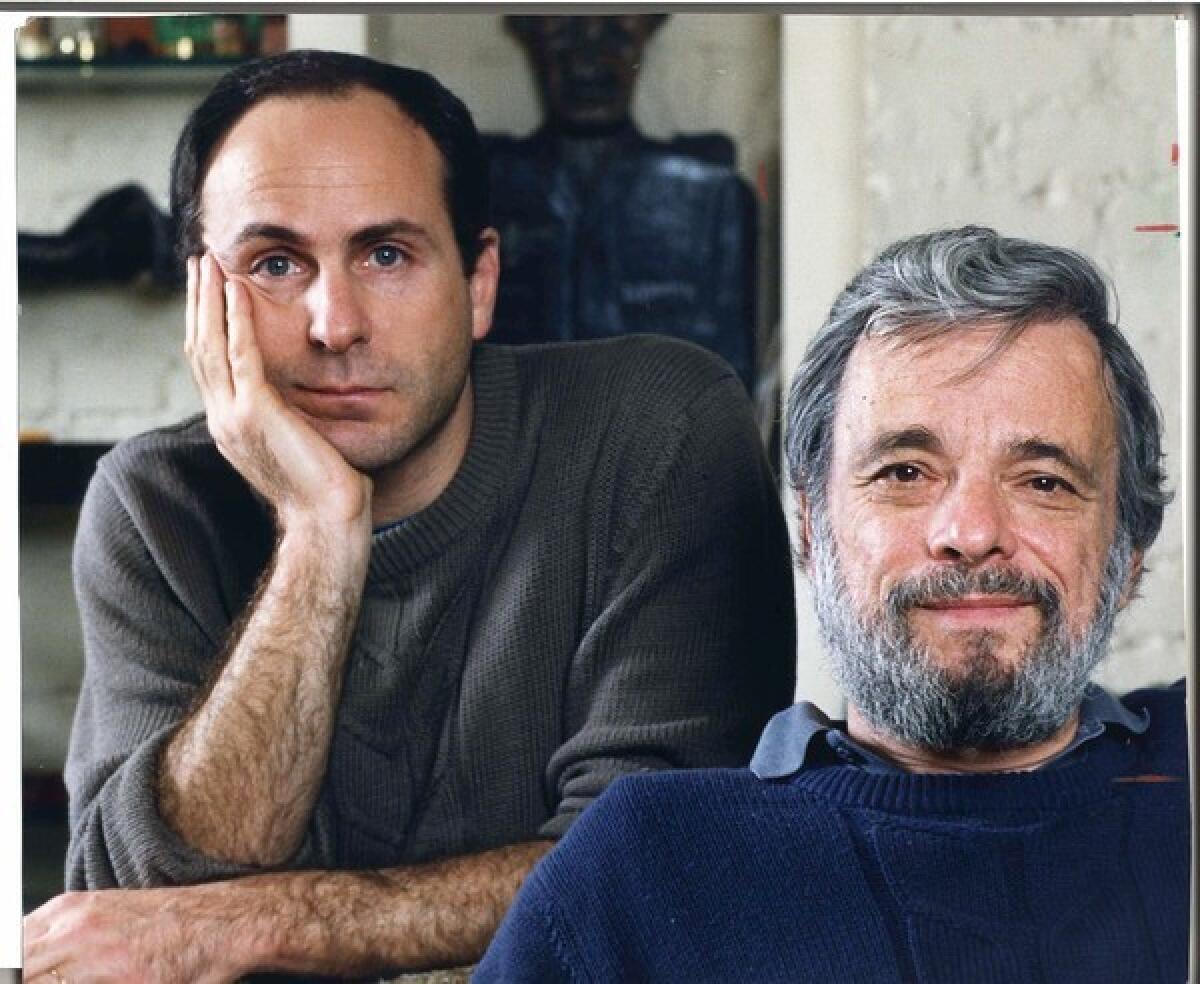

Musical theater icon Stephen Sondheim dead at 91

Stephen Sondheim, the award-winning composer-lyricist who took the Broadway musical to a higher level of emotional complexity than his predecessors in shows such as “Company,” “Follies” and “Sweeney Todd,” has died at his home in Roxbury, Conn.

Sondheim’s death was confirmed by Broadway publicist Rick Miramontez, president of DKC/O&M, but a cause of death has not been disclosed. He was 91.

In a Broadway career launched in 1957 at age 27 as the lyricist for the classic “West Side Story,” Sondheim went on to write the lyrics for the 1959 hit “Gypsy” before writing both the lyrics and music for the 1962 hit “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” winner of the Tony Award for best musical.

But it was as the composer-lyricist of what former New York Times theater critic Frank Rich described in 2000 as “a new, jarring, adult kind of Broadway musical” that Sondheim became “the greatest and perhaps best-known artist in the American musical theater.”

As Tony-winning actor Hugh Jackman reflected on Twitter, “Every so often someone comes along that fundamentally shifts an entire art form. Stephen Sondheim was one of those.”

It began with “Company,” a 1970 concept musical about a commitment-averse New York City bachelor named Bobby that opens with his friends — five couples — waiting for him to show up at his surprise 35th birthday party. The nonlinear show unfolds through a series of vignettes that explore modern marriage and relationships as Bobby visits with the different couples.

The long-running show, with a book by George Furth, launched Sondheim’s longtime collaboration with director Harold Prince and won six Tony Awards, including one for best musical.

“Sondheim changed musical theater,” the late Gary Gardner, the former chair of the Ray Bolger Program in Musical Theater at UCLA, told the Los Angeles Times in 2010. “After the great book musicals of Rodgers and Hammerstein, we had a period of diminishing creativity. Then we ran into rock music [with ‘Hair’], and it’s like, ‘Oh, no.’ Suddenly, with ‘Company,’ we have a new savior.”

Sondheim, 91, whose work is driving this year’s holiday cultural season, was rousingly welcomed at the production’s triumphant reopening.

As a budding teenage composer-lyricist in the 1940s, Sondheim had been mentored by close family friend Oscar Hammerstein II, the renowned lyricist and librettist for “Oklahoma!,” “South Pacific” and other crowd-pleasing musicals.

But as San Francisco Chronicle theater critic Steven Winn wrote in 2000, Sondheim transformed the craft “with his own linguistic powers and thematic range, taking on subjects — from emotional ambivalence to cultural relativism and presidential assassinations — undreamed of by his mentor.”

Observed Gardner: “With Hammerstein, you felt wonderful when you left the theater. But with Sondheim, you realized the angst of living in the late 20th century.”

Sondheim and Prince went on to collaborate on “Follies,” “A Little Night Music,” “Pacific Overtures,” “Sweeney Todd” and “Merrily We Roll Along,” which closed after only 16 performances but came to be regarded as an overlooked triumph.

In the early ’70s, Sondheim won Tonys for his music and lyrics three years running for “Company,” “Follies” and “A Little Night Music.” He also won Tonys for his music and lyrics for “Sweeney Todd” in 1979, “Into the Woods” in 1988 and “Passion” in 1994. (His personal Tony Awards tally stands at eight, including a lifetime achievement honor in 2008.)

In 1985, Sondheim and librettist James Lapine’s musical “Sunday in the Park With George” was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for drama.

Sondheim’s best-known song — the haunting “Send in the Clowns” from “A Little Night Music” — won a Grammy as song of the year in 1975, performed by Judy Collins.

Sondheim was a Kennedy Center Honors recipient in 1993 and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama in 2015. He also won an Academy Award for his song “Sooner or Later (I Always Get My Man),” which was performed by Madonna in Warren Beatty’s 1990 film “Dick Tracy.”

As news of Sondheim’s death spread, writer and podcast host Louis Virtel tweeted, “Stephen Sondheim has been receiving lifetime tributes since around 1973 and still it feels like we’ll always find something else to celebrate about him.”

“To sing a song of Sondheim’s is a singer’s reward,” Barbra Streisand said onstage at a star-studded 75th birthday tribute to Sondheim at the Hollywood Bowl in 2005.

“It’s a gift, often a challenging and complex one but always dazzling — dazzling in its intelligence, its wit, its poetry and its passion,” she said. “His music is constantly fascinating, his lyrics are like scenes that call upon the singer to be an actor, the actor to be a singer.”

Sondheim leaves behind a body of work that has already touched generations, as evidenced by the musical theater luminaries paying respect on social media.

“He gave me so much to sing about,” tweeted frequent collaborator Bernadette Peters. “Thank you for your vast contributions to musical theater.”

Added singer and actress Lea Salonga: “We shall be singing your songs forever.”

Anna Kendrick, who played Cinderella in the 2014 film adaptation of “Into the Woods,” said on Twitter, “I was just talking to someone a few nights ago about how much fun (and f—ing difficult) it is to sing Stephen Sondheim. Performing his work has been among the greatest privileges of my career.”

Audra McDonald, who participated in his 80th and 90th birthday tributes, tweeted simply, “Thank you Steve. Thank you.”

Sondheim enjoyed a 2019 moment when his songs were interwoven into the story lines of “Marriage Story,” “Joker” and “Knives Out,” and filmmaker Richard Linklater announced he would be filming an adaptation of “Merrily We Roll Along.”

There is currently a “Company” revival on Broadway, and Steven Spielberg’s new take on “West Side Story” will open in cinemas Dec. 10. Both projects had been delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In advance of Friday evening’s performance of “Company,” director Marianne Elliott issued a statement, dedicating the show to Sondheim. “We have lost the Shakespeare of musical theatre,” she said. “The joy of working with him was that he knew theatre could and should evolve with time. He was always open to the new.”

An only child, Sondheim was born March 22, 1930, in New York City. His father was a successful dress manufacturer and his mother the chief designer. Sondheim spent his early years living in the landmark San Remo apartment building on Central Park West.

The precocious Sondheim, as his mother later told Newsweek magazine, began “picking out tunes on the piano” when he was 4, and he could read the New York Times at 5.

When Sondheim was 10, his father left his mother for a younger woman and Sondheim’s mother transferred him from a private school to the New York Military Academy in Cornwall-on-Hudson.

Sondheim is said to have despised his mother, who won custody of him in the divorce and forbade him to have contact with his father.

After his father left, Sondheim says in Meryle Secrest’s 1998 biography “Stephen Sondheim: A Life,” his mother “substituted me for him. And she used me the way she had used him, to come on to and to berate, beat up on. What she did for five years was treat me like dirt, but come on to me at the same time.”

In the 1970s, when his mother was about to receive a pacemaker, she wrote him a letter in which she told him, “The only regret I have in life is giving you birth.” Although Sondheim continued to support his mother financially, he wrote back to say he no longer wanted to see her, and he did not attend her funeral when she died in 1992.

Young Sondheim found emotional refuge at the home of Oscar and Dorothy Hammerstein, who had become friends of his mother’s. After meeting the Hammersteins’ 10-year-old son Jamie in 1941, Sondheim spent the summer at their farm in Bucks County, Pa.

Although his mother soon bought a nearby farm, Sondheim remained a fixture at the Hammerstein home.

“Oscar was everything to me,” Sondheim told Newsweek in 1973. “He was a surrogate father and I wanted to be exactly like him. In a way, I still do.”

In 1946, while attending the George School, a college-preparatory school in Newtown, Pa., Sondheim wrote the music and collaborated on the lyrics for a hit campus musical about life at the school called “By George.”

“I thought it was terrific, so I asked [Hammerstein] to read it as if he were a producer and didn’t know me,” Sondheim told Newsweek. “The next day he called me over and said, ‘It’s the worst thing I ever read in my life, and if you want to know why I’ll tell you.’

“That afternoon, I learned what songwriting was all about — how to structure a song like a one-act play, how essential simplicity is, how much every word counts and, above all, the importance of content, of saying what you, not other songwriters, feel.”

Hammerstein also mapped out a years-long personal course of study for Sondheim involving writing the book, music and lyrics for four musicals that culminated in writing an original show.

Sondheim, who served as a gofer during summer rehearsals for the 1947 Rodgers and Hammerstein musical “Allegro,” graduated from Williams College in Williamstown, Mass., with a bachelor’s degree in music in 1950. He received the Hutchinson Prize, the school’s top honor in music, which enabled him to spend two years studying composition and theory with avant-garde composer Milton Babbitt.

In 1953, Sondheim landed his first professional job, via his Hammerstein connection: writing scripts for the TV sitcom “Topper” in Hollywood for five months.

He later was hired to write the lyrics and music for a musical to be called “Saturday Night.” But his hopes of making his Broadway debut with the show were dashed when the project ended with the death of its producer in 1955.

But at a party later that same year, Sondheim ran into playwright Arthur Laurents, who was working with composer Leonard Bernstein on the idea of doing a modern-day musical based on “Romeo and Juliet.”

Sondheim, whose various credits include co-writing the screenplay to the 1973 movie mystery “The Last of Sheila” with actor-friend Anthony Perkins, was described as extremely private, emotionally reserved, irascible, sardonic, complex and obsessively self-critical.

“Steve is a perfectionist,” said Bernstein, who wrote the music for “West Side Story.” “He’s extremely critical, very sour. … Some people are terrified of his opinion. But he’s hardest on himself.”

In an interview with Time magazine in 1987, Sondheim said that despite various infatuations, he had “never” been in love and had always lived alone. He lived alone until he was 61, when he met and fell in love with Peter Jones, a young songwriter, according the New York Times. The two eventually went their own ways but remained friends. In 2017, Sondheim married Jeffrey Romley.

Sondheim said he had not been bothered by his years of living alone.

“God knows I spent enough hours on the psychiatrist’s couch discussing it, but it’s partly what you’re used to as a kid. I grew up entirely, as one friend puts it, as an ‘institutionalized child’ in that I was brought up either by a cook, a nanny or a boarding school or camp.”

As he viewed it, he never really had parents, “so I never had any role models of what it was like to have a family feeling. I was not miserable; at least I didn’t think I was, so I didn’t miss it.”

Something he only realized in his adult life, Sondheim said, “is that one of the reasons I love writing musicals is that musicals are collaborations. I love the family feeling.”

McLellan is a former Times staff writer. Times staff writer Dorany Pineda contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.