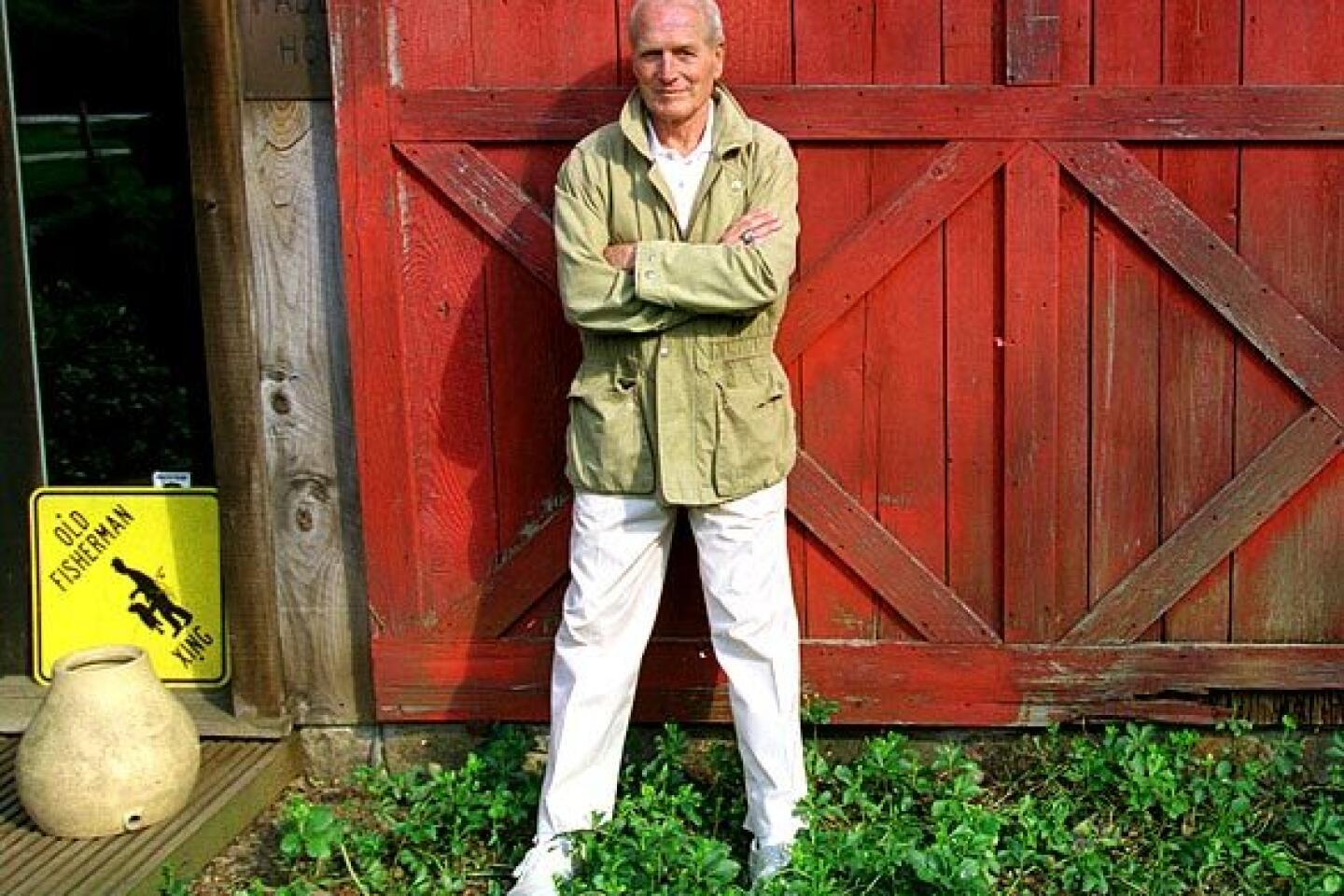

Paul Newman wielded his beauty like a craftsman

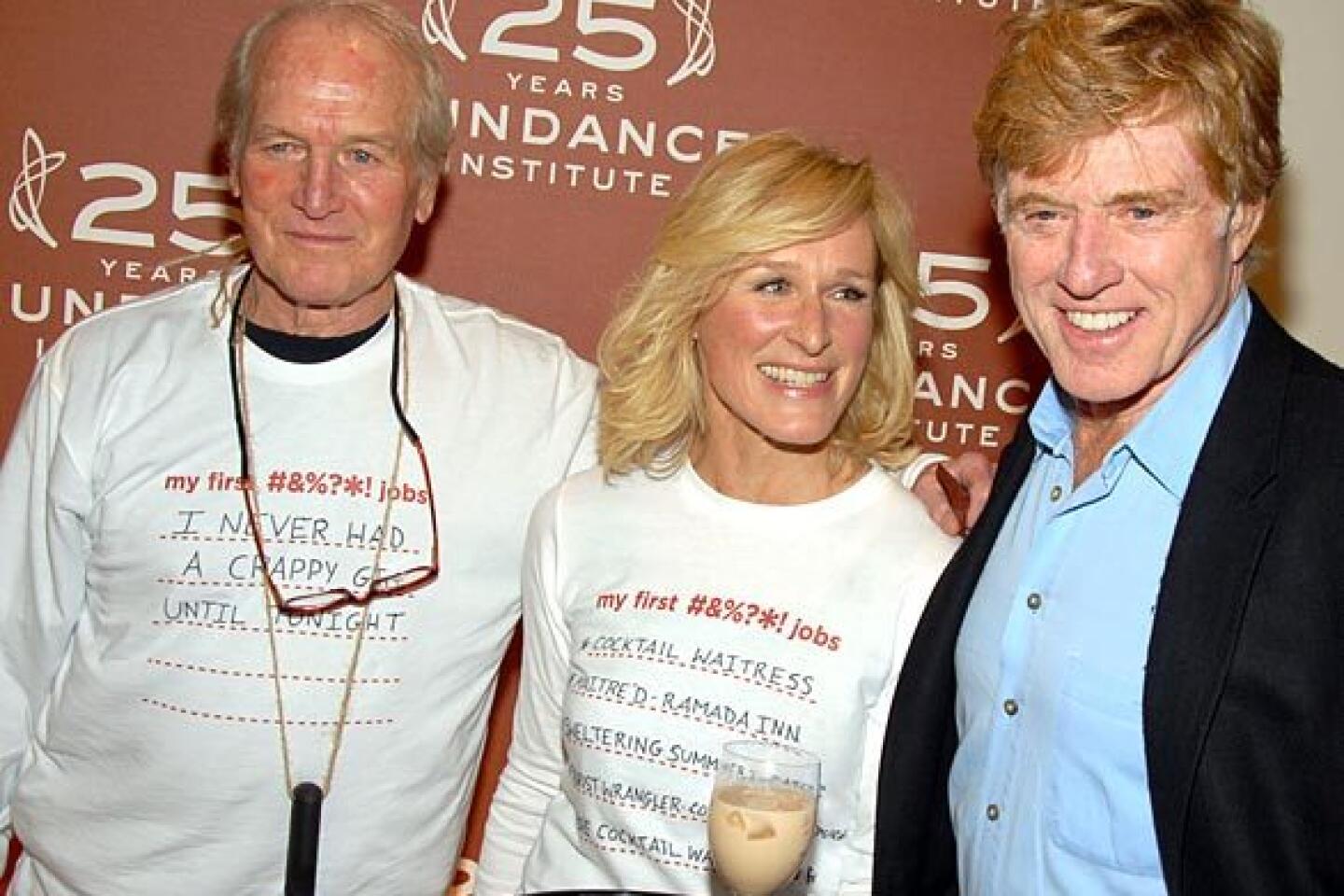

Paul Newman, that pure and concentrated essence of classic movie stardom, reinvented himself a couple of times in the span of his long career, until he ended up playing the kind of guy he might have become had he never left his native Shaker Heights, Ohio: an ultra-conservative, cold-fish Midwestern lawyer, married for decades to the same woman (see his performance in the Merchant-Ivory jewel box “Mr. And Mrs. Bridge,” from 1990).

But he’ll be best remembered for playing the polar opposite, a recurring persona he took up and reprised from 1958 through 1969, the nonconformist ne’er-do-well, idolized by criminals and women who knew better, reviled by authority and tradition.

A quick survey of the characters Newman inhabited during that time reveals several recurring traits. There’s the matter of his alarming beauty, which was almost always treated as a complicating factor in his characters’ lives. An otherworldly Adonis, he could have simply gone the tuxedo route, but he had a fondness for playing rough-and-tumble losers, drunks, failures and outcasts. His rebel nonconformists were often nonconformist in pointless, self-serving, usually self-destructive ways that he refused to romanticize.

Remarkably, he was almost never paired with the great beauties of his time, appearing instead opposite actresses of lesser looks than his. Piper Laurie, Patricia Neal, even Joanne Woodward -- whom he would eventually marry and remain with for life -- played characters in thrall to his charm and charisma, usually to their detriment. The most beautiful actress he was ever cast opposite also happened to play the character he rebuffed most cruelly: Elizabeth Taylor’s sex-starved Maggie, longing hopelessly for passion from his closeted gay Brick in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.”

It’s not the sort of thing you see much at the movies anymore -- the examination of the male bombshell, a character as irresistible as he is casually destructive to himself and others. It’s hard to imagine a modern-day movie star putting his sex appeal to such complicated, fascinating use. Even when Newman’s characters liked women, he wasn’t very good to them. In “Hud,” he tried to rape his housekeeper. In “The Hustler,” he took up with a disabled alcoholic who, for a while, supported him. In “Sweet Bird of Youth,” he hustled rich older women for money and an entree into show business, repeatedly abandoning the girl he loved to pursue his dream of stardom. In “Cool Hand Luke,” where the only woman in sight was his mother, he broke her heart.

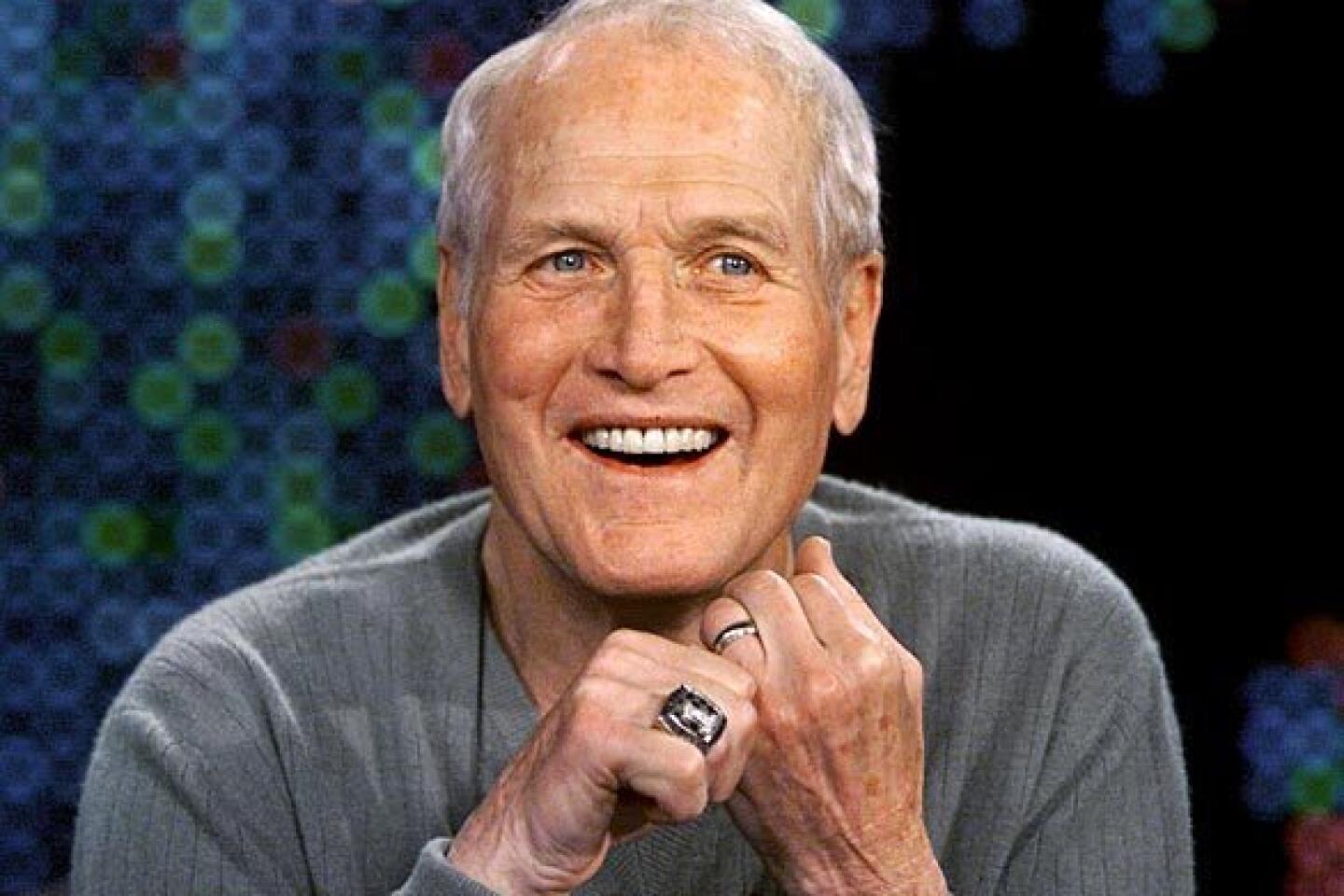

And yet the Paul Newman anti-hero, a rake if ever there was one, was irresistible to men and women alike. (What is “Cool Hand Luke” if not a polyamorous bromance writ large?) His early characters were at once vulpine and preyed upon; twice, in separate films, he uttered a variation of the line, “Everyone wants a piece of me.” Newman was savvy enough to know when to start moving away from the roles that used his beauty as a basis for his characters. And that intelligence and grounded self-awareness shines through in all his performances. The slow Newman grin, the same one that charms George Kennedy in “Cool Hand Luke,” made it clear that he was always aware of the effect he had on others, and when and how to modulate it for maximum impact.

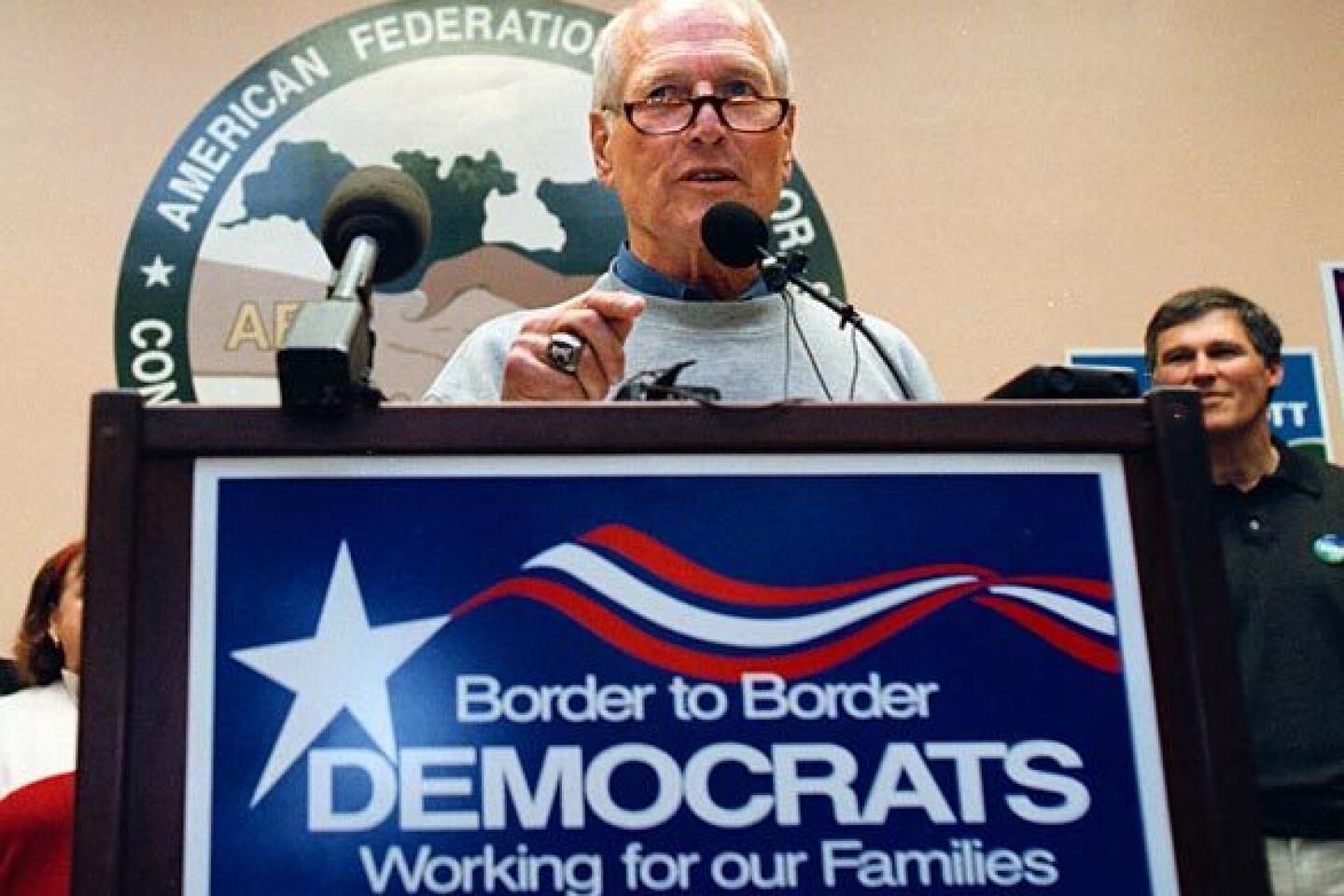

His characters’ vanity got them into worlds of trouble, but Newman’s complete lack of it came across clearly in the roles he chose and the life he lived.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.