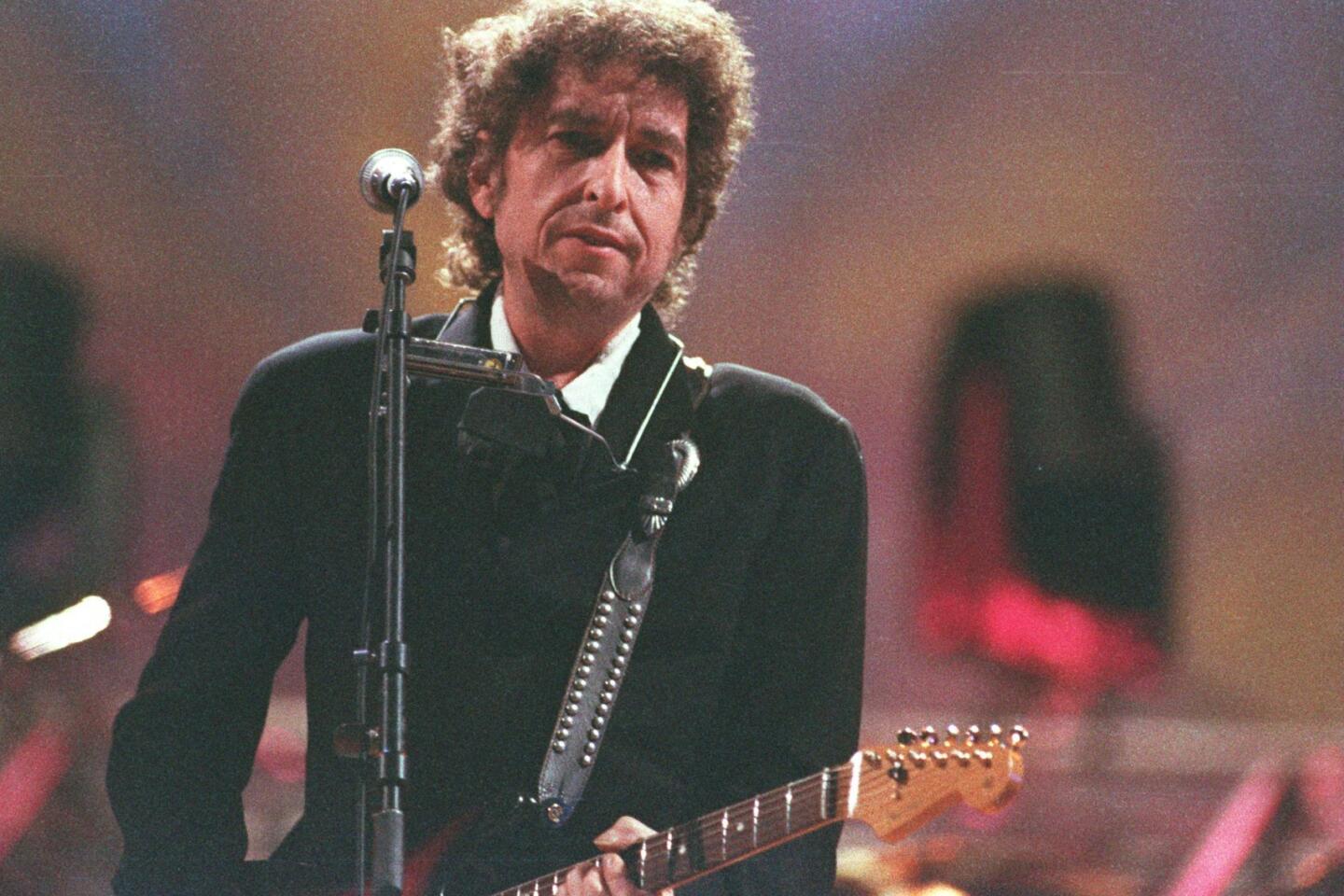

‘He’s a historical magician’: Two professors on why Bob Dylan deserves the Nobel Prize

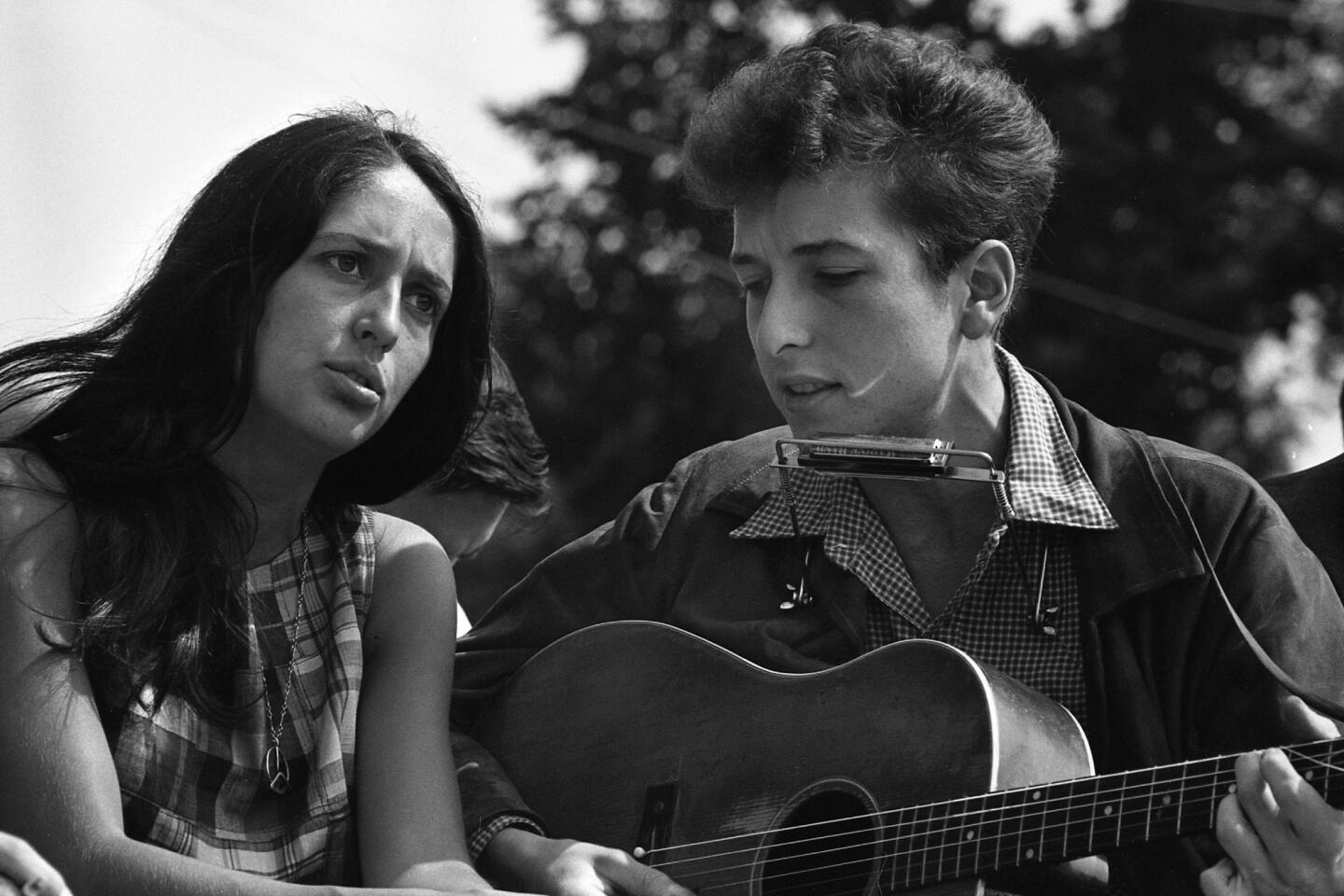

Princeton University professor Sean Wilentz has never had any trouble seeing Bob Dylan as a crucial literary figure.

“He’s a historical magician — a writer who’s capable of creating this zone where it’s 1935 and 1835 and right now and tomorrow,” said Wilentz. “That’s his genius.”

But the author of “Bob Dylan in America” concedes that not everyone in the academic establishment has always viewed the 75-year-old songwriter that way.

“Because he comes from the world of popular music, there’s been some hesitation,” Wilentz said. “In some circles, he had to be legitimized.”

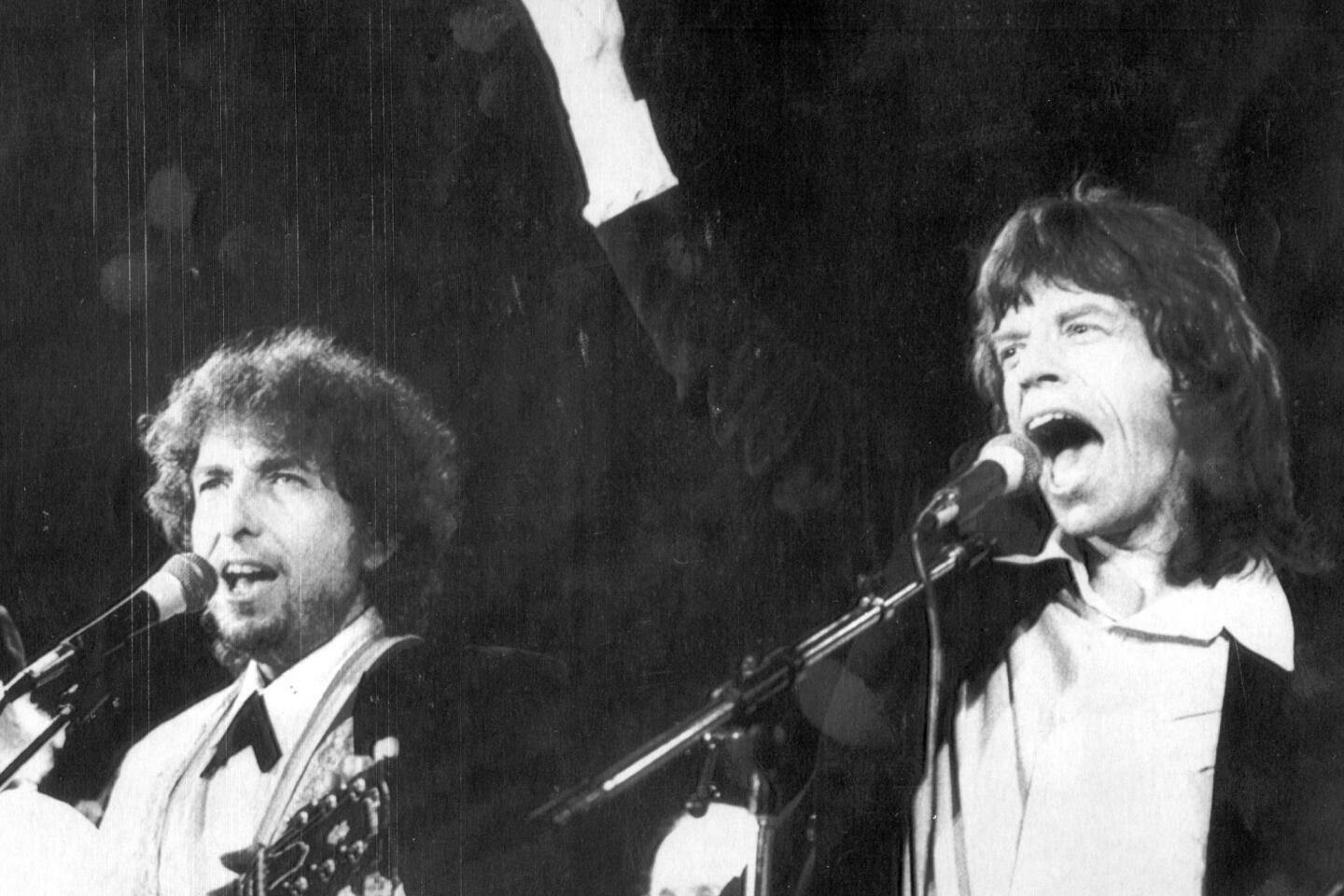

How’s this for legitimate? On Thursday, Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature for “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition,” as the Swedish organization responsible for the award put it. Previous winners include Doris Lessing, Günter Grass and Toni Morrison.

Dylan’s selection triggered immediate reaction online, including some from writers who expressed disapproval.

On Twitter, “Gods Without Men” author Hari Kunzru called it “the lamest Nobel win since they gave it to Obama for not being Bush,” while Irvine Welsh (of “Trainspotting” fame) wrote, “I’m a Dylan fan, but this is an ill conceived nostalgia award wrenched from the rancid prostates of senile, gibbering hippies.”

Yet Kevin Dettmar, chair of the English department at Pomona College, said the Nobel committee got it right — or close to it.

“ ‘Poetic expressions’ suggests local incidents of great lines,” Dettmar said. “I’d say ‘poetic expression.’ What Dylan has done is evolve a new idiom for pop music — intelligent, playful, introspective — that draws on poetry to do the work it does.

“It was brave of them to think that way about it.”

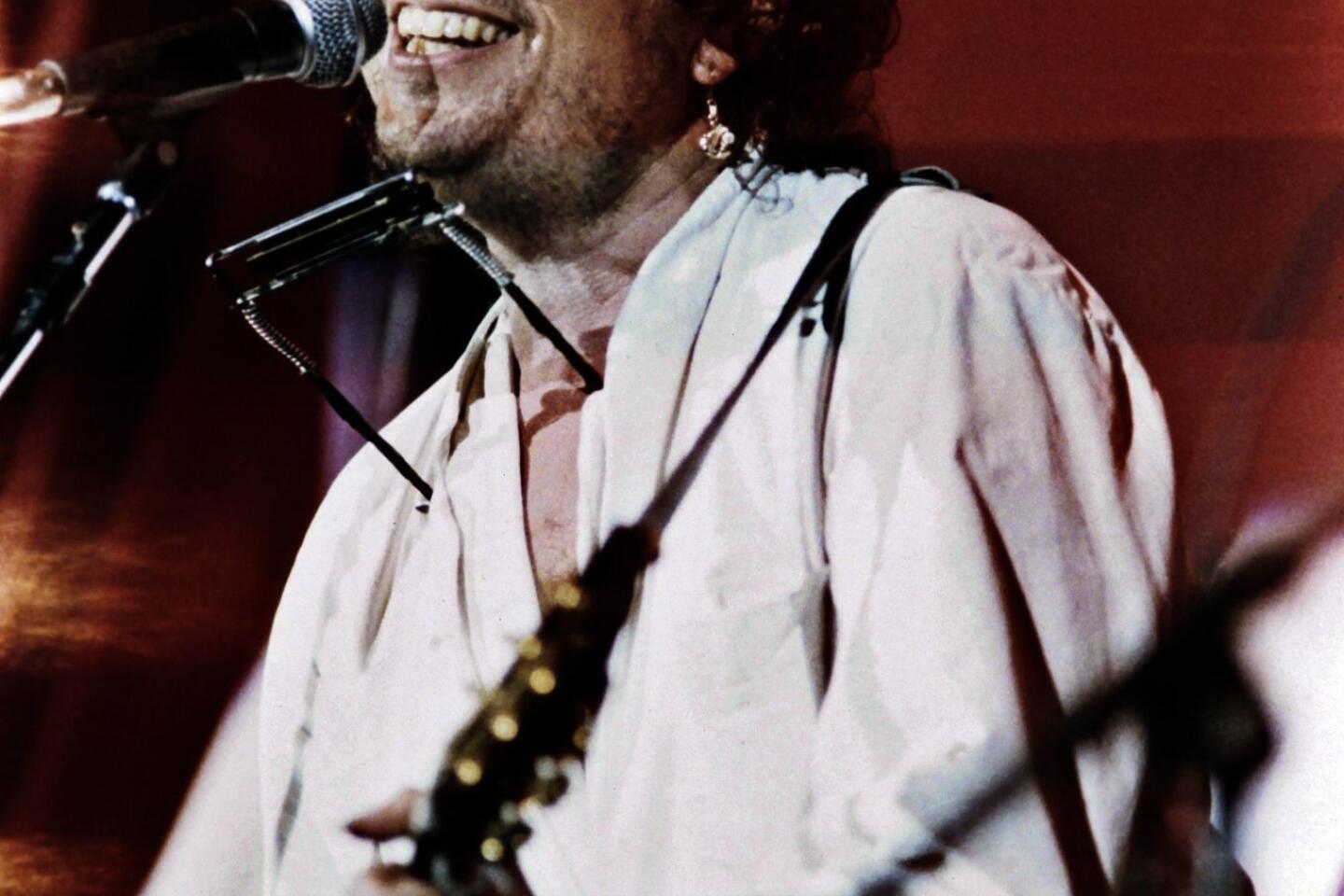

Dettmar, editor of “The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan,” acknowledged that literary types have resisted recognizing the songwriter’s work as poetry because “so much of its effectiveness is in his phrasing.”

“The internal rhyme, the assonance, the consonance — you can see all that on the page,” Dettmar added. “But it’s the way he emphasizes surprising syllables, the way he almost overplays it, that creates this emotional urgency that you really have to hear.”

Still, Wilentz said the publication in 2004 of Dylan’s widely acclaimed book “Chronicles: Volume One” — which he called “one of the great American memoirs” — went some way toward “enhancing his literary bona fides.”

Dettmar agreed, commending Dylan’s “strong allusive voice” that transcended the confessional quality many associate with pop and rock songwriting.

“It’s hard to figure out where Dylan is in the book — or where Robert Zimmerman is,” Dettmar said, using Dylan’s given name. “He’s playing possum all the way through.”

Wilentz also pointed to “Dylan’s Visions of Sin,” a weighty exegesis by British literary scholar Christopher Ricks, as a driver of the star’s growing recognition as an important arranger of words.

As much as he admires Ricks’ book, though, Wilentz insisted that Dylan needn’t be separated from his music to deserve the Nobel.

“Lyric poetry has to be judged as its own form,” he said. “I think it stands up on the page. But why should literature be confined to that?”

Twitter: @mikaelwood

ALSO

Online, some wonder if Bob Dylan really needs a Nobel Prize

Bob Dylan, interpreter: Seven of the artist’s greatest covers

In a ‘radical’ choice, Bob Dylan wins the Nobel Prize in literature

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.