Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Los Angeles has its share of august cultural institutions — its starchitect museums, its grand library, its stately universities. But if you want to know where its literature evolved, you have to look into the uncredentialed places. Below, as part of The Times’ Lit City project, are the beginnings of a grass-roots tour of the city’s literary history: a zigzag journey through time and space, from a 130-year-old bookstore to a scrappy 21st century art gallery, a 1930s bookshop speak-easy to a workshop built from the rubble of the ’60s — as well as an upscale market where a Nobel laureate and a world-famous composer might have come to blows. Just a few of the unexpected wellsprings of history.

By Lynell George

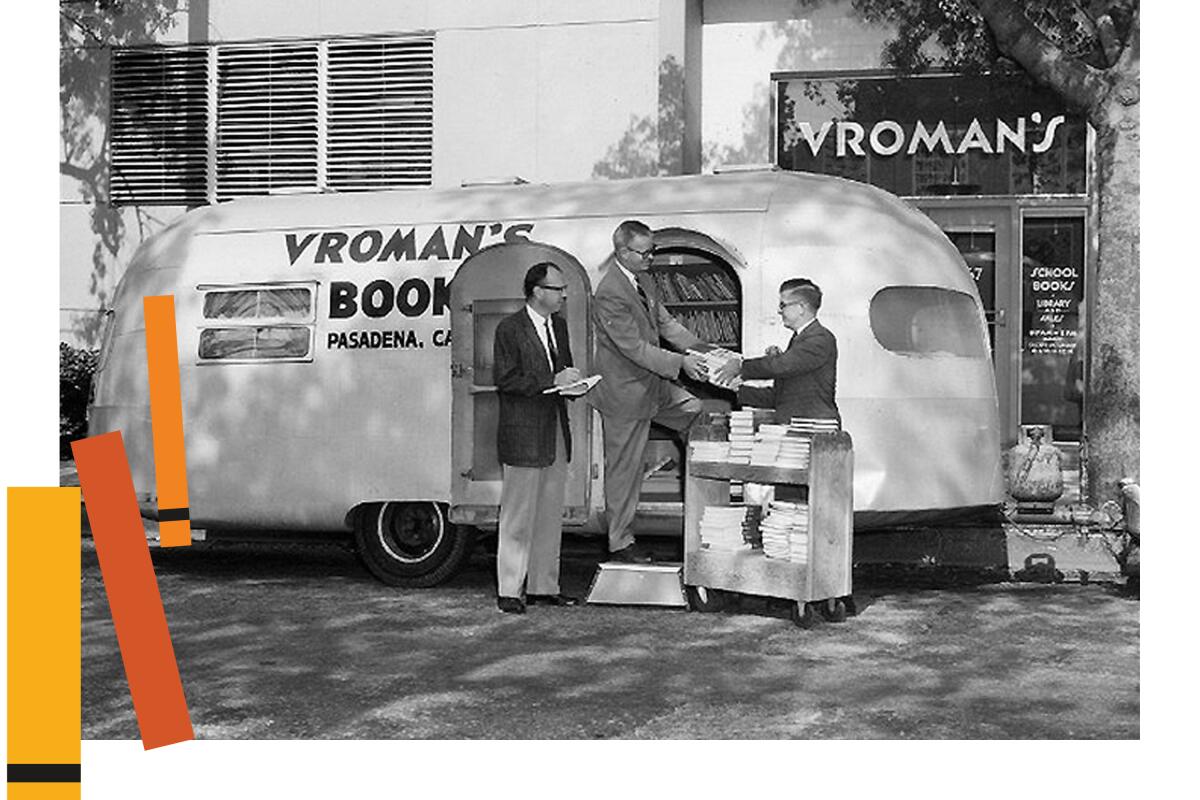

A childhood dream of mine had been to live around the corner from a well-appointed bookshop. In my college years, working as a bookseller in Century City, I understood how important a vivid book community could be. Some years back, when I moved to the San Gabriel Valley, I counted on Vroman’s, a brisk 20-minute walk away, to be my doorway to making a new home.

The store’s founder seemed to have anticipated this yearning. Like many wayfaring hopefuls, Adam Clark Vroman, an ex-railroad worker, bibliophile and photographer, was lured to California by its sense of possibility. In 1892 he arrived, hoping to find a sunshine cure for his new bride’s tuberculosis. The cure didn’t take, and after two years back East, she died. Vroman ventured back to the San Gabriel Valley to craft a new chapter.

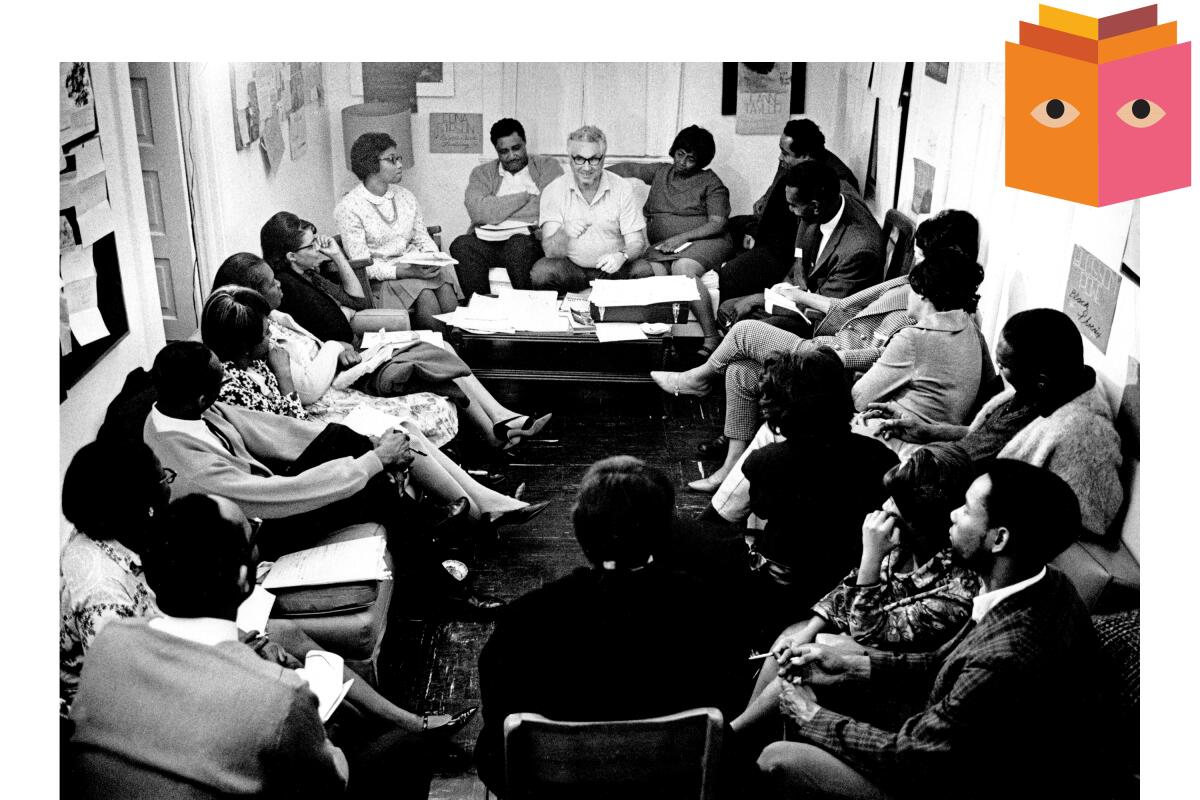

By Michael Datcher

Across from my writing desk there is a framed black and white photo: Four young Leimert Park poets sit front row at the Watts Towers watching a panel of four alumni of the Watts Writers Workshop. I’m the young poet with the black journal in his lap and wonder in his eyes. I’m the one who, many years later, serves as steward to the workshop’s successor, the World Stage Performance Gallery.

For decades, the poets of Watts and Liemert Park have responded to anti-Blackness with Black excellence. Articulating the full humanity of Black folk, they offered an inspiring counternarrative to dehumanizing treatment. “How can your low opinion of us be true when we can write high art?” This question for America drove those poets — the elders and those my generation — to show Black beauty to America and to ourselves.

By David Ulin

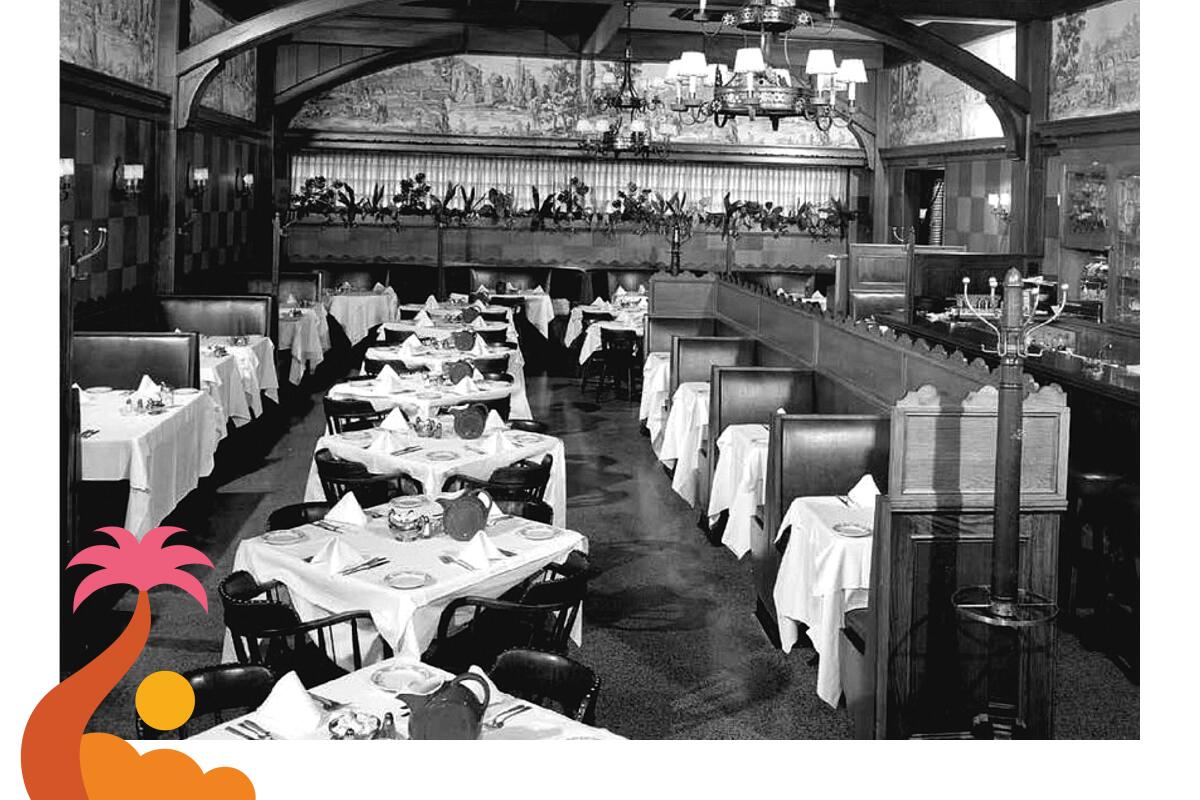

Raymond Chandler used it as the model for Arthur Geiger’s bookstore in his 1939 debut novel, “The Big Sleep.” Edmund Wilson took the title of “The Boys in the Back Room” — his 1941 study of California authors James M. Cain, John O’Hara, John Steinbeck, William Saroyan and F. Scott Fitzgerald — from the clubhouse in the rear. Budd Schulberg called it “the nearest thing to a Left Bank we had out there.” For all of them, as well as other writers in Los Angeles during the 1930s, the Stanley Rose Book Shop, located at 6661½ Hollywood Blvd., next door to Musso & Frank, was both gathering space and watering hole, a home away from home.

Rose was, by all accounts an unlikely littérateur: a rough-hewn Texan who, according to Jay Martin’s “Nathanael West: The Art of His Life,” “had not gone beyond the fourth grade and had not learned to read until he was wounded in World War I.” In 1928, as a partner in the aptly named Satyr, another Hollywood bookshop, he spent 60 days in jail after being convicted of pirating Chic Sale’s salacious novel “The Specialist.” He opened his eponymous store in 1935 with financial assistance from crusading journalist Carey McWilliams and became Saroyan’s agent. He was also a soft touch who, as Martin writes, “loved writers, lent them money, let them sign his name at Musso & Frank’s.” Such profligacy ultimately led to the shop’s demise in 1939.

By Vickie Vértiz

The doors built into the cobalt blue facade of Avenue 50 Studio, adorned with a vibrant Sagrado Corazón, seem always to be open. Kathy Gallegos, director and visual artist, developed this space into a Latinx community arts nonprofit in the heart of Highland Park, launching and promoting the careers of writers and visual artists alike. Since she first opened those doors in 2000, Gallegos has grown a small live/work space into galleries, artist studios and headquarters for the multilingual poetry press and library Alternative Field. Though COVID-19 put a long pause on events, Avenue 50 is back with exhibits, tenants’ union meetings, workshops and La Palabra, a monthly poetry reading series.

Combining visual and literary arts made sense to Gallegos. When poet Rafael Alvarado approached her with La Palabra 20 years ago, “It was perfect,” she said. “Poetry inspires us to make visual art and vice versa.” Gallegos created the space to help Chicanx and Latinx visual artists who were being rejected by local museums. Gallegos knows writers face similar obstacles. Avenue 50 centers on Latinx work but has grown to celebrate other diverse artists.

By Mark Swed

When the Brentwood Country Mart opened in November 1948, on the corner of San Vicente Boulevard and 26th Street, it pleasantly provided amenities for Santa Monica and Brentwood and the nearby Pacific Palisades — low-key and relatively affordable neighborhoods at the time. As Brentwood got tonier, movie stars joined the ranks of the residents who regularly picked up groceries, had their shoes shined and mailed letters in the barn-shaped one-stop shopping complex.

Some of those neighbors also happened to be luminaries of the émigré community. Did they shop at the Mart? Yes. Did they hang out at the Mart? There is anecdotal evidence that makes that seem likely.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.