On the Shelf

While Justice Sleeps

By Stacey Abrams

While Justice Sleeps

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Who knew competence could be so electrifying? “I love Stacey Abrams because she gets things done,” a friend told me as I was preparing to write this article. Except she didn’t use the word “things.”

For the record:

5:26 p.m. May 13, 2021An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Fair Fight directly registered voters — it mobilized newly registered voters — and mis-stated the last name of the protagonist of “While Justice Sleeps.” It is Keene, not Steele.

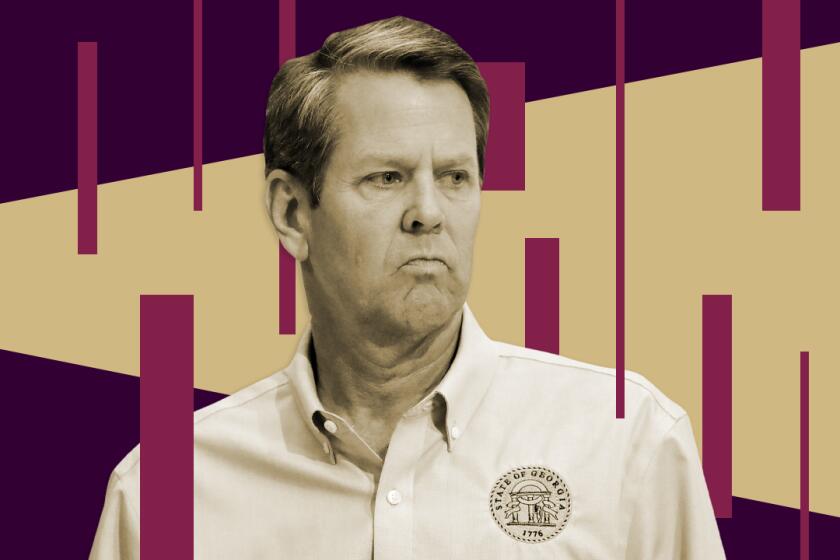

A lot of people on the left feel the same way. After Abrams narrowly lost the 2018 Georgia governor’s race to Brian Kemp, in part thanks to restrictive voting laws Kemp had implemented as secretary of State, she set about not to capitalize on her new fame but to fix the problem. In the next two years, the voting rights organization she started, Fair Fight, mobilized around 800,000 newly registered voters in Georgia, many of them from Black communities.

It was the kind of hard, detailed political work you can’t perform on Twitter. It paid off on a national scale. On Nov. 3, Joe Biden carried Georgia by scarcely 10,000 votes. Six weeks later, Abrams came through again: Democrats Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock swept a pair of Senate runoffs, defeating two heavily funded incumbent Republicans and handing the party 50-50 control of the Senate.

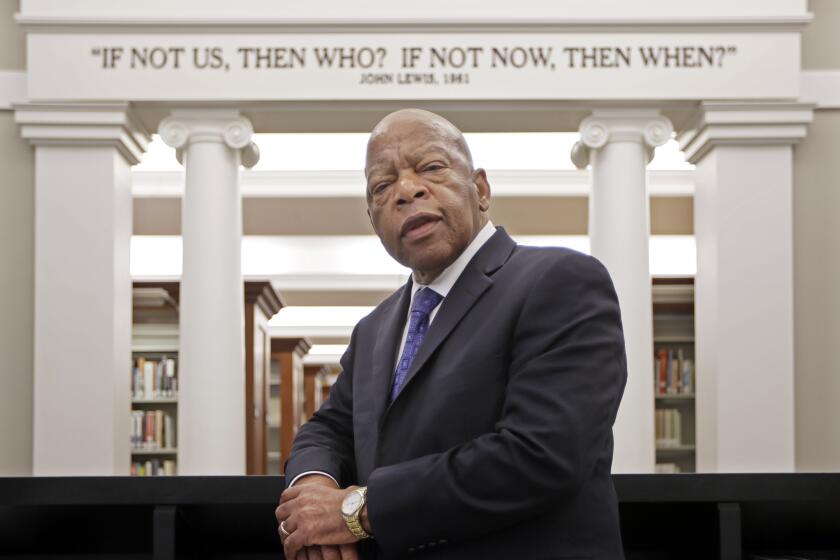

The highest office Abrams has held in government is minority leader of the Georgia House of Representatives. But in important ways, her work led directly to Biden’s ability to pass a $2 trillion stimulus package in March and possibly even pass HR1, the sweeping voting rights legislation named for the late Georgia Congressman John Lewis. This record has made Abrams, along with Katie Porter, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Elizabeth Warren and others, the face of the reborn left — tough, pragmatic, even-keeled, results-oriented.

Studios, which have previously threatened boycotts of filming in Georgia over legislation, have been largely quiet over new election rules. Why?

What relatively few of her new fans may know, however, is that before politics swept her up completely, Abrams was also a writer, the author of eight well-received romance novels under her pen name, Selena Montgomery.

For a while, that fact was little more than a fun trivia question in a bar quiz. Now, though, the publisher Berkeley has announced plans to reissue the first three Montgomery books. And this week, with the publication of “While Justice Sleeps,” an intricate, fast-paced legal thriller under her own name, Abrams steps squarely into the spotlight as a writer of fiction. With the novel acquired Tuesday for a TV adaptation and sequels in the air, she has no plans to leave that spotlight. Could a novelist make it to the White House?

In conversation, Abrams is warm, funny, curious and unpretentious, though also precise, giving answers of a legal clarity. (She wrote the first Selena Montgomery book while still a student at Yale Law School.) After 10 minutes, I wanted to be lifelong friends with her, which is of course a reaction the best politicians are famous for inducing. Yet she reminded me more of the writers I’ve met through the years: a chatty listener.

Abrams grew up in a house full of readers in Gulfport, Miss.. Her mother was a college librarian. “If you could reach it, you could read it,” she says. (Abrams and her five siblings still have a book club to this day.) As a child, Abrams loved “The Phantom Tollbooth” by Norton Juster and pored for hours over the volumes of the family’s Childcraft Encyclopedia and a book of her mother’s filled with myths, tall tales and anecdotes, whose title and author she’s tried without success to identify. Her father, who worked in a shipyard, “was dyslexic, but he was also the family’s chief storyteller,” Abrams said, spinning out long, fantastical tales she described as “lighter versions of ‘Game of Thrones.’”

Abrams was a very good student. In high school in Georgia — where her parents moved to study at Emory — she grew to love writers like James Baldwin and Bharati Mukherjee. She started her first book when she was 14, a volume with the unimprovable name “My Diary of Angst.”

Former U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey always wrote of public pain and private struggle. Her memoir, “Memorial Drive,” lets her mother speak.

But it was in politics that Abrams was a prodigy. After she organized a protest against legendary Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson for his response to the Rodney King riots, Jackson was so impressed that he hired her. Soon she was a rising star, in 2007 winning an open seat in the statehouse in Atlanta. By 2018, when she became the first Black woman nominated to run for governor by a major party in the United States, she had been fighting for voting rights in Georgia most of her adult life.

On the eve of last year’s election, though, Abrams was scrupulously reworking “While Justice Sleeps.” Her drive calls to mind Avery Keene, the novel’s heroine, a clerk on the Supreme Court who has too many problems — she’s broke, with a mother addicted to drugs — to save the world. Unfortunately, the world sometimes needs saving.

The book is a canny, closely-plotted legal thriller in the early Grisham style. It begins when Howard Wynn, the swing justice on the Supreme Court, falls into a vegetative state. The timing is suspicious: he has just delivered a scabrous attack on the smooth-talking President Stokes. (“The common touch had supplanted common sense,” Abrams writes. Choose your own president to think that line’s about.) Wynn’s enigmatic last words, involving chess and an international scientific conspiracy, are left in the care of the only clerk he holds in any esteem — Avery.

Like the protagonists in many Selena Montgomery novels, Avery is a smart, resourceful Black woman facing long odds. Abrams has said it’s the kind of character she wants to see more often in fiction — “as adventurous and attractive as any white woman,” in her words. The difference is that the Montgomery books fall into the genre of romantic suspense; Abrams told me she made them romance novels in part because women weren’t publishing much pure suspense fiction 20 years ago. (Things have improved only marginally since then.)

Rachel Howzell Hall’s new novel, “And Now She’s Gone,” breaks the crime-fiction mold; its success proves a long line of publishers wrong.

When I tried to draw her out on the relationship between her writing and politics, however, she was diffident. They’re her passions, a fact she doesn’t seem to query; the angst is gone. It was refreshing, this mature unwillingness to conflate self-mythology with introspection. It reminded me of her decision to abjure the multiple chances she had to run for Senate (or indeed, the suggestions that she run for president) after 2018. Perhaps it’s no accident that women like Abrams, Warren, Porter and Ocasio-Cortez have emerged as leaders recently; locked out of politics for so long, they don’t treat it as a personal psychodrama, in the dubious tradition of LBJ and Bill Clinton and James Comey, but as a job. In a way — allergic to cant, in love with facts, bearing whiteboards and willing to work hard — they offer a corrective to the feral romanticism of Donald Trump’s hardcore supporters.

Given this defining pragmatism, it should surprise no one that Abrams the novelist is, by her own description, “definitely a plotter.” That goes for her literary career too. She has written sections of children’s and YA books, is excited about the Berkley reissues and has plans for (spoiler alert) another Avery Keene book.

She’s less committal about whether she will ever run for president — not out of classic “Meet the Press” coyness, I think, but because in both writing and politics her signature characteristic is patience: Having seeded Georgia with voters and her writing career with books and ideas, she has waited out the seasons to see them bloom.

Abrams’ drive calls to mind Avery Steele, the novel’s heroine, a clerk on the Supreme Court who has too many problems to save the world. Unfortunately, the world sometimes needs saving.

When she was 17, Abrams set up a table at Spelman, where she had just begun college, to register voters. As important as books were in her childhood, politics and protest were central; her father, the family storyteller, had once been arrested outside the Hattiesburg, Miss., courthouse doing the very same thing —registering voters. He was 14.

“I have a goal that will never be achieved,” Abrams said when I asked her about what larger vision lay beneath her local focus. “I believe in the eradication of poverty.” She paused for a moment. “But I’ve met people.”

What becomes clear in talking to Abrams is that justice is her lasting fixation. Some of the articles about her novels express wonder that she’s so adept in such seemingly separate vocations. But reading “While Justice Sleeps” or listening to Abrams discuss how her second organization, Fair Count, is planning vaccinations, you find the same person. In a very real and non-mystical way, her politics and her writing are continuous, not conflicting.

Both professions, after all, are different ways of trying to figure out and solve the world. In a surreal moment in her nonfiction bestseller “Our Time Is Now,” Abrams recounts being denied her own ballot in 2018 when she was one of the candidates for governor. They told her she had already voted absentee, which was incorrect. True to form, Abrams found out what the problem was, fixed it and went into the booth to cast her vote.

John Lewis, an icon of the civil rights era and a longtime member of Congress from Georgia, has died.

Finch’s novels include the Charles Lenox mysteries.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.