Pedro Almodóvar’s first book, like his movies, blends reality and fiction: ‘A fragmentary autobiography’

Fall Preview Books

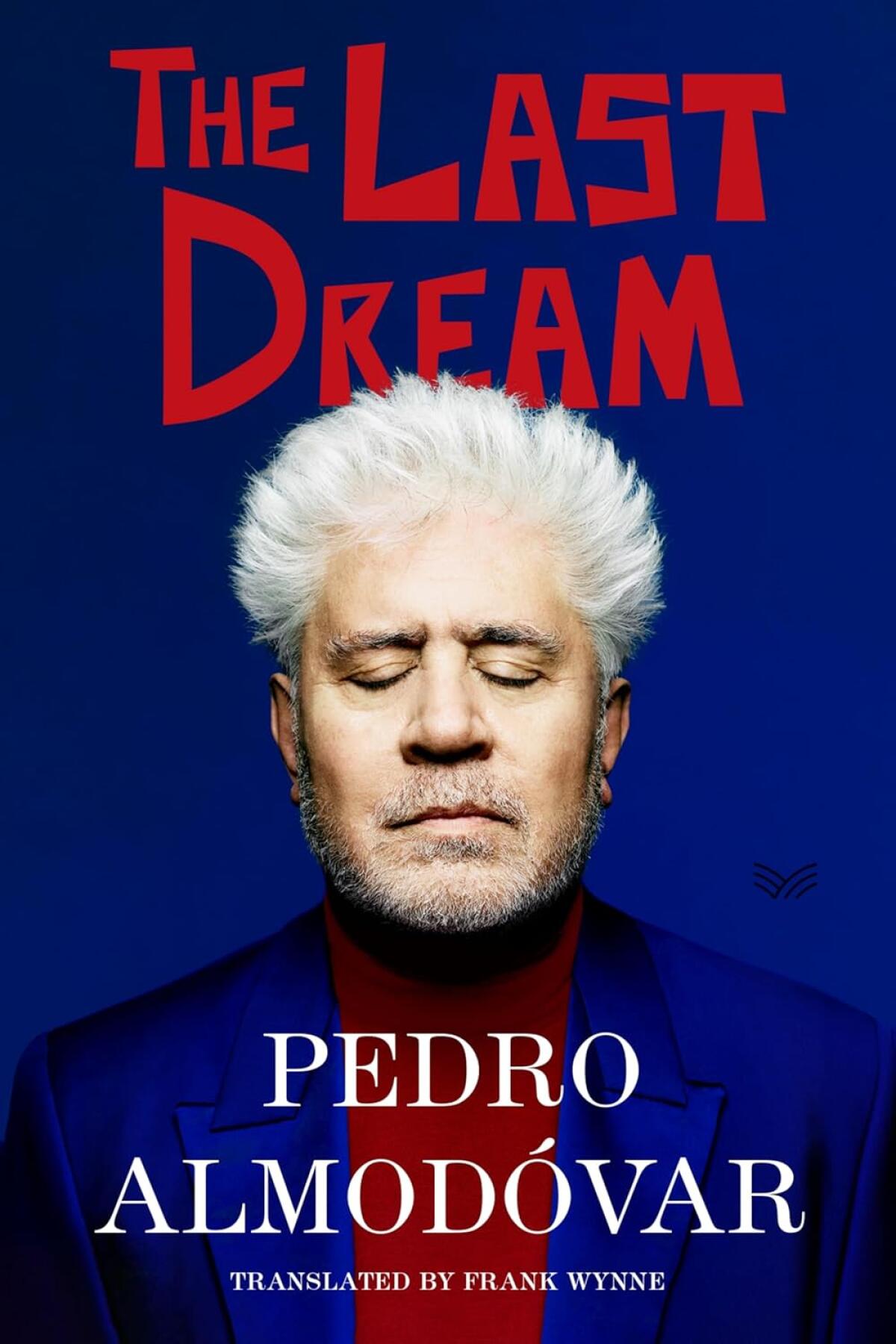

The Last Dream

By Pedro Almodóvar, translated by Frank Wynne

HarperVia: 240 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

When Pedro Almodóvar was a young boy, his mother would read and translate letters for their illiterate neighbors. One day, Almodóvar discovered that his mother was embellishing, even fabricating, what was in them.

With the irate purity of an 8-year-old, he confronted her and asked why she told one neighbor that the author of the letter had written movingly about her grandmother, a person not even mentioned in the communication.

“Did you see how happy she was?” his mother responded.

Writer-director Pedro Almodóvar’s latest film was passed over by Spain; he hopes the Oscars see it differently.

“That was a very good lesson for me even if I didn’t know it at that moment,” the Spanish filmmaker recalled in a recent video interview. Resplendent in a deep blue shirt, he was promoting his first book, a mix of short stories and personal essays called “The Last Dream.” The title piece is an essay about his mother that was written after her death.

“I soon realized reality needs fiction to make life easier and more livable,” he says, adding that it informed his stories and later his screenwriting. He always blended reality and fiction, telling personal stories without being beholden to a documentary-style reciting of the facts. (His mother also got Almodóvar a job teaching young men to read and write, which became a scene in “Pain and Glory.”)

Those stories have fueled a career that includes an original screenplay Oscar for “Talk to Her,” plus noms for his films “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown,” “All About My Mother” and “Pain and Glory.” Along the way, Almodóvar, whose movies are renowned for their vibrant color palettes and dynamic soundtracks, became an icon in the LGBTQ+ community for capturing the love — and the complex nuances — of queer characters and helped make Antonio Banderas and Penélope Cruz into stars.

Almodóvar’s book — out Sept. 24 — came about accidentally. He has always been a storyteller and started writing as a teen. “But then, as I grew older, I started experimenting with Super 8 films and discovered I had more talent for expressing my stories with images. I was better at writing for the movies than as a fiction writer.”

But he always wrote, even if he stuck the short stories and essays in a drawer. “I wrote because I wanted to,” he says. “I didn’t think about the stories being published or made into movies; I just felt the necessity of writing it.”

Eventually, his assistant, Lola García, pulled out some of the old folders and suggested that Almodóvar consider publishing them. As he notes in the introduction, he has never written a memoir, allowed for an authorized biography or even formally kept a diary. But Almodóvar found, on reading the pieces he has collected, that they amount to “a fragmentary autobiography, incomplete and a little cryptic.”

Of course, most of his films are so personal that they fill in many of those gaps. “My stories and movies are all mixed together in a kind of indivisible manner,” he says.

Antonio Banderas’ performance is the key to a soulful, personal exploration of life and film.

You might expect a director publishing his first book to stick to the writing but Almodóvar continually returns to the world of film in our conversation. He talks about having “always dreamed of writing a great novel” but finally accepting that he wouldn’t be able to while still hoping to at least write a “good and entertaining one,” then veers off into the difference between writing novels and scripts. He points to Cormac McCarthy’s screenplay for Ridley Scott’s “The Counselor,” starring Cruz, Michael Fassbender, Cameron Diaz, Javier Bardem and Brad Pitt.

“I love McCarthy’s novels, and they’re so full of dialogue so you immediately think they’d be a good script, but the rules for one are very different from the other, and it doesn’t mean the novelist can be a good screenwriter,” he says, then goes on to discuss Joseph and Herman Mankiewicz, Raymond Chandler and the ways writers do or do not adapt to Hollywood.

He also answers one question about his stories with a long explanation about how a car accident in “All About My Mother” is both an homage to John Cassavetes’ “Opening Night” and also deeply personal for him. “The movies I see, the things I read, they all become part of my own experience,” he says, “so there are many scenes in my movies that reference other movies.”

He also notes that the first story in his book, “The Visit,” later became the inspiration for his 2004 movie “Bad Education.” But it’s far from a straightforward adaptation. While the story opens with a classic Almodóvar flourish — a young woman flamboyantly dressed like Marlene Dietrich saunters through a small town before stopping at a Catholic school where she forces a showdown with the headmaster — and finishes with a dramatic plot twist, the film, with its multilayered meta examination of storytelling, is far more ambitious.

There’s something very sad about referring to Bruce Willis in the past tense, or the arrival of a book that serves as a career retrospective.

While “Bad Education” still condemns the church and the priests who sexually molested young boys and got away with it, that’s not the focal point. And the priests are even somewhat humanized.

“I wrote the story in the ’70s, and I can see my anger,” he says. “I was still furious in 2000, and I wanted to talk about the abuse but I was less interested in making an anticlerical movie than in talking about the origin of creativity and creation and how far people are willing to take a lie or a fiction. I was much more interested in sort of mixing all the different realities, including my own reality of being a filmmaker, as part of the story.”

Other stories, like “Too Many Gender Swaps,” aren’t directly connected to a specific movie, but he says they share thematic interests with his films. “You can see the origins of ‘Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown’ and ‘All About My Mother’ in there,” he says.

Almodóvar notes that while he is very much still the same person who wrote all these stories across the decades, he is also very different. “Back then, I could spend the whole night in a disco, drinking and dancing and then in the morning go straight to work,” he says. “But there’s a moment [when] you have to choose between excitement and health. I decided to be healthy, to work more than party.”

While he gave up partying, his health has remained an issue — his spine and heart conditions are central to “Pain and Glory.” (He‘s had to have spinal fusion, which immobilized part of his spine.)

“Now, I just write and make movies,” he says. This year, he’ll release his first English-language feature, “The Room Next Door,” starring Julianne Moore and Tilda Swinton. “My excitement now comes from my work. This means that I’m condemned to keep on making movies. The only thing now is whether they are good or not.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.