Roberto Bolaño inspired him to write. Now Alejandro Zambra is the next Chilean breakthrough

ON THE SHELF

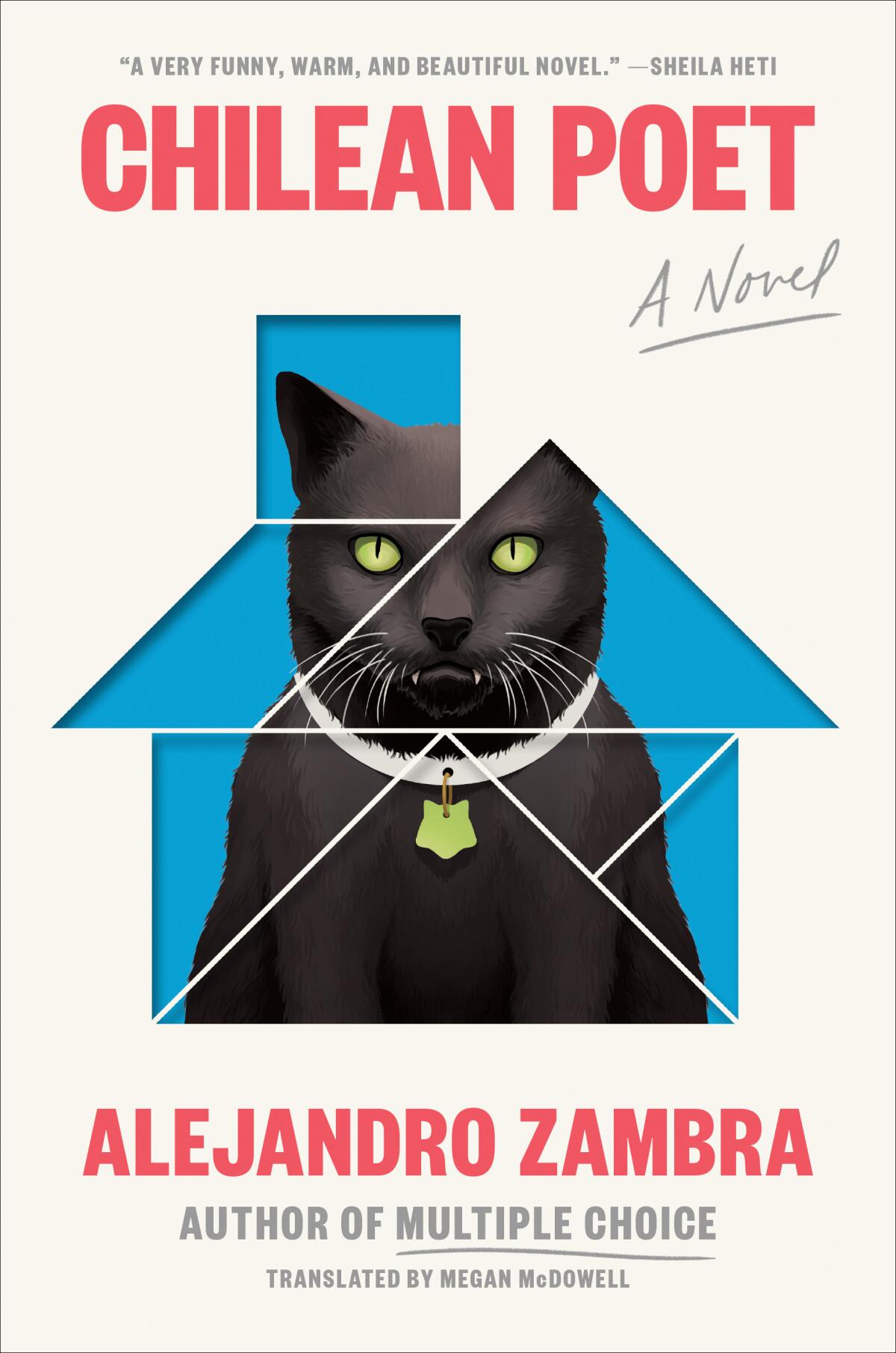

Chilean Poet

By Alejandro Zambra

Viking, 368 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Critics have likened Alejandro Zambra to Roberto Bolaño, declared him the literary heir to the late Chilean poet and novelist whose 1998 novel “The Savage Detectives,” about a radical group of Mexican poets, eventually earned him worldwide, posthumous fame.

It’s a flattering comparison, of course, but it means more to the author than you’d know. Before he read Bolaño, Zambra was entirely devoted to poetry.

“I was like the characters in my books — I didn’t read novels,” Zambra, 46, said in a recent video interview conducted in Spanish from Santiago, Chile. Before he went on to win his own awards for “Ways of Going Home,” “Bonsái” and “My Documents,” it took a writer like Bolaño to show him how prose too could be lifted from the mundane, made to sing with intensity and express humor steeped in pain.

The occasion for our interview is a new novel that broadens the author’s scope and quite likely his international reputation. Published in Spanish in 2020 and out in English this week from Viking, “Chilean Poet” is a tender and funny story about love, family and the peculiar position of being a stepparent. Also, Chilean poets.

From Boyle Heights to Filipinotown to the Autry Museum, venues are hosting poetry readings again, restoring a vital link between artists and their communities.

The story begins with Gonzalo, a teenage poet enamored with a girl, Carla, who has an obvious lack of interest in poetry. She breaks up with him early on, but years later they run into each other at a gay nightclub in Santiago. Carla is now a mother to Vicente, 6, a precocious boy who’s addicted to cat food. Gonzalo becomes a stepfather to him until his aspirations take him to New York.

The second half of “Chilean Poet” follows Vicente, now a grown-up aspiring poet himself, who meets an American journalist and convinces her to write about the everyday poets of Chile. A chance encounter eventually reunites Vicente and Gonzalo.

This is not Zambra’s first work about the stepparent relationship, one he’s familiar with as a former stepfather himself. “In this book, I thought a lot about an inherent theme of fatherhood, which is that of legitimacy,” he explained. The suffix in padrastro, the Spanish word for stepfather, is often used to form pejoratives — a construction Zambra said “punishes that role.” To be one is “to occupy a position that isn’t yours.”

It is a tricky role, which Zambra explores in his signature style, mixing tenderness, depth and laugh-out-loud humor. Lindsey Schwoeri, who edited the English-language translation, particularly loved the parts about family: “What it means to make one, to join one, to lose one,” she said. “To me, one of Alejandro’s greatest gifts is his ability to capture something ineffable about daily life, the small wounds and joys and disappointments bound up in ordinary moments.

“I laugh constantly, reading Alejandro,” she added, “even as his work causes me to feel very deeply, captures something inescapably true about living.”

Even over Zoom, Zambra embodies those descriptions in the flesh. Donning a blue T-shirt and black shorts, his hair a coal-black, messy mound on his head, the writer was thoughtful, relaxed and casual. At one point, a rolled-up cigarette in hand, he asked if he could smoke and laughed. Later he said, “I know you saw me smoking, but no you didn’t.” He indulges only in Chile, he explained. (For five years he’s called Mexico City home, just as Bolaño did for much of his life.)

Zambra talks critically and lovingly about Chile, the way a mother might describe a willful child for whom she only wants the best. He talks of the pandemic nightmare and of his son Silvestre, 4, whose linguistic explosion over the last several years has been an endless source of wonderment.

“There was one day when it seemed as though he’d spent the day eating an entire dictionary,” he said, smiling. It was a respite from the “infected and stale” discourse of the pandemic.

“I was lucky that those two moments coincided,” he said. Without a child, “I would’ve probably rewatched ‘Mad Men’ or gotten to the point where Netflix asks, ‘Are you still watching?’... He allowed me to reconnect with the mysterious.”

Writing “Chilean Poet” also reconnected the expat with his motherland. Born in Maipú, Chile, in 1975, Zambra spent much of his childhood playing in the streets. “Kids in those days were very free.”

Shrouding that fun, however, was a palpable and ominous silence. These were the years of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship, but the tension also lived closer to home. “The adults were always angry and hardly talked to each other; among ourselves there was a lot of lively discussion, but our parents barely knew each other,” he said. “There was a lot of distrust.”

Out with “L.A. Weather,” her third novel, María Amparo Escandón talks about fleeing L.A.’s wildfires, dreading the climate and loving her adopted city.

Then there was his maternal grandmother. Josefina Gutiérrez Parra, a short, plump woman with lively eyes, was “an extraordinary character” who would laugh one minute and cry the next, suddenly break into song and generally leave the kids in stitches.

It was she who encouraged her grandchildren to write. “Thanks to her, writing became a habit and still is.” Yet writing as a calling was never part of his plan; Zambra dreamed of being a musician or soccer player but wasn’t very good at either. “I was skinny but slow, and my legs didn’t do what I wanted them to.” He went on to study literature and Hispanic studies before becoming a professor and a literary critic.

By the time a grant took Zambra to New York in 2015, he’d published several award-winning short novels. The Nation had called him “the herald of a new wave of Chilean fiction” and the New Yorker christened him “Latin America’s new literary star.” In an exuberant review of “My Documents” in the New York Times Book Review, Natasha Wimmer called Zambra “the most talked-about writer to come out of Chile since Bolaño.” Wimmer should know: She was Bolaño’s English-language translator.

It was in New York that Zambra met and fell in love with Mexican writer Jazmina Barrera; they moved to Mexico City to start a family. Zambra nicknamed his tiny office in their apartment “Chile.” “I’m going to Chile,” he’d announce when it was time to work. It’s where he wrote “Chilean Poet,” channeling his impending biological fatherhood into a tale of stepfatherhood.

His relationship to his homeland also deepened and transformed. Instead of what he characterizes as his earlier “paralyzing, caricature nostalgia” for Chile — “you know, the bad kind of nostalgia that can be very corrosive” — he imbued the new novel with a more casual and realistic impression, that of a grown son awakening to his parents’ flaws and strengths.

“I think of the novel as one of those people who visits you and you fill their glass every once in a while so they’ll never leave,” he said. “There’s something in the tone of Chilean conversations that I missed and was able to recover in this novel.”

In ‘Home/Land: A Memoir of Departure and Return,’ Rebecca Mead, who returned to England after decades as an expat, asks what it means to be home.

At 350-plus pages, “Chilean Poet” is Zambra’s most substantial book. Megan McDowell, his longtime translator and close friend, also considers it her favorite.

“This is a cautiously and beautifully optimistic book,” she said. “It manages to be funny without being facile. It’s moving but still has glimmers of experimentation.”

To some readers, “experimental” is code for difficult. But Zambra’s incursions into metafiction, in which the author peeks in and winks at the reader, feel playful, serendipitous. He’s clearly having fun.

“One of the most pleasurable things about writing are the moments when you don’t know what you’re doing,” he said. “I enjoy that failure because you discover voices you had inside of you, or words that you didn’t know you liked, nuances that you didn’t know existed.”

His approach to publishing, however, is to keep it at arm’s length. “I never want to publish something out of obligation,” he said. He works on what matters in the moment. These days he is brainstorming titles for a book he’s finished but has no immediate plans to publish while working on short stories and essays. One “essay-story” is about soccer and fathers — how some show sadness only when their favorite team loses. It’s really about about fragility and frustration.

There is a tendency, in reading books set abroad, to seek political insights and lessons that might apply at home. But Zambra doesn’t write to instruct others; he writes to work out his own understanding of the places he’s lived, the people he’s known, the loved ones he’s cared for. “If we all wrote,” he said, “we’d take more responsibility over what happens to us, we’d stop f— people over as much.” If he were allowed to define his occupation, it wouldn’t be poet or novelist or essayist, but simply “human being.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.