T.C. Boyle’s new novel takes a trip with LSD evangelist Timothy Leary

T. C. Boyle’s house is surprisingly accessible behind a waist-high slatted wooden fence in Montecito, just south of Santa Barbara. But once you get past the front gate (without a “Tortilla Curtain”-like guardhouse in sight), you enter the sort of marvelously incomparable landscape that is usually only available in one of Boyle’s books.

Then, sounding like one of Boyle’s druggier characters, I say the first words that come to mind: “Oh, wow. I mean, just, you know, wowww.”

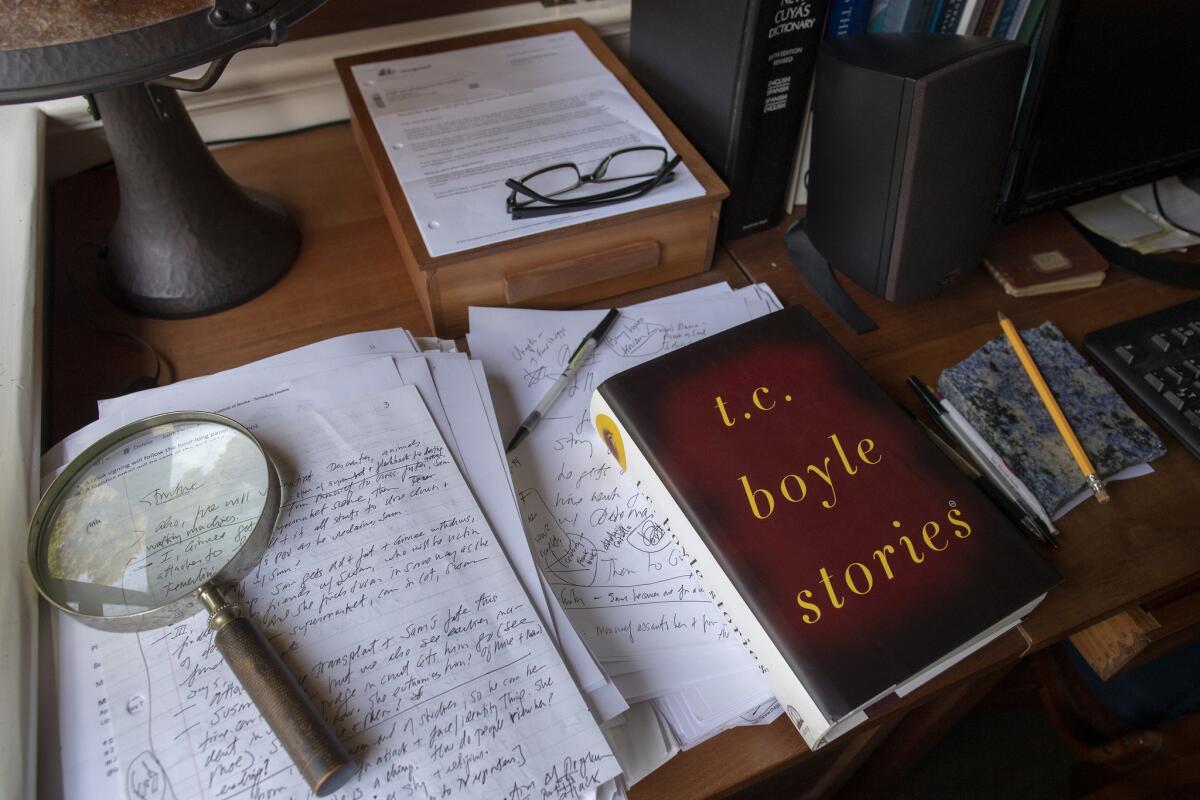

I’ve been reading and enjoying Boyle’s ineluctable production of widely various stories and novels for decades now and it’s almost a relief to find myself immersed in all this panoramic splendor – lots of shining redwood and ceiling-high windows. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1909, Boyle’s house — like Boyle’s fiction — is so open to the world that it’s hard to tell whether you’re outside looking in or inside looking out.

“My wife and I found it 27 years ago,” Boyle tells me, “and we just had to buy it — the only one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie style homes in California. Wright believed that the subject of a house should be the environment around it, and wherever you sit and in whatever direction you face, you’re always observing the natural world.”

In Boyle’s house, it’s all museum-like control and balance encircled by the world’s uncontainable (and often terrible) vastness — a perfect home, in fact, for a self-described “environmental” novelist concerned with what we animal-like humans can control about our lives (not much) and what we can’t (everything else). Boyle has relentlessly explored these conflicts in novels such as “The Terranauts” (2016), about eight disparate people trying to live together in a self-sustaining eco-sphere, or the now classic “The Tortilla Curtain” (1995), in which affluent residents of a gated community grow increasingly dependent on the immigrants they are trying to keep out. Then, of course, there is the inescapably pertinent “The Women” (2009), concerning the messy emotional life of Frank Lloyd Wright during the years when he was creating beautifully unmessy environments like this one.

Which, by the way, answers one really boring question not to ask a prolific writer: “Where do you get your ideas?”

Because the answer is obvious: They get them from where they live.

ALSO: Bret Easton Ellis is over today’s Trump obsession — in ‘White’ he finds other targets »

In the 1980s, when I was reading Boyle’s early short-story collections — “Descent of Man” (1979) and “Greasy Lake” (1985) -- I was often surprised to find him described as “wacky,” “hilarious” or “comic.” For me, Boyle writes “realistic” fiction, though, granted, it describes a world of human folly that makes you laugh out loud. He always places his readers in the shoes of socially disparate people — such as the Manny Mota-like miracle-man pinch-hitter in “The Hector Quesadilla Story,” or the loser-something young woman in “She’s the Bomb” who can’t pass her English course because of an aversion to “The Scarlet Letter,” and ends up issuing anonymous bomb threats at graduation.

Like the great 19th century naturalists such as Theodore Dreiser or Emile Zola, Boyle writes fiction as if he is conducting a laboratory experiment — testing how each of his characters responds to various events or conditions. Each fiction feels like an experiment in reality rather than a fabulist flight from it.

I’m on a quest here, trying to examine what it’s like to be an animal on this mysterious planet in which there is no purpose and we don’t know anything.

— T.C. Boyle

Meeting Boyle fills me with this same weird sense of juxtaposition. After living with his book jackets for half a lifetime – with all those flamboyantly coiffed and punk-stylish author photos – Boyle is soft-spoken by comparison. A tall, angular, fair-skinned man in a wool pullover cap, he’s the sort of friendly, unassuming guy you might meet hiking the canyons of the Hollywood Hills. In fact, I’m a bit surprised to hear him say: “I love being on stage, I love doing interviews, and I love doing face-to-face.” But that brings us back to the subject that seems to most concern Boyle: control.

“There’s a story I like to read at large events called ‘Chicxulub,’ a very grim story, and whatever the crowd, there’s a point in that story when nobody moves, and I can’t see them out there in the darkness but I can feel them. Nobody coughs, nobody moves a chair, and they’re horrified, and I realize that I’m horrifying them.”

“I love that feeling of control,” he continues, “and of giving readers – especially young people who might not have enjoyed fiction – the same thrill I received when, back in junior high, I heard stories read out loud by my English teacher, Mr. Grant.”

FULL COVERAGE: Read more about the writers who featured at Los Angeles Times’ Festival of Books. »

It’s a notion of control that makes perfect sense to any lover of short stories – finding that perfect opening situation that draws you in, developing a sense of intensity or peril, and then bringing it all home to a suddenly inescapable conclusion you never expected.

For it is simply impossible to find your way out of a Boyle fiction until Boyle himself shows you the door.

Boyle’s excellent new novel, “Outside Looking In,” presents his latest fictional exploration of how people drive, and are driven by, their environment. In this case, the environment isn’t a biologically diverse island off the coast of Santa Barbara (“When the Killing’s Done,” 2011) or a ’90s-era eco-sphere – rather it’s Harvard graduate school in the early 1960s. The protagonist, Fitz Loney, working toward a doctorate in psychology, suffers the usual cultural depredations of most graduate students everywhere – no money, endless days of all study and no play, a frustrated overworked wife and dull-as-dishwater faculty meetings. So when Loney is offered an alternative, he chooses a charismatic young professor named Timothy Leary, who arrives on campus with barrier-breaking attitudes about student-advisor relationships, and beaucoup doses of a new experimental clinical drug called lysergic acid diethylamide, “synthesis number 25.”

Originally developed by Albert Hoffman in Basel, Switzerland, in 1943, LSD-25 began as a clinical-trial drug for treating mental illness and, in Leary’s hands, soon became a treatment for almost every conceivable type of psycho-sexual disorder – including general social malaise. Under Leary’s tutelage, Fitz and his wife explore wide new avenues of experience: open sexual relationships, communal living, the psycho-biophysical perception of God, and escalating encounters with local law enforcement – who don’t like these weird new neighborhood parties one bit.

I’m always interested in a strong leader or a guru who says to you: ‘Give me all of yourself and I will redeem you.’

— T.C. Boyle

Soon Fitz is trading in his traditional behaviorist textbooks for the novels of Herman Hesse, and his research questionnaires for wraparound Polaroid sunglasses, deciding that his doctoral thesis is “just a distraction from the inner life, the only life that counted, and beyond that, from love. Erotic love and agape too, which were indistinguishable if you went deep enough.”

Meanwhile, Leary operates like a drug dealer – doling out free “tastes” of the merchandise to newbies, and opening his doors and pizza boxes to anyone who joins the party. After all, if you have a choice between researching at the library or partying with your prof and a bunch of attractive young people over cold martinis and hot hallucinogenics, well. It’s a no-brainer, right?

“Terranauts” — move over. It’s time to make way for Leary’s Psychonauts.

“I’m always interested in a strong leader or a guru who says to you: ‘Give me all of yourself and I will redeem you,’ whether it’s religion, or this bogus crap in Washington D.C., or Leary or Kinsey,” Boyle says. “I always wonder about what the ultimate cost is to the followers.”

The real-life figure of Leary was what attracted Boyle to this fictional story of ’60s “alternative consciousness.”

“When I was growing up,” Boyle explains, “Leary was this preposterous clown on television, wearing a toga, but now I look back and see him as this charismatic and hot young Harvard professor who just got carried away, and the drug just ate him up.”

Boyle continues: “I also wanted to explore psychedelics and theogens as allowing you to open up and see God as an aspect of brain chemistry, as if all these religious experiences people have been reporting over the centuries might well have come to us from psychedelic experience.”

As Boyle shows me out, it’s hard not to notice that this house is designed, like many of Wright’s houses, around a central fireplace; and this is fittingly where Boyle assembles his many books and international translations, displayed in large glass-paneled bookshelves, and lined up in minty first editions across the mantelpiece. It is the central node of control in a Frank Lloyd Wright home – an aesthetically satisfying space. On one end table there are recent issues of the New Yorker featuring Boyle’s latest stories, and not a hint of another author in sight – just T.C. Boyle all the way. “It’s the place I come to at the end of a day of writing to feel inspired,” he says, and like his fiction, Boyle is slightly kidding and not kidding at all. It’s another fragile zone of control in an uncontrollable world – especially when you consider the wildfires of two years ago that almost burned this house to the ground, or the subsequent mudslide that washed away houses on either side and took many of Boyle’s neighbors with them.

The recent global climate catastrophes were foreseen as far back as the 1990s, Boyle recalls, when he wrote one of his darkest novels about eco-warriors battling to save the planet in “A Friend of the Earth” (2000) – prognosticating much of the atmospheric turmoil occurring around us — and nearby Boyle’s home today. “I don’t consider myself a predictive writer,” Boyle says. “I just open my ears and hear what’s being said.” Even when a Boyle fiction leaves its reader with a sense of aesthetic pleasure – its vision of the perilous world doesn’t always make them happy.

ALSO: 5 debut novelists you won’t want to miss at the L.A. Times Festival of Books »

“My stories and novels are always dark, that’s my view of life, I’m sorry, I’d like to have better news” he says. “Other writers want to make you feel good, but I want to make you feel bad – but good aesthetically. I’m on a quest here, trying to examine what it’s like to be an animal on this mysterious planet in which there is no purpose and we don’t know anything, whether it’s science or religion, it’s all equally voodoo. What are you gonna do?”

Like his fiction, Boyle’s house stands in the confluence of forces that are greater than it is, and there’s not much you can predict about such a world. But one future is certain; with Boyle already working on his 29th and 30th books, he’s definitely going to need a bigger fireplace.

::

By T. Coraghessan Boyle

Ecco; 385 pp., $27.99 T.C. Boyle at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books: Boyle will appear at 2 p.m. Sunday following an introduction by L.A. Times Executive Editor Norman Pearlstine.

Bradfield is a writer whose novels include “The History of Luminous Motion” and “Dazzle Resplendent: Adventures of a Misanthropic Dog.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.