Review: The new John Lewis biography is a stirring tribute that still sells him short

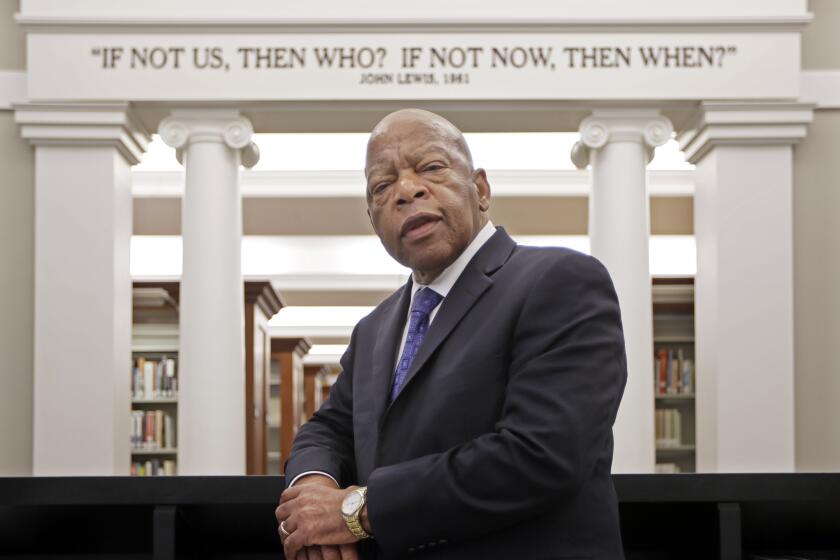

John Lewis, the civil rights activist who would go on to become a long-serving congressman and whose death this summer provoked a national outpouring of grief, woke up in Selma, Ala., on March 7, 1965. He put on his Sunday best, packed a backpack with essentials should he get arrested (two books, a toothbrush, some fruit) and headed out. Just after 2 p.m., Lewis led some 625 marchers on a planned 54-mile march to Montgomery, fighting for the right to vote.

Tear gas, mounted state police and an armed mob met them on the far side of the Edmund Pettus Bridge. As Lewis kneeled to pray, they were attacked. He suffered a concussion and a fractured skull. The attack led ultimately to the introduction of the Voting Rights Act.

That Lewis, barely 25, was at the front should come as no surprise. For even though the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was the most famous advocate of Gandhian nonviolence in the civil rights movement, Lewis was probably its most devoted practitioner, and “Bloody Sunday” was where his legend really took root.

But what Jon Meacham, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author and longtime MSNBC pundit, overlooks in his new account of Lewis’ ‘60s activism, “His Truth Is Marching On,” is the hard work that turned galvanizing protests into durable gains. Readers who know little about Lewis will find an often moving story, but it will prove unsatisfying to anyone seeking a deeper understanding of the movement.

The book is heavily influenced by a series of interviews Meacham did with the congressman near the end of his life. (Lewis also contributes an afterword.) The aim is less a comprehensive biography than “an appreciative account of the major moments.” The broader goal? To show “the theological understanding [Lewis] brought to the struggle, and the utility of that vision as America enters the third decade of the twenty-first century amid division and fear.”

Over the last two decades, Meacham has chronicled the deep divides in American life. His books, most notably “American Gospel: God, the Founding Fathers, and the Making of a Nation” (2007) and “The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels” (2018), have sought to bridge those divides by championing the value of a civic Christianity in politics and an American history that wants to inspire by reinforcing perceived core values.

John Lewis, an icon of the civil rights era and a longtime member of Congress from Georgia, has died.

For Meacham, the pre-1965 Southern civil rights movement — and the career of the young Lewis in particular — connects these themes to today’s racial reckoning. He sees Lewis as “a reminder that progress, however limited, is possible and that religiously inspired witness and action can help bring about such progress.”

Meacham’s impulses are laudable but more suited to an op-ed, in which stirring rhetoric trumps nuance. Stretched to book length, the history gets shaky, reliant on a dated understanding of the movement as primarily regional and religious, rather than national and political, and emphasizing what today are its most noncontroversial aspects: The nonviolent protests against segregated stores and buses.

Not that Christian faith wasn’t important; the best sections of the book highlight the role of religion in Lewis’ life and the Southern civil rights movement. Meacham keys in on the 1958 arrival of Rev. James Lawson in Nashville, where Lewis was attending American Baptist Theological seminary. In Lawson’s workshops on Gandhian civil disobedience, Lewis read Henry David Thoreau, Reinhold Niebuhr and Lao-Tzu. Perhaps most important, he developed a larger vision of the “beloved community,” which he described as “nothing less than the Christian concept of the Kingdom of God on earth.”

Rep. John Lewis of Georgia embraced a message of love and unity, but also discomfort and disruption, without which there can be no true social justice.

The bulk of the book, six of its seven chapters, covers his life before 1965. As Meacham shows, Lewis’ intellectual and spiritual commitment to nonviolence fueled a remarkable reserve of courage during the sit-ins and the freedom rides, where he suffered terrible beatings. In Mississippi’s Parchman prison, he was stripped, poked with cattle prods, blasted with a fire hose and made to stand soaking wet in front of freezing fans. Lewis’ courage earned him the chairmanship of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in 1963 and with it an invitation to speak at the March on Washington.

Here’s the problem with reducing Lewis’ life to his time in the movement: It turns the movement into the John Lewis story. Meacham’s ideas about Christian witness fit the protests against segregated spaces but hold less value in understanding mobilizations against discrimination in jobs, housing and schools. The center of Southern movement activism shifted away from urban sit-ins to rural voter registration and, well before the events in Selma, spoke more about political power than piety. By early 1963, the most important action was in Mississippi, where Bob Moses helped frame voter registration as nonviolent direct action in a way Lewis and the others from Nashville hadn’t anticipated — linking protest directly to electoral politics.

Meacham hurries through the late ’60s, hewing to a shopworn chronology that sees Lewis’ influence displaced by Black Power advocates. Even as Stokely Carmichael, who replaced Lewis as head of SNCC in 1966, advocated Black-only political parties in the South and a move from nonviolence to self-defense, Lewis went in the opposite direction — from passive resistance to active collaboration — believing that Black political success lay within the two-party system. He joined Robert Kennedy’s presidential campaign in 1968. “The America Bobby Kennedy envisioned sounded much like Beloved Community,” Lewis told Meacham.

Even though Lewis lived for an additional 52 years, including 33 as a member of Congress, this story ends there. Freezing him in 1968 contributes to the persistent myth that the noble, inspiring part of the civil rights movement — grounded in Christian faith, with clear moral choices and obvious villains — ended in the ’60s. Meacham’s decision to eschew a full biography seems to have been also motivated by the 2020 election, aimed at drawing a parallel between Trump’s resurgent white nationalism and white segregationists.

Walter Mosley, Luis Rodriguez, the coiner of #BlackLivesMatter and others sketch a hopeful future for L.A. and the U.S. after George Floyd protests.

And yet, in doing so, he misses so much. Lewis’ leadership of the Voter Education Project in the ’70s, which registered 4 million African Americans, shows that the success of the Voting Rights Act owed as much to quotidian work as to the violence on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. It also helps us better understand that, while attacks on the VRA are rooted in the political power Blacks have gained since 1965, Supreme Court rulings gutting it relied on the opposite reading of history — that the movement largely ended when the marchers arrived in Montgomery.

Far from being marginal to more radical Black power critiques, Lewis’ work registering voters, serving in the Jimmy Carter administration and winning seats on the Atlanta city council and in Congress is a microcosm of Black politics in the 1970s and ’80s. As former President Barack Obama noted in one of the less soaring but most essential points of his eulogy, Lewis moved from protest to politics because “We also have to translate our passion and our causes into laws and institutional practices.”

This week’s Democratic National Convention will pay tribute to Lewis’ life just ahead of Joe Biden’s nomination speech. As the clock ticks down to this year’s most consequential election and the threats to fair elections come not from burning crosses but broken mailboxes, it might be that the lesson we need most from John Lewis’ life is drawn not from his faith but, as Obama suggested, from his works.

Eulogies delivered by Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and others at the funeral of John Lewis honored the man — and the power of the spoken word.

Lewis is the author of “The Shadows of Youth: The Remarkable Journey of the Civil Rights Generation,” among other books.

His Truth Is Marching On: John Lewis and the Power of Hope

Jon Meacham

Random House: 368 pages, $30

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.