T.C. Boyle, prophet-satirist of human folly, is back on his chimp thing

On the Shelf

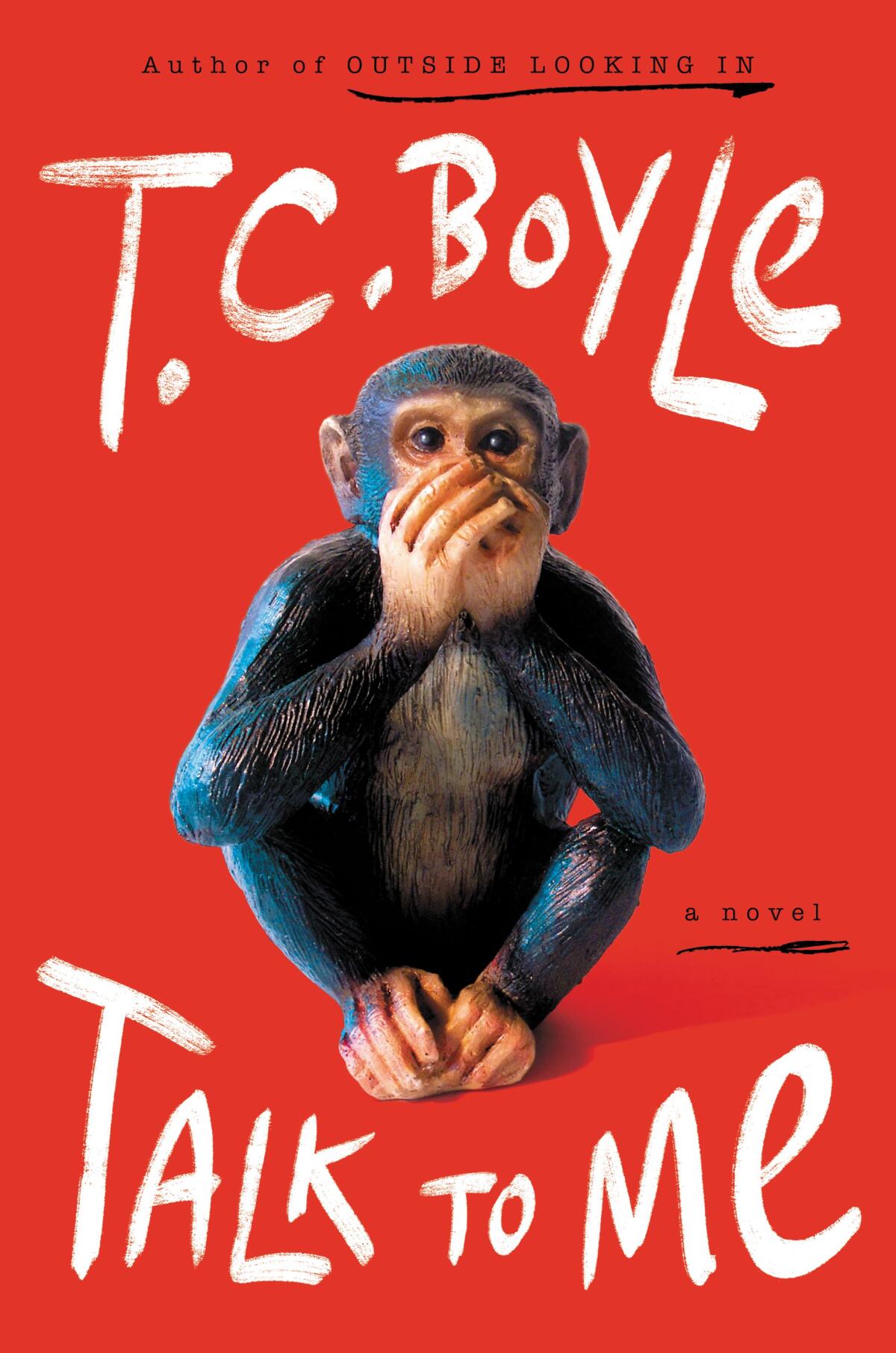

Talk to Me

By T.C. Boyle

Ecco: 352 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

T.C. Boyle’s literary career has come full circle, chimpanzee-wise.

The title story in Boyle’s first book, 1979’s “The Descent of Man,” starred Konrad, a lab chimpanzee fluent in sign language who proceeds to steal the narrator’s girlfriend. Boyle recalls its genesis via a video call from his home in Montecito, Calif.: “When I was a student in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the 1970s, I discovered that we were doing these experiments to try to teach our language to chimps. So I did this ridiculous little story about the love triangle between a researcher, her brilliant chimp and the schmuck that she lives with.”

The story wasn’t ridiculous enough, however, to put him off further tales of chimp-human relations. Konrad returned in a 1989 story, “The Ape Lady in Retirement,” in which things go very badly for both species. And another chimp, Sam, is at the center of his new novel, “Talk to Me,” tracking another kinda-sorta interspecies love triangle. A Southern California researcher, Guy, falls for an assistant, Aimee, who sees Sam as more than just a source of research funding. Sam is a devious, sometimes violent “id on wheels,” but Aimee is enchanted by his intellectual potential. “Did apes have God?” she wonders. “Did they have souls? Did they know about death and redemption? About Jesus? About prayer? The economy, rockets, space?” Interludes narrated by Sam himself at least keep the possibility open.

In this regard, Boyle, 72, is sticking with a theme that has powered much of his fiction: rationality in collision with our feral side. The premises have changed: migrants in California (“The Tortilla Curtain”), LSD experimentation (“Outside Looking In”), hippie communes (“Drop City”), so-called great men (“The Women,” “The Road to Wellville”). But explorations of good intentions pitted against human folly have been his M.O. ever since Konrad lumbered onto the scene.

Sally Rooney, Anthony Doerr, Maggie Nelson, Richard Powers, Jonathan Franzen — the list goes on. Four critics on kicking off a big, bookish fall.

Boyle set “Talk to Me” in the late 1970s, “when we were excited by this idea of communicating with other species — with dolphins, for instance, as well,” he says. “What we ignored was that other animals have their own language. Chimps have a gestural language that has got them through all these eons of evolution — until we took over the world, destroyed their habitat, put them in cages and tried to make them learn our language.”

Boyle’s view of humanity has always fallen somewhere between impishly cynical and downright grim. When his apocalyptic novel “A Friend of the Earth” was published in 2000, its vision of a 2025 rife with mass drought and epic storms seemed over-the-top. Now it seems overly optimistic. That work, along with the pandemic-themed title story of his 2001 collection, “After the Plague,” gives his oeuvre a distinct told-you-so vibe now. (In 2018 he wrote an essay for the New Yorker about the devastation of Montecito by wildfires and mudslides.)

“To me, the only thing that’s relevant to us today is this rapidly changing world, and that the conditions that allowed our species to arise are rapidly closing,” he says. “To the point which our species — a very young species to begin with — doesn’t seem to have much of a future, sad as it is to say that. But as a satirist, I have to make comedy out of this.”

If Boyle’s themes have been consistent, so too have his work patterns. For decades, he’s held to a steady rhythm of productivity. Write a novel; write a batch of short stories while preparing the novel for publication; write another novel, then another batch of stories to complete a collection. Living in California all the while, he retired from teaching fiction at USC five years ago. (“I still have my day job, though.”)

Lydia Millet, whose latest novel, “A Children’s Bible,” tackled climate change, reads new fiction on climate and argues against calling it a genre.

He’s also retained the same agent throughout his career: Georges Borchardt, a nonagenarian eminence who’s represented Elie Wiesel and Samuel Beckett. Early in Boyle’s career, Borchardt says, he saw his client as a European-style experimentalist writing in an American grain, a less weird Robert Coover. These days, he just admires Boyle’s ability to keep generating ideas. “I’m more impressed with the fact that he’s been able to write over 200 short stories, and each one is really different from the others,” he says.

Consistency can be both boon and bane, Borchardt notes. Among major American literary authors, only Joyce Carol Oates seems more prolific. (A Boyle short-story collection, “I Walk Between the Raindrops,” is slated to come out next year.) With a narrow range of prestige outlets for stories and festivals looking to mix up their headliners, Boyle occasionally has to wait his turn. Shortly after COVID-19 hit, he wrote a satirical story, “The Thirteenth Day,” set on an isolated cruise ship. Borchardt cautioned Boyle to shelve it, arguing that it was too soon to poke fun at a killer virus. “My role is to do what he wants,” Borchardt says. “I don’t decide to hold back on something — I suggest doing it.” Still, Boyle acceded; the story will appear in Esquire early next year.

“It’s never happened to me before,” Boyle says of the story’s two-year delay. “But, extraordinary times.” He can afford to be patient in part because his audience has expanded well outside the United States. In America, Boyle has never quite achieved the status of a literary titan — no book of his has been a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award or National Book Critics Circle trophy. (He has, however, won The Times’ Robert Kirsch Award for Lifetime Achievement.) Yet in Germany in particular, he enjoys both sizable esteem and sales. The title of a 2019 documentary about him makes the point crystal clear, even if your German is rusty: “T.C. Boyle: Rockstar der amerikanischen Literatur.”

Author events for him in Germany can attract up to 1,500 attendees, says Christina Knecht, publicist for Hanser, Boyle’s longtime German publisher. As the pandemic upended travel and publishing schedules, “Talk to Me” ended up in the peculiar position of first appearing in German translation last January. A digital reading tour for the novel, Knecht says, attracted around 3,000 attendees paying 10 euros each to tune in.

Novelist T.C. Boyle discovers sanctuary as the caretaker of a Frank Lloyd Wright home.

“Germans are very interested in American culture, and he’s part of American pop culture,” Knecht says. “When you meet him, you notice at once that it’s not an attitude — he’s a cool person. He’s very relaxed with everything. I guess he has a good life.”

Whatever the vicissitudes of his reputation, Boyle is in no danger of running out of subject matter. The disruptions of COVID-19 are only fodder for more fiction. What could be more Boyle than a pitched, bloody battle between a wily virus and an outsmarted populace? America in 2021 is plainly on-brand.

“As we learn from the scientists each day with the mutations of the virus and the variants that are being produced by the factory of the anti-vaxxers and the morons out there, this may be the new way of life for us for a long time to come,” Boyle says. For the immediate moment, though, his main concern is climate change; it’s the subject of a new novel-in-progress, tentatively titled “Blue Skies.”

“[The title is] slightly ironic, as you can imagine,” he says. “If it had a subtitle it would be ‘Nature Bites Back.’”

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

Maggie Nelson, whose essays and poetry have changed the way we think about art, queerness and gender, talks about her timely new book, “On Freedom.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.