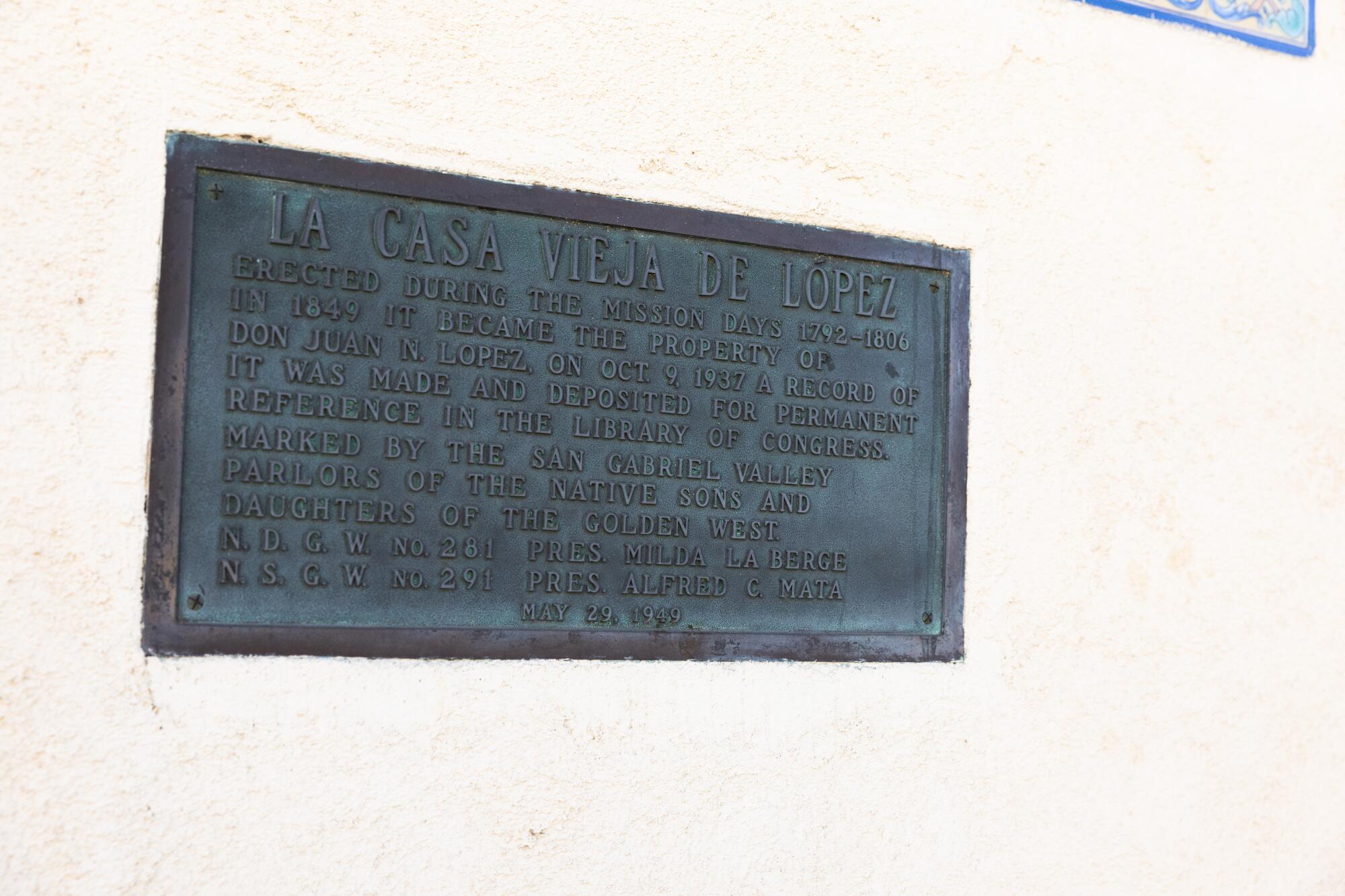

In 1937, the U.S. Department of the Interior certified La Casa Vieja de Lopez Adobe in San Gabriel worthy of preservation for its historic and architectural interest. Eighty-six years later, it’s on a list of structures that architects believe should be recognized — not just because the adobe was built more than two centuries ago — but also because of the incredible woman who lived there.

“We discovered that, not only was the building a rare vestige of the California mission era, it was the home of María [Guadalupe Evangelina] López de Lowther,” said Andrew Goodrich, architectural historian and preservation planner at Architectural Resources Group.

Suffragist, World War I hero, academic and preservationist, López de Lowther was born in the adobe in 1881 as one of 11 children and lived there most of her life. Her father, Juan Nepomuceno López, a silversmith from Sonora, Mexico, bought the adobe in the late 1860s, although it’s believed to have been built between 1790 and 1806 as part of the San Gabriel Mission.

López de Lowther graduated from the Los Angeles State Normal School, which is now UCLA. She is believed to be the first Latina to teach at UCLA and the youngest instructor at the time, said UCLA historian Cynthia L. Chamberlin.

López de Lowther also attended UC Berkeley and Columbia University. She taught Spanish at high schools in Los Angeles and New York, and at UCLA and USC. She was also contracted by the L.A. Board of Education to “teach teachers” the correct pronunciation of Los Angeles.

Where can you go in Los Angeles to uncover these stories? Here are 10 interesting and historic places to learn or think about L.A.’s Mexican history.

But it was López de Lowther’s contribution to the suffrage movement that caught the attention of Goodrich’s team, which was hired by the city of San Gabriel to conduct a historic resources survey to identify potential historic sites within the city.

In the summer of 1911, López de Lowther traveled through Southern California, passing out fliers on women’s rights to vote and giving rousing speeches in Spanish. As president of the College Equal Suffrage League, she tried to sway Spanish-speaking men that women should have the right to vote.

At a suffrage meeting in Montecito, “Miss López seemed to have made a great personal hit with her countrymen for when she left she was cheered until her carriage was out of sight,” an article in Santa Barbara’s the Independent said.

On Oct. 10, 1911, California women won the vote by a slim margin — “an average majority of one vote in each precinct in the state,” according to the National Women’s History Project. Suffrage lost in San Francisco and it was Los Angeles and rural counties that tilted the scale, making California the sixth state to pass it. De López is considered a major contributor to the success of the campaign.

For Chicanos in particular, the sweet treat has become a mascot. But what is it about the concha that has elicited such fanfare?

“I’m not going to say it was all down to her, but I think if the Spanish-speaking population, or if the bilingual population, hadn’t voted in as large numbers in favor, then suffrage for women may not have passed in 1911,” Chamberlin said.

While working in New York high schools in 1917, she took classes in auto mechanics and aviation at Columbia University to prepare herself for volunteer service in World War I as part of the National League for Women’s Service.

“’It’s just a chance,’ she says, ‘whether I’ll ever return, but I am ready and willing to make the sacrifice for my country, I have no one depending upon me, and my country needs me, so I must go,’” López de Lowther wrote in a letter quoted in a Times article from May 26, 1917 titled “Noted Local Teacher to Go to War.” “’The idea of flying and of going to France thrills me.’”

In France, López de Lowther, who spoke fluent French, tended to wounded soldiers in a makeshift hospital at a chateau. One night, in June 1917, the chateau came under fire and López de Lowther pulled wounded soldiers from the building, earning her a commendation from the French government.

Many first-generation Latinos in the U.S. are searching for ways to connect with their roots. For these students, the answer lies in folklórico.

After the war, she went back to New York, where she married another academic, Hugh Lowther, in 1920. They moved to San Gabriel and lived in her family’s adobe while she taught at UCLA until her retirement in 1948.

The adobe has had several updates since López de Lowther’s father bought it, including a kitchen, bathroom and fireplaces — much of it with tile, fixtures and hardware from López de Lowther’s travels to Mexico, Spain and France, according to documents found at the San Gabriel Historical Assn.

She sold the adobe to the mission, which is part of the Los Angeles Archdiocese, when she moved to Laguna Hills in 1965. She lived into her mid-90s and died in 1977.

The adobe became a museum for a while, was sold to the city and then sold back to the archdiocese. It’s currently closed to the public.

A staggering 81% of Latinos in the U.S. consider addressing climate change to be a priority compared to 61% of non-Latinos, according to Pew Research.

“It needs a lot of work,” said Terri Huerta, director of development and communication for the mission. There had been talk of making the adobe into a retreat center years ago, but recovering from the 2020 arson fire at the mission put plans on hold.

The adobe — also known as the López de Lowther Adobe — is on a list of buildings compiled for the city’s historic resource survey that could qualify for city, state and national historic recognition.

It turns out, though, that the adobe is already on the National Register of Historic Places, Huerta said. When the San Gabriel Mission was added to the National Register in 1971, it didn’t specifically include the adobe as part of the 8-acre complex. In 1980, the Adobe was officially added, but it’s not widely known.

What does that mean for the adobe? Not much. Listing a house on the National Register doesn’t mean it will open to the public, or that resources will automatically become available to restore it, but it does allow property owners to apply for government grants for rehabilitation.

In his career of more than five decades, Boulton chronicled the evolution of his nation and was a key figure in shaping the art scene in his country.

López de Lowther isn’t around to advocate for her home as she did in the 1950s. It was her activism that saved the adobe when the widening of Santa Anita Street was going to take La Casa Vieja, according to an article in Pasadena’s Independent Star-News.

“It’s amazing it’s still standing after all this time,” Goodrich said. “Los Angeles has a history of demolishing its history. That there is something this old and this significant that is still there is incredible.”

Yvonne Condes is a freelance writer and contributing editor to Picturing Mexican America, a project that works to uncover the whitewashed history of Mexican Los Angeles. You can find her on Instagram: @yvonneinla.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.