Review: A Russian oligarch isn’t the only one on the make in an eerily timely new novel

On the Shelf

Hammer

By Joe Mungo Reed

Simon & Schuster: 352 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

A novel about a Russian oligarch who wants to overthrow President Putin as the latter makes claims on Ukraine reads differently this month than it might have as recently as January. Here in March, the world watches as Russian troops bomb civilians in Kyiv and Kharkiv, streams of refugees rush across borders and Westerners speculate about dissension in Putin’s ranks.

Although Joe Mungo Reed’s second novel, “Hammer,” is set in 2013, his book’s Putin is the same man we know. He was already rattling his saber at defiant Ukraine; shortly thereafter, Russia-backed leader Viktor Yanukovych would massacre protesters in Kyiv’s Maidan, only to lose his grip on power, after which Putin thrust that saber deep into Ukrainian territory and seized Crimea.

There’s no need to speculate on Reed’s prescience. Russia has been trying to control resource-rich Ukraine ever since the country declared independence in 1991. Yet the author’s play on history takes on an eerie cast now, especially as the West’s sanctions are targeting the class at the center of his novel.

In fact, most of “Hammer” is set in London and on a handful of English country estates. That’s where many Russian oligarchs have sheltered their fortunes and their prep-schooled children, and where Reed’s oligarch has repaired with his much younger wife and his growing family of precious art.

The action begins at a busy London auction house where Martin, a junior associate, struggles to keep up with his task of bidding on behalf of a “house client:” “One must simply raise one’s paddle and speak clearly, and yet in such simplicity lie old anxieties: the voiceless cries of bad dreams, the wince of answering a roll call at a new school.” Martin, whose parents are the longest-serving tenants of a fast-deteriorating 1960s commune, rebelled against their lifestyle. He takes care with his speech, clothes and hair wax.

Wilson’s third novel, ‘Mouth to Mouth,’ is a taut, heady thriller narrated by a man who saved another man’s life and wouldn’t let him forget it.

He was also drawn to upper-class friends at York University, specifically his current roommate James, who once loved and lived with the beautiful and wealthy Russian immigrant Marina. During the opening auction of contemporary paintings, Martin spots Marina. He knows she’s married to “a rich Russian, a collector” and quickly blurts out, “My bosses are interested in your husband.”

One could write “before you know it, they’re having an affair,” but that wouldn’t be quite accurate, since there’s an auction to conduct (“the sense projected in every possible respect of elegant casualness,” Reed writes, in one of his subtler notes of foreshadowing). Even after Marina’s husband, Oleg, has spent 10 million pounds on Jean-Michel Basquiat’s “Hannibal,” there’s a lot of information and interplay to get through before the plot well and truly thickens.

On second thought: The information is the action — it is the essence of Reed’s style as well as his source of tension. What happens before the hammer comes down, be it an auctioneer’s gavel or a tyrant’s order?

“Hammer” is a many-layered slow-burn of a novel that won’t be to every reader’s taste. Not only does the story wend its way down a rambling country lane, but the road is bordered with giant hedgerows. Like would-be gawkers riding past Bel-Air estates, characters and readers alike are left desperate to know what unattainable riches lie beyond.

Everyone seems to have blinders on: Martin as he gets more and more entangled with the Russians; James, who seems determined to waste his considerable musical talent; Marina, caught between a dead-end marketing job and a dying marriage; Oleg, scheming to run for president of Russia.

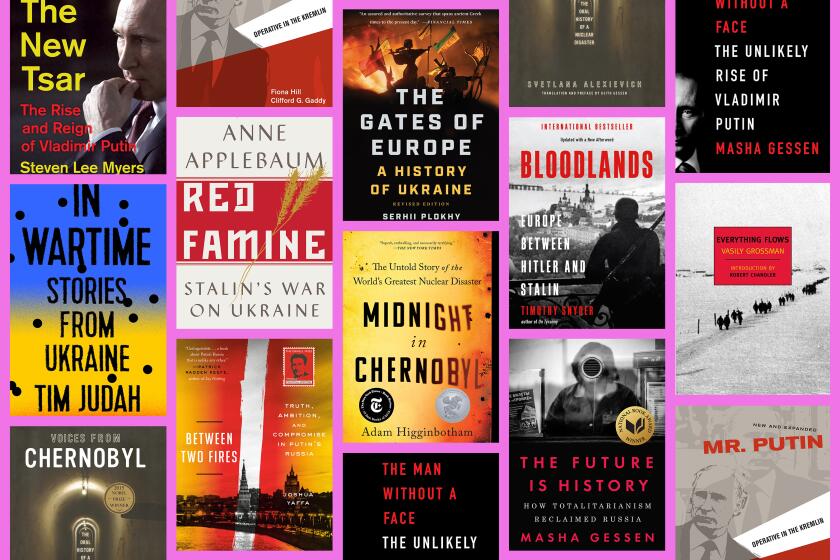

A primer on the past and present of two entangled nations at war, from histories of Chernobyl and famine to courageous chronicles of Putin’s terror.

The only characters who seem surefooted are Martin’s parents. When their commune decides to sell the gorgeous estate they’ve lived in so long, many of the members opt for cottages and condos of their own. Suddenly, Martin’s parents are planning to live in town. “’You’re there,’ says his mum, ‘and a lot of my protests are in London.’” Though still defiantly an old hippie, she has a far healthier understanding of what money can and can’t buy than anyone else in the novel.

As for the rest, they are doomed to chase after money not as a means toward happiness but a substitute for it. Marina considers, at one point, that money “means everything and nothing, and the key to having money happily is to work out how to believe both of these things at once.” Meanwhile, Martin desperately wants to believe the sale of Oleg’s prize painting, Ukrainian old master Kazimir Malevich’s “Supremus No. 51,” will gain him not only financial security but also credibility, authority and the status he thinks he wants.

Just as Marina is musing that Oleg once seemed to “have mastered the art of being rich,” we are learning that Oleg wants something different. Marina tells Martin, speaking of Oleg: “You can’t believe so truly in yourself without being a little petty, I think, without a little ignorance of your own foolishness. These men don’t doubt what they want. These men are relentless, so tiring eventually. These men can’t let a single thing rest.”

“Is that so?” Martin responds, and she says, “Believe me.”

A sanctions regime aimed at putting pressure on Russia’s wealthiest citizens has put a spotlight on the global mega-yacht trade.

Yet Oleg changes. When his mother dies and he returns to his hometown for her funeral, he reconnects with his nation and sees how poorly suited its government is for 21st-century life. Whether his new political ambition springs from his heart or his ego almost doesn’t matter. It acts as a catalyst toward the book’s denouement: Careers are made, relationships broken, the best and worst of times coming to pass.

“Hammer” is a tragedy of manners, should such a thing exist (perhaps “Les Liaisons Dangereuses”). It is also a timely document of a world in which corruption and sincerity, lofty intentions and craven pursuits, can be impossible even for the perpetrators to tell apart.

Patrick is a freelance critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.