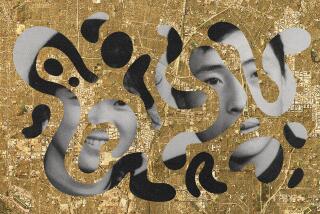

Op-Ed: Why the Monterey Park shooting feels like an attack on Asian America

For thousands of fellow Asian Americans, Monterey Park is our home — even if we don’t live there.

For immigrants and their children, the location of Saturday’s tragedy that killed 11 people was personal and familiar: a dance hall during festive Lunar New Year celebrations. And more so, it was Monterey Park — a town whose Asian strip malls, stores and houses of worship reflect the everyday lives of our ancestors who chose to put down roots in the United States.

Similar to how Grant Avenue and Mott Street served as lifelines for the Chinese in San Francisco and New York, respectively, during the early 20th century, so have Garvey Avenue and Atlantic Boulevard in Monterey Park been lifelines for this community for decades. These are not just neighborhoods; to many, these are sacred sites of cultural preservation and celebration. Monterey Park represents Asian America, today — how far we’ve come and how we’ve built community despite encountering barrier after barrier. This is part of why Saturday hit so hard.

How did Monterey Park become an Asian American hub? From the mid-1800s until the 1960s, foreign- and U.S.-born Asians were often forced to live in less desirable neighborhoods. Low wages and bigotry relegated Asians to places including those areas that became Chinatown. At the same time, these ethnic enclaves protected these residents from critics and racial agitators who questioned their presence in America.

Why are we so quick to ascribe motives in mass shootings, such as the Lunar New Year attack in Monterey Park? Perhaps because, in a country riven with gun violence, so many feel under attack.

When immigration restrictions relaxed following the 1965 Hart-Celler Act, newer waves of Asian settlers acquired incomes that afforded entry into more fashionable parts of the city or in the suburbs. Money, along with increased tolerance of Asian Americans, allowed settlement away from historic Chinatown, Filipinotown and Japantown. Though those enclaves still exist, for the last 30 years these communities have no longer been confined to the city.

Monterey Park reflects this expansion. During the 1950s and 1960s, a small stream of Japanese Americans settled in the community, a rarity during an era of restrictive housing covenants. People of Chinese descent soon followed thanks to Frederic Hsieh. Hsieh — a Chinese investor — purchased property in Monterey Park in the 1970s. He declared it the future “Chinese Beverly Hills,” garnering attention from would-be immigrants from Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Then in the 1980s, some in the area chastised Asian immigrants for not assimilating. Asians quickly found out that their presence was not welcomed by many, as they faced battles over allowing Chinese business signage and efforts to make English the official language of places such as Monterey Park.

How new arrivals remade the east San Gabriel Valley — and assimilated in it.

After a period of growing pains, the temperature cooled down. Many residents unhappy with the demographic changes left the suburb. By the early 1990s, Monterey Park became majority-Asian, with Chinese culture on full display and an array of Asian businesses to patronize. The suburb joined its urban counterparts as an established Chinatown, embodying how millions of Asian Americans live today — inside or close to an ethno-burb where access to Asian goods, services and culture is within a stone’s throw.

Saturday’s mass shooting in Monterey Park rattled Asian America. It triggered feelings the community has been grappling with for the last three years or, arguably, the last two centuries. Was the shooting an act of anti-Asian bigotry? Why did it happen here? These are natural reactions given the long list of violent crimes committed toward Asian Americans, oftentimes in unexpected places: the 2021 Atlanta spa shootings; the killing of Vicha Ratanapakdee in San Francisco the same year; the bus stabbing of an 18-year-old Asian woman in Bloomington, Ind., this month, just to name a few.

To be sure, violence — whether or not it is driven by prejudice — happens everywhere in the U.S. But given the political climate since 2020, it is hard for Asian Americans to not automatically think that hate is the force behind any attack in our communities.

While the motives of the Star Ballroom Dance Studio perpetrator are still being investigated, what is clear is that Asian Americans remain a population forced to live on high alert — even in places we’ve understood to be safe and comfortable. Now this includes Monterey Park.

James Zarsadiaz is associate professor of history at the University of San Francisco. He is the author of “Resisting Change in Suburbia,” a book about Asian American suburbanization and the east San Gabriel Valley.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.