Review: Mariah Carey’s memoir is her best performance yet

In a passage as candid as it is obvious, Mariah Carey’s new memoir details the performer’s artifice. “You build up and put on, you strategize, manipulate, accommodate, and shape-shift,” she writes in “The Meaning of Mariah Carey,” co-written by veteran editor and “image activist” Michaela Angela Davis. “It requires rituals (sometimes in the form of bad habits) to return yourself back to yourself.”

On the Shelf

The Meaning of Mariah Carey

By Mariah Carey, with Michaela Angela Davis

Andy Cohen: 368 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There are few celebrity rituals as passage-marking as releasing one’s memoir, and only a handful of such books are worthy of ceremony. “Meaning,” in fact, is, and it’s also unusual. It’s a rather self-conscious dressing-down of its subject, so meticulous as to make it seem that taking off the persona is just putting it on in reverse. If you think of the superstar diva’s career as a narrative that is cinematic in scope, this book is the director’s commentary.

The previously tight-lipped pop star connects dots from her life to her music as she never has before, weaving her lyrics in and out of relevant scenes, and sheds light on the real-life origins of eccentricities that practically ooze out of her pores under glaring studio lights. Carey’s Christmas fetish, her insistence that she’s “eternally 12,” her strong preference for performing in fan-generated wind tunnels — many of her quirks are carefully sourced. If she is over the top, here’s a book-long theory of how she got there.

A discriminating reader may question whether this book is laying Carey definitively bare or merely reinforcing a painstakingly crafted public image. But what Carey and her co-writer have assembled is such a terrifically readable yarn that the warts-and-some treatment feels impressive either way. It is, above all else, an exceptional entry in the genre.

Christmas has come early for Mariah Carey: the pop star’s original holiday classic, “All I Want for Christmas Is You,” has reached the No. 1 spot on the Billboard Hot 100 chart 25 years after its release

Carey’s life story has the sweeping arc of fiction: a literal rags-to-riches tale that turns into a poor-little-rich-girl dirge, then cascades into self-actualization and artistic emancipation. “I had no frame of reference for normal,” writes Carey. What sounds tough to live through is riveting to read about. Carey grew up in various homes around Long Island (including one she calls “the shack”) as the child of an interracial couple who split when she was very young. She details a series of mistreatments, mostly at the hands of her neglectful mother and her older sister, Alison, whom Carey alleges offered her cocaine, attempted to pimp her out and threw a scalding cup of tea on her that required a doctor’s care. Carey was 12.

She found little comfort outside of her house as a biracial kid who was frequently the object of her classmates’ bigotry: A particularly harrowing anecdote recounts Carey being invited to a peer’s Southampton home only to be locked in a room and called the N-word by a group of white girls.

But Carey was a gifted child, and her singing was encouraged (sometimes irresponsibly) by her opera-diva mother. She moved to New York, became a session singer and was signed at 18 by Sony after giving its boss, Tommy Mottola, a demo tape. Mottola soon started wooing her romantically, and Carey writes that their ensuing marriage effectively imprisoned her. Sing Sing was her name for their sprawling estate in upstate New York, which Mottola decked out with security cameras and armed guards. Carey recounts Mottola’s constant surveillance, controlling nature, and “unpredictable” rage. She writes that he held a butter knife to her face in front of a group of guests at their home, furious over her desire to break things off.

Then, just as in her childhood, music was Carey’s saving grace: “I smuggled myself out bit by bit, through the lyrics of my songs,” she writes. In a series of vivid anecdotes that unfold with tension and poignancy not typically seen in celebrity writing, Carey shows what she tells: A trip to Burger King with her rapper collaborator Da Brat provides a 20-minute respite from Mottola’s emotional abuse; her brief relationship with Derek Jeter, bonding over their shared biracial identity, showed her what life could be after Mottola. A stolen moment with Jeter, kissing in the rain, provided the basis for what she calls her first complete docu-song, “The Roof,” from her acclaimed 1997 album, “Butterfly.” The way experience glided into music is so poetically rendered that a song could be written about the making of the song.

Princeton University professor Sean Wilentz has never had any trouble seeing Bob Dylan as a crucial literary figure.

Carey’s established persona translates well in her prose. Idiosyncrasies abound: her proclivity for 10-dollar words that pepper her plainspokenness with bits of humorous formality (“gallivanting,” “delegation,” a house that smells of “calamity and dog hair”); her love of “moments” (“Farrah Fawcett layered moment” is how she describes her hair in a video); her tendency to punctuate statements with “dahling.” These are felicitously doled out, making the book voicey without congealing into shtick. She is frequently funny, never more so than when refusing to print Jennifer Lopez’s name, instead referring to her rival as “another female entertainer on [Sony] (whom I don’t know)” — a winking reference to the definitive meme of diva shade, a 2003 interview in which Carey was asked about Lopez and responded, “I don’t know her.”

Carey knows when to withhold for effect, but she also deprives readers thirsty for tea. There’s no mention of Eminem, with whom she associated briefly, after which the pair volleyed diss tracks for years. She doesn’t discuss her bipolar diagnosis, received in the wake of her disastrous “Glitter” project, as she told People in 2018. (She does refer to a therapist calling her behavior somatization.) Mottola aside, her breakups are usually summed up in vague sentences that come down to: It just didn’t work out.

Carey’s music took a decidedly R&B turn when she gained the courage to defy Mottola; early on, Carey writes, “he tried to wash the ‘urban’ (translation: Black) off of me. And it was no different when it came to the music.” She says Mottola “smoothed out” her sound, though she has always contended that she’s the primary architect of her work, a musician whose contributions to her art beyond her prodigious singing have largely gone unsung. Some clarity on her collaborative process could have solved this seeming paradox, and lent Carey’s character some welcome depth via accountability.

Instead, she presents as an angelic self-portrait, someone who has made a life of transubstantiating pain into joy. In so much of the book — her childhood and the Mottola years take up about two-thirds of it — she casts herself as, above all things, a survivor of hardship. Much of the focus is not on what she has done but what was done to her. Reacting defines her persona and the cultural m.o. of her memoir. This book sets in type pop music’s ethos of good packaging. To love pop is to appreciate its gloss, and in that narrow but all-important sense, wow does “The Meaning of Mariah Carey” shine.

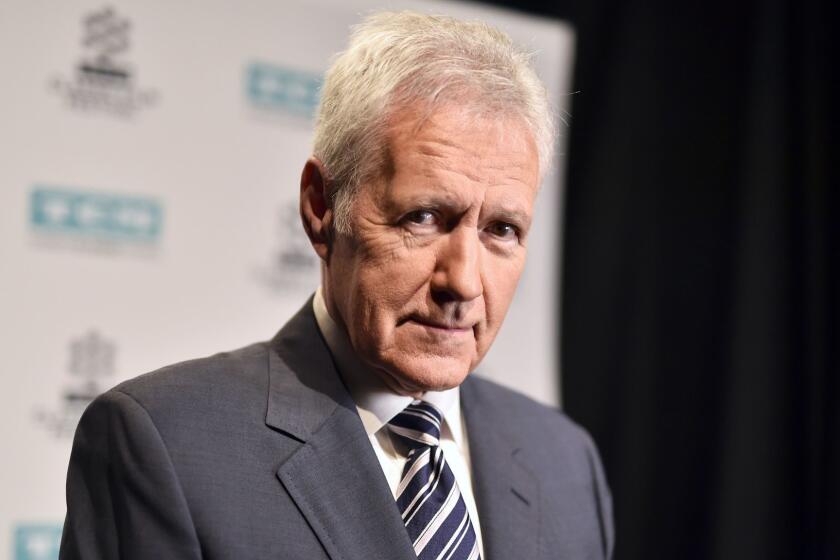

Alex Trebek is happy being an uncle figure in your life, and he’s not afraid to describe cancer’s personal toll. He sits down to talk about his memoir, “The Answer Is ... Reflections on My Life.”

Juzwiak is a senior writer for Jezebel and co-writer of Slate’s “How to Do It” advice column.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.