you back to my thinking. I started writing the book in March 2020, right in the middle of the lockdown, and one of my inspirations was the Oregon author Willy Vlautin and the book “Lean On Pete.” It’s a great book and movie about a boy who lives at the track.

I’ve written books about horse racing, but [Vlautin’s book] intrigued me because I liked the idea of writing about a boy on his own. Benny [the boy who becomes Samurai] is 12, because it’s a vulnerable age — not-quite child and not-quite teenager. The summer I was 12 I was in Chinatown at my grandma’s in a one-room studio apartment in a housing project. And so spatially, that’s the setting I drew from.

It’s never mentioned which Chinatown it is. Was that deliberate?

I was being vague. My last book was set in Vancouver, and I wanted to not talk about the location. I wanted to just talk about it as a Chinatown and have the audience fill in the blanks. But I think if you were to map out the book, you’d probably use a map of Vancouver‘s Chinatown.

Nonetheless, I left it unspecified. What is different from the 1980s is gentrification and how Chinatowns are hollowed out these days, because a lot of members of Chinese communities live in the suburbs. In a lot of those urban cores, especially in Vancouver, that area is being reclaimed, used for condo developments and things that aren’t related to Chinese people. A lot of these sorts of places are a little bit under siege.

‘Fiona and Jane,’ Jean Chen Ho’s collection of stories, pays homage to friendships complicated by displacement, sexuality and the passage of time.

Benson’s writer’s block kicks in when he’s asked to write a memoir, instead of the comic books that helped him process his past. How do you think switching to prose unmoors him?

I was thinking of somebody who was writing comic books as a kind of an escape, and now he wants to write prose as a way of really trying to confront these issues. He thinks prose narrative is more “adult,” and he wants to be more sophisticated. He’s going to toss away what he thinks of as being more juvenile. “Iggy Samurai” — I thought of it being like “Teenage Mutant Ninja Samurais” or “Samurai Rabbit.” I had to do a deep dive back into that era of comics.

If you’re confronted by somebody who has taken something from you, done something terrible, maybe you’re not in a position to write about it in a way that’s level-headed, that allows for ambiguity. That’s something Benson is trying to figure out, or is learning over the course of the story.

The problem is it’s something huge in your life that inspires the writing. Benson’s approach creates a sort of false binary. Either he doesn’t write about it or he idealizes it.

So Benson’s problem in telling the story becomes your problem in writing the novel: How to confront the past. You found a mind-bending solution.

In retrospect, the way the book developed came to me as a surprise, but it shouldn’t have been. I like a lot of books in which reality folds into itself as a commentary on storytelling. For example, I really liked [Susan Choi‘s] “Trust Exercise,” [Charles Yu’s] “Interior Chinatown” and [Iain Reid’s] “I’m Thinking of Ending Things” a lot. Those are all books that are self-referential and about writing.

Steph Cha shares a meal and some notes on performing identity with the “Interior Chinatown” author.

I was thinking about people I know who have spoken very highly of people who were tormenting them. And when you point out that it sounds like abuse, they get very angry and so much of their sense of self-worth is tied into the relationship with this person. Benson tries to explain away C’s behavior.

And as a writer, I thought about whether there are ethics to trying to humanize a monster. If you turn them into a character and you try to understand them, are you in some ways justifying their actions? Many of them have trauma. That’s what Benson is grappling with as he writes this story.

Benson is also a father, and you’ve written some marvelous essays about being a stepfather and a new dad. Has fatherhood changed your writing?

I would think so, as much as being married. I feel like it’s changed me more than anything else, insofar as marriage makes you come to terms with your limitations as a person. Because you have to justify yourself with someone else.

I was a new father at almost 40. I came in late to that. It definitely gave me a perspective. I have to live a life where I don’t embarrass my children. You don’t want to leave them ashamed of who you are and the legacy you have given them. You have to lead by example.

I feel like every time I write a book, I start the book because something has changed in my life. I don’t write a new book a year, sadly, because I’d like to. I move slowly because I feel I have to have a new outlook for a new book to be justified. It makes sense to be a parent and think about being a parent writing the book.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.