Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

On the Shelf

The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man: A Memoir

By Paul Newman, edited by David Rosenthal

Knopf: 320 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Melissa Newman once told her father — Paul Newman, that Paul Newman — that she imagined him standing in front of a giant billboard featuring a photo of his famous, gorgeous face. But in her imagining, she said, the movie star himself stands beneath the photo: “Just a little person with a little sign saying, ‘It’s me. I’m here.’”

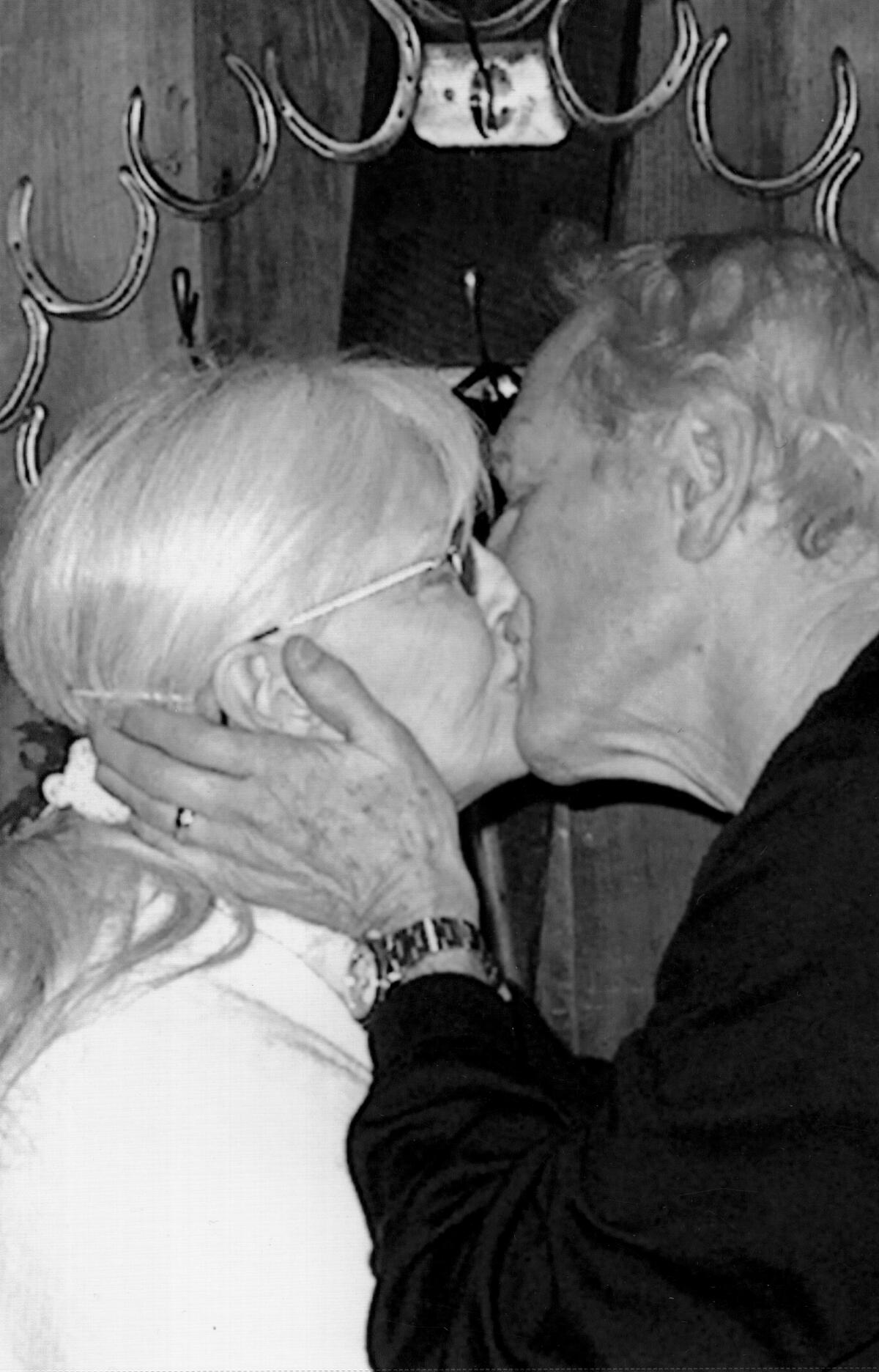

That desire to be seen as his true self is at the heart of his posthumous memoir, “Paul Newman: The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man.” Filled with inner turmoil and self-doubt, much of it fueled by family dysfunction, the unusual release comes on the heels of the HBO docuseries “The Last Movie Stars,” which used a wider lens to explore the lives and loves of Newman and wife Joanne Woodward. Both draw on the same remarkable cache of interviews — material that a conflicted Newman created and then abandoned.

In 1986, Newman asked his closest friend, Stewart Stern, the screenwriter of “Rebel Without a Cause,” to interview him but also to get family, friends and colleagues to speak honestly about him. Newman revealed the torment of an unhappy childhood that still held sway over him, talking as frankly about drinking and marital problems as he did about his work.

“He was trying to figure out how to get to a better place,” said Newman’s youngest daughter, Clea Newman Soderlund, who wrote the book’s afterword. (Melissa wrote the foreword.) “It was a long internal journey, and the interviews were part of his process.”

And yet, in 1991, Newman decided the journey was done; he destroyed the interview tapes.

He lived an additional 17 years, dying shortly after Woodward — long overshadowed but an Oscar and Emmy winner herself — was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Gradually, Melissa Newman says, Hollywood’s golden couple faded from public conversation. The daughters decided to honor their mother with a documentary on her career. That project proved a tough sell until their childhood friend Emily Wachtel made an astonishing discovery. And then another.

The blue-eyed star of ‘The Hustler,’ ‘Cool Hand Luke’ and ‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’ was at home. He had long battled cancer.

“I was looking for archival materials for the documentary, and in their laundry room I found a locked file cabinet,” said Wachtel, who served as producer on the HBO series and shepherded the book into existence. She called a locksmith and discovered a lost treasure: 14,000 pages of Stern’s interviews with everyone — including John Huston, Sidney Lumet, Tom Cruise and Newman’s first wife, Jackie Witte.

Wachtel pitched it as a potential book, but a literary agent was hesitant. Still, the family friend kept digging through archives, hoping it could all be fodder for the documentary, until she made her second find: transcripts of Newman’s own conversations with Stern. “I was in a storage unit, and there were two boxes that had been put there by movers that said, ‘PN History,’” Wachtel recalled. “Nobody knew they still existed.”

Soderlund believes her father saved the pages because he wanted this story told. Melissa Newman added that in the transcripts, her father gave permission for their use, saying, “It would be nice to straighten up the record,” and adding, with typical modesty, “if there is any interest in a biography.”

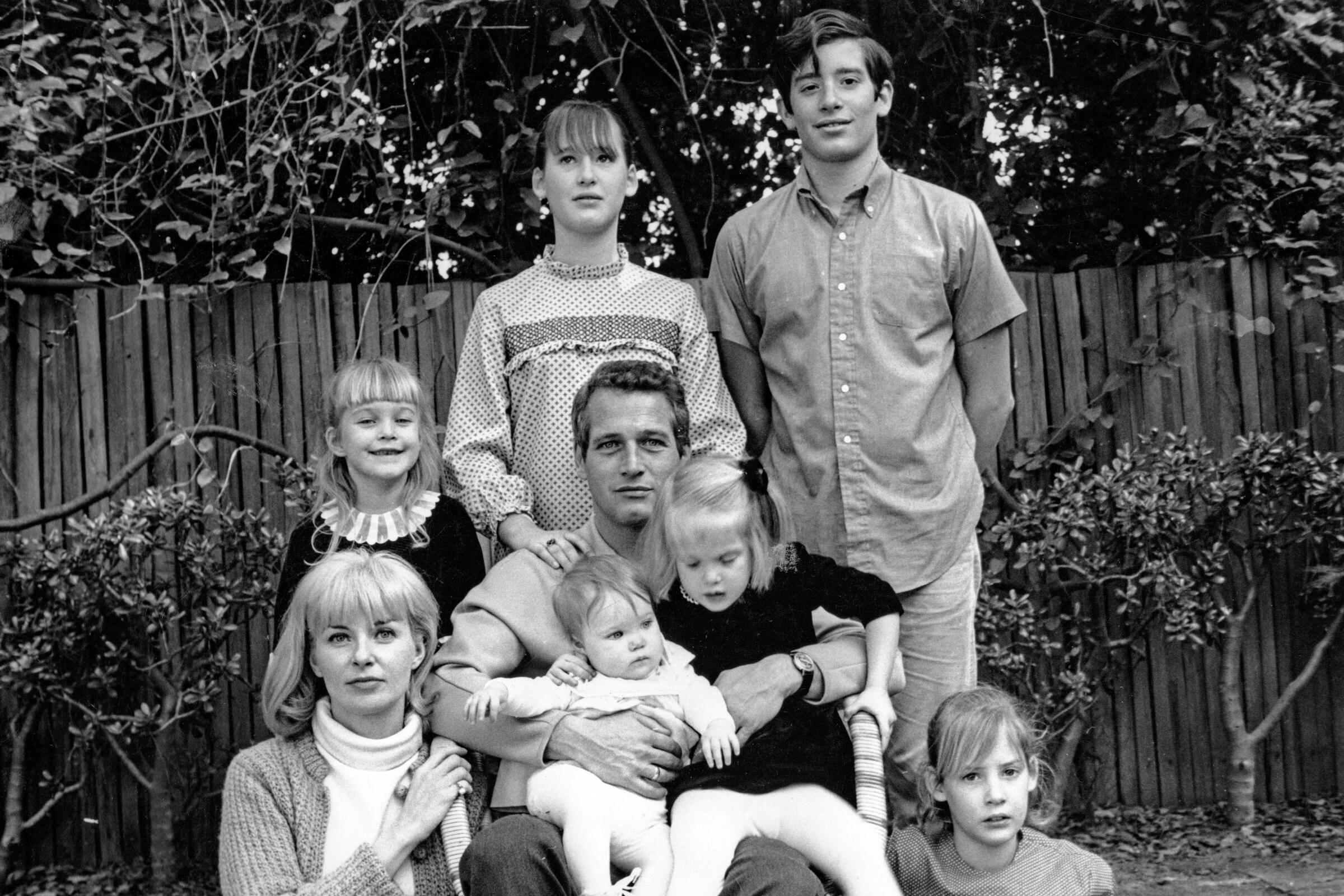

That consent prompted them, after discussing it with their other three sisters, to pursue a book deal. (Newman’s son, Scott, died of a drug overdose in 1978, a loss explored in depth in the book.) Armed with Newman’s own words, Wachtel and the agent hired someone to craft a book proposal, which prompted a bidding war. Knopf won the rights, and last summer, editor Peter Gethers — whose father had, coincidentally, written one of Newman’s first live TV shows — brought on veteran journalist and publisher David Rosenthal to shape the pages into a narrative in six months.

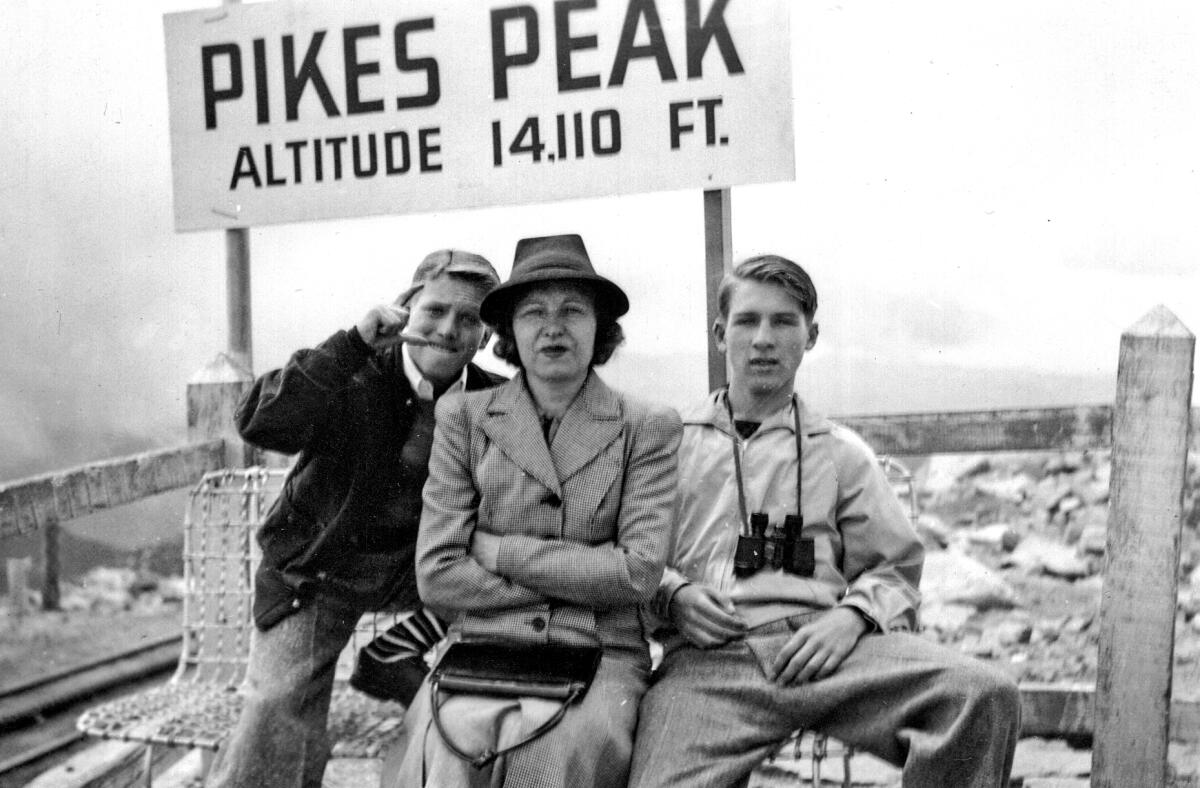

“The ‘Pages of Paul’ existed only on paper and were not really organized,” Rosenthal recalled. After reading through the material, he decided to tell Newman’s story chronologically, because his childhood informed everything about “the damaged person he was. You almost had to look away from the page because it was shockingly intimate.”

While the book might have fared better commercially with anecdotes about hanging with Robert Redford, the childhood trauma was more revealing. “His voice is astonishing,” Gethers said, “and when he said his mother viewed him merely as ‘decoration,’ it was so potent and sad it made my stomach hurt.”

Ethan Hawke, whose docuseries ‘The Last Movie Stars’ explores the pair, says they regularly shifted ‘who’s the rose and who’s the gardener.’

Rosenthal wasn’t given a page count, but he says the voluminous material lent itself to being “relatively succinct”; he mostly avoided duplicating stories Newman had told in major interviews. Instead, the Hollywood stories were often more intimate, focusing, for example, on how Newman tried hard to impress Huston and was pushed to greater depths by Lumet.

“It feels like it cuts to the point all the way through,” Gethers says. “There’s enough other material for more books, but I think this is definitive.“

The family approves of the finished product; yet family members freely discuss debates they had along the way — and various quibbles that remain. While Melissa Newman thought the book would be “a lot longer,” the daughters are pleased with the final result. “We definitely made our thoughts known,” says Soderlund. “It was a good team effort, and you don’t always get everything you want.”

One point the sisters pushed back on was the book’s tone. The editors “became entranced with the insecurity and doubt, because it was so different from what people know or imagine,” says Newman. “They really mined the dark stuff, but there was a lot of other material where he talked about process and making art.”

She added that Stern had pushed and prodded her father in the interviews, which could make him “a little grouchy,” and that when the questions are removed, “the tone seems a little dark.” She also would have preferred less material about how her father handled Scott Newman’s struggles, but she acknowledges it might help others. “There’s no perfect way to navigate that even with all the resources in the world,” she said. “It’s messy, and everybody tries as hard as they can, and you still blame yourself.”

Soderlund said the published reflections failed to convey how generous he was. “It also misses his joy in doing funny things — he was a goofy guy with a terrible sense of humor.” To better balance the book, the daughters successfully fought for the inclusion of more outside voices “to show the light he was emanating for a lot of other people,” Newman said.

Refusing to romanticize his nonconformist characters, the star put his sex appeal to complicated and fascinating use.

Ultimately, Gethers said, the book shifted from 80% to 70% Newman in response to the feedback. “It’s important for people to realize that someone who is the epitome of cool and sexiness and confidence on the surface is also filled with self-doubt but fights through it and succeeds anyway,” Gethers said. “They wanted an honest book, but not one so slanted by his self-doubt that it wasn’t accurate. I can’t say I resisted.”

Soderlund has one other regret: She wishes all of Newman’s daughters had been interviewed. It would have showed, she believes, “how he worked really hard after that period of time to have a really meaningful relationship with us.” She seeks to redress this in her afterword, writing that “he evolved immensely in the last quarter of his life; he became more present and reveled in giving back.”

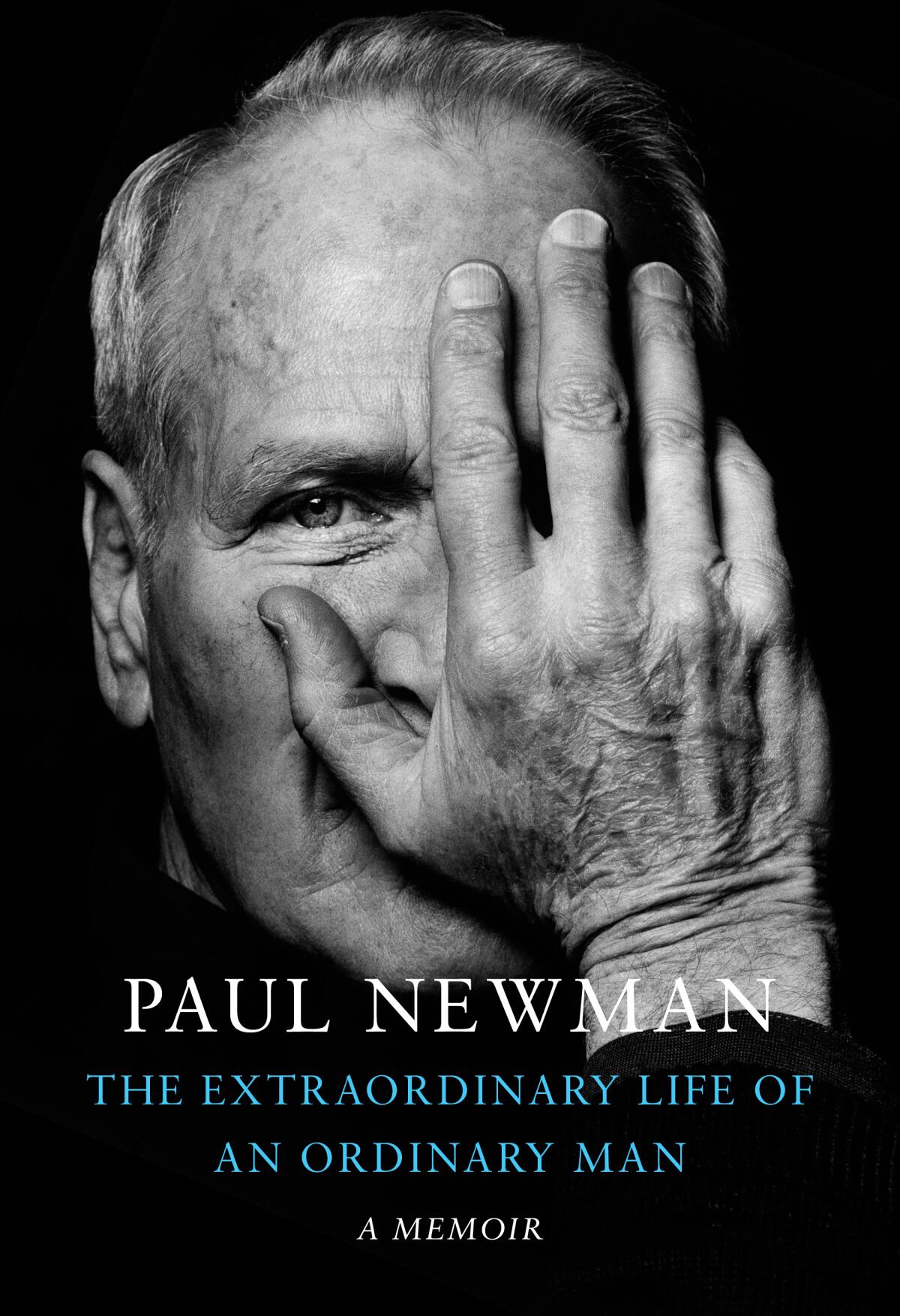

The finishing touch was finding the perfect cover. The art director brought in 20 images of Newman in “The Hustler,” “Hud” and other films, Gethers recalled. “Your reaction is just, ‘This guy is so good looking.’ They were gorgeous, but there was a lack of intimacy to them.”

The sales and marketing team wanted a sexy cover, of course. But when Gethers saw an image of an older Newman with his hand covering half his face, he knew immediately that that was the money shot. This is a man wary of revealing himself to his audience but doing it anyway — or perhaps a man who, having fully revealed himself, is now trying to pull back. Or even a man looking inward, as he did in the memoir, half eager and half afraid to see what he will find.

On this choice, Melissa Newman fully agrees: “It perfectly illustrates the contents.”

The photograph is also in black and white — which made it, Gethers said, a fitting final tribute to Newman’s quest to be seen for who he really was. Newman often felt Hollywood exploited his beautiful blue eyes; Soderlund says he would have appreciated a cover without them. “He was so much more than his eyes and beautiful face…. I think this picture shows that beautifully.”

Three new books — “Dream State,” “Hollywood Eden” and “Rock Me on the Water,” examine savvy pop-culture myth-making by and about the Golden State.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.