Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Review

Last Words From Two Broadway Legends

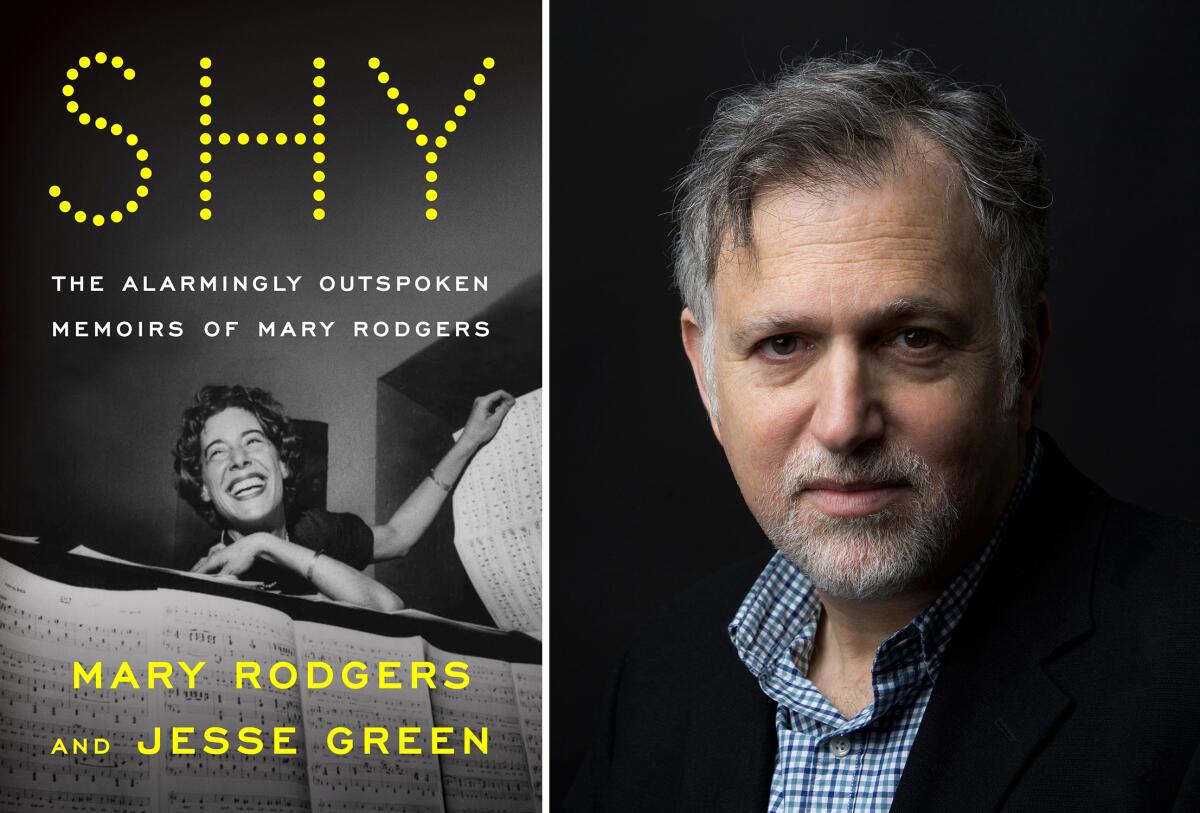

Shy: The Alarmingly Outspoken Memoirs of Mary Rodgers

By Mary Rodgers and Jesse Green

FSG: 480 pages, $35

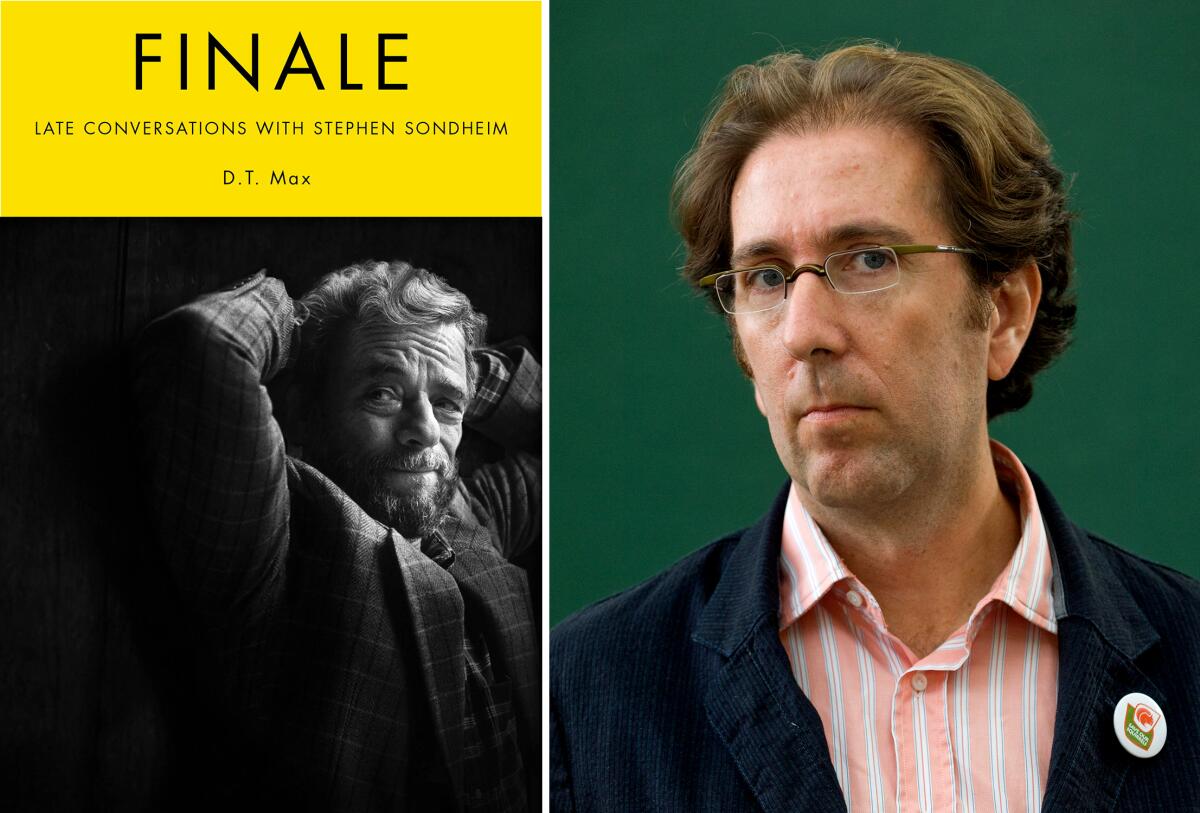

Finale: Late Conversations With Stephen Sondheim

By D.T. Max

Harper: 240 pages, $21

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Would-be writers are often exhorted by well-intentioned instructors to find their “voice,” meaning a sound and style all their own. Unfortunately, this artistic calling card isn’t something that can be willed into existence. In the immortal lyrics of Stephen Sondheim, “You either have it/ Or you’ve had it!”

Two new brazenly entertaining works of theatrical biography are a reminder that “voice” is as essential to the stage as it is to a work of literature.

Mary Rodgers, daughter of musical theater founding father Richard Rodgers and a composer (“Once Upon a Mattress”) and children’s-book author (“Freaky Friday”) of modest renown, knows how to wield a wisecrack. It’s a knack she puts to brassy use in her memoir, “Shy: The Alarmingly Outspoken Memoirs of Mary Rodgers,” co-written with New York Times chief theater critic Jesse Green and published eight years after her death.

Sensibility is something Sondheim possessed in such extreme concentrations that only a shot glass-worth is needed to spike “Finale: Late Conversations With Stephen Sondheim.” The book, by New Yorker writer D.T. Max, consists of a series of interviews conducted in the winter of Sondheim’s life, when the genius behind “Sweeney Todd,” “Sunday in the Park With George” and “Into the Woods” was attempting to write one more landmark show before being feted into the grave.

The crackle of these books has everything to do with the zingy forthrightness of their title characters. Both were weaned on Broadway’s golden age, products of an affluent, largely Jewish milieu where New York’s theatrical movers and shakers cross-pollinated, artistically and otherwise. It’s no surprise that they came to know each other intimately.

Rodgers grew up surrounded by celebrities knocking back scotch in her family’s swanky homes in Manhattan, Beverly Hills and Connecticut. A chubby, sullen, troublemaking adolescent, she moaned about being stuck on an endless merry-go-round of galas (“Blecch, there’s another event for ‘Oklahoma!’ I have to go to”) and rebelled against the narcissism of her coldly controlling parents.

A critic’s tribute to Broadway composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim, a master of storytelling in song.

Son of a prominent New York dress manufacturer father and a designer mother, Sondheim took refuge after his parents’ acrimonious divorce at the Bucks County, Pa., home of Oscar Hammerstein II. Hammerstein, who revolutionized the American musical with his writing partner Richard Rodgers, became both mentor and father figure to the young man who would eventually challenge the old guard with the less ingratiating brilliance of his Broadway musical scores.

It was at Hammerstein’s that a 13-year-old Mary Rodgers first clapped eyes on a 14-year-old Sondheim. “I was dazzled by Steve, completely stunned,” she writes. “I knew right away he was brilliant; he just reeked of talent. Which, not illogically, was always the biggest turn-on for me.”

Sondheim plays an outsize role in Rodgers’ memoir, which chronicles her prolific romantic entanglements with gay men. The pair even gave it a go under the questionable advice of his psychoanalyst. The love trial ended in mutual frustration, but their bond was indissoluble. Who, after all, could better understand the other?

By the time Max shows up at Sondheim’s Manhattan townhouse in Turtle Bay for a New Yorker profile, Sondheim, a reluctant interviewee, is fighting a “slough of creative despond.” He’s trying to make headway on a new musical with playwright David Ives based on two classic films by Luis Buñuel, but age, infirmity and self-doubt are slowing him down.

Sondheim’s inability to finish the work gives Max’s book a faint air of “Waiting for Godot.” Yet failure proves illuminating, as Sondheim dissects the routine of his stymied creative process, until he pulls the plug on Max, explaining that he’d rather not be profiled after all. The death of Sondheim last year increased the value of these sharp-witted conversations and enabled Max to publish them.

Playwrights, directors and other luminaries discuss what it was like to create theater with the Broadway legend, who died Friday.

The successes of both these books illustrate something Rodgers and Sondheim were always the first to acknowledge — that collaboration, no matter how rocky, is the sine qua non of good work.

It would be hard to imagine a better sounding board than Green. He devises a daring, sometimes distracting but ultimately inspired format by saving his commentary for footnotes that contextualize, teasingly contradict and occasionally exculpate Rodgers from her unsparing self-assessments.

Would Rodgers’ life have earned such a voluminous memoir had she not been the resentful daughter of a pillar of the American musical? Probably not. But “Shy” is much more than a work of filial revenge. It’s the story of a bygone theatrical age when New York was the center of the cultural universe and Broadway could still pretend it was at the crossroads.

Rodgers’ scathing honesty jumps off the page in a way that had me imagining a theatrical adaptation along the lines of “Elaine Stritch at Liberty.” “Shy” would also benefit from the structural discipline demanded by the stage. Too many chapters are devoted to musicals that either went nowhere or are largely forgotten today. “Once Upon a Mattress” brought Rodgers out of the shadow of her father, but unless you’re running a high school drama department, who wants to read a lengthy report of its gestation? By the time the chapter “Some Bombs” arrives, it seems as if we’ve been picking our way through a theatrical war zone for years.

Rodgers is aware that her story could come off as poor-little-rich-girl griping. But in her cocktail party recap of Broadway’s heyday, she bears witness to what it was like to be a female composer in a field dominated by men — chiefly her father. In the process, she turns a second-drawer career into a top-drawer performance.

Mary Rodgers, composer of the musical “Once Upon a Mattress” that helped make Carol Burnett a star and author of the “Freaky Friday” story, has died.

Sondheim is, of course, top-drawer throughout. Broadway’s god of mixed emotions, he is captured in Max’s set of interviews and spare commentaries in all his irascible tenderness — his chumminess on display along with his crabbiness.

At a PEN America gala honoring Sondheim for his literary service, Max, seated alongside Sondheim and Meryl Streep, asks his subject to elaborate on the surprising admission that, beyond the New York Times, he’s not a great reader. Streep chimes in that she’s obsessed with reading, to which Sondheim, a born kidder, suggests: “Vogue and Cosmopolitan and the Style section of the Times.”

He’s only being playful, just as he was when he joked, “Now you have a portrait of Meryl’s marriage: It’s called the Bickersteins.” But Max doesn’t sand Sondheim’s rough edges. Nor does he completely edit out his own. He sets himself up as a nonexpert enthusiast of Sondheim’s catalog, hoping an unthreatening posture might lower Sondheim’s defenses. But Max’s writerly ego isn’t easily tamped down.

After reading Sondheim’s two-volume set of collected lyrics and commentaries, Max writes disapprovingly of the “competitive” tone of the book: “Often the point of the story was that Sondheim was right, though not inevitably. He enjoyed recounting a spectacular error, too, But someone was right. I found the approach unsubtle, paradoxically the opposite of his lyrics.”

The candor of these remarks is refreshing. But this is the main takeaway from one of the most remarkable works of artistic self-analysis? The critique isn’t directly shared with Sondheim — Max, also the author of the first biography of the late novelist David Foster Wallace, never loses sight of his submissive role — but the game of matching wits is on.

The first biography of the late author, ‘Every Love Story is a Ghost Story,’ charts his torments and triumphs.

The subject of rhymes turns Max into a club tennis player desperate to hit a service winner against Roger Federer. As a teacher, Sondheim is patient. But when Max takes pride in rhyming vodka with babka in a Purim play spoof song, the master shoots him down.

“It’s a near-rhyme. That’s my point. If you want to do near-rhymes, don’t boast about it. Don’t say, ‘I’m good at rhymes’ and then do near-rhymes.”

The game goes too far when Max points out in an email a slant rhyme from “Bounce,” a problematic show known by various titles. Sondheim’s blistering reply practically has steam coming out of its ears: “The rhyme is sung by a dying man with slurred speech in a state of dementia. That’s the joke. Lower your eyebrow and pay attention.”

These contretemps are not for naught. Beyond revealing the pride of both men, they throw light on the intricate mind behind what Max calls “the Sondheim experience” — “a moment of complex pleasure when the music wakes and tickles and outwits your sluggish brain while the rhymes click like castanets.”

Max’s method results in a curiously touching miniature. “Finale” wouldn’t work as a play, though Harold Pinter might have had a field day with the subtext. But, like “Shy,” it summons to the page a Broadway voice like no other.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.