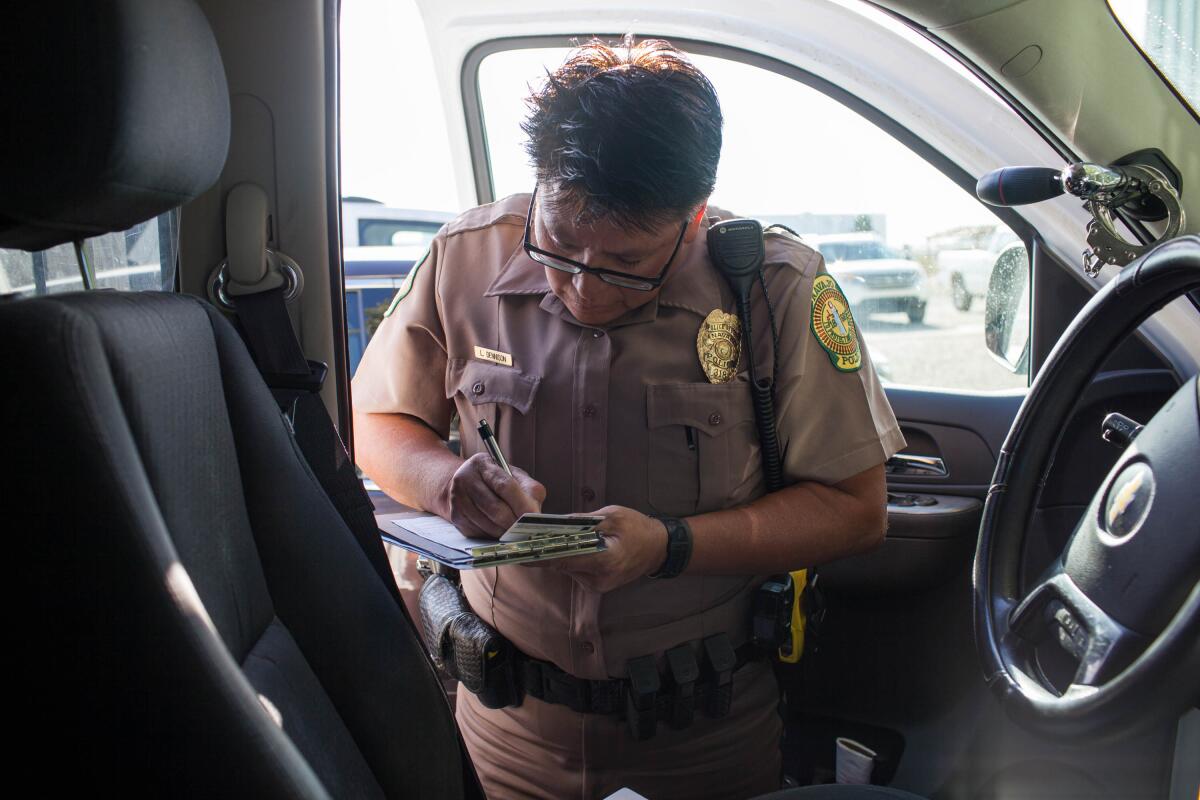

On a vast reservation, female Navajo officers patrol with bulletproof vests and protective amulets

SHIPROCK, N.M. — Officer Lojann Dennison was just ending her shift when she took the 10 p.m. assault call. She was tired as she headed out into the profound darkness of the reservation.

Her Chevy Tahoe police cruiser bumped along dirt roads with ruts deep enough to loosen a tooth filling. Territorial dogs barked and gave chase. After 40 jarring miles, Dennison arrived at a clutch of mobile homes where family members confronted a young man who had just beaten his intoxicated uncle to death.

She switched off the ignition and stepped out into the moonless night, alone. Dennison, a 20-year veteran with the Navajo Nation Police Department, was troubled by an all-too-familiar thought: Timely backup on the sprawling Indian nation was a luxury her understaffed department could not afford.

She patrols one of seven districts on a Navajo reservation that is home to 180,000 people. Among 500 sovereign tribal nations in the U.S., the Navajo are among the few with their own police force. The vast majority of the department is Native American.

That means Navajo patrolling Navajo, with aspects of the job far outside typical rural policing: She struggles with deeply rooted customs that can call for an officer to choose between allegiance to clan ties and upholding the law. She wears a bulletproof vest but also wears a protective amulet and conducts ritualistic cedar burnings in the way of her ancestors.

On this summer night, the situation appeared to be headed toward chaos. Dennison had handcuffed the nephew and put him in the back seat of her vehicle, where he explained the killing: He’d grown tired of being picked on whenever his uncle got drunk.

Meanwhile, two women ordered Dennison to remove the body because Navajo culture instructs a sacred mix of fear and respect for the dead. She told the women the body had to stay in place until the coroner arrived.

Then one woman pushed her, calling for street justice. She banged on the windows of the locked cruiser, urging for help to pull the terrified nephew from the car.

Dennison radioed for backup, performing a mental inventory on her weaponry: the Glock 22 .40-caliber handgun at her side and the AR-15 assault rifle locked down in her cruiser.

“It’s a scary feeling. We have all these tools on our belts, but I’ve never been involved in an officer-involved shooting,” she would recall later. “But that night, alone, facing off against those women, I told myself, ‘I’m going to have to use my weapon here.’”

She didn’t. At 5-foot-4 and with short moussed hair, the 47-year-old Dennison is hardly an imposing figure, but through force of personality and smarts earned in decades on the force, she kept the situation from spinning out of control. Her backup didn’t arrive for an hour.

::

At 27,000 square miles, the Navajo reservation spreads into Arizona, Utah and New Mexico — an area about the size of West Virginia. Tasked with patrolling 1,000 square miles of territory, officers can travel two hours to reach a crime scene. Some 40% of the reservation is a cellphone dead zone, and 60% lacks the two-way radio coverage officers use to keep in contact with their home base.

Since 2011, three Navajo officers have been killed and several injured — all overwhelmed in isolated areas, all alone. The last, Officer Houston James Largo, was killed in 2017 while responding to a domestic violence call; he’d called for backup but was outside two-way radio contact.

While the FBI pursues major crimes, such as murder and rape, Navajo officers act as first responders who conduct field interviews and protect evidence. The department counts just 200 officers, a skeleton staffing rate well below the national average and half of what commanders say is needed to adequately patrol the reservation.

Female officers such as Dennison are a key part of the department’s approach to one of the toughest policing jobs in America. Navajo Police Chief Phillip Francisco has actively encouraged the hiring of female officers. They now comprise 20% of the force, compared with other U.S. police departments, which on average are 13% female, according to the National Center for Women and Policing.

Female officers can be more effective than men in handling abuse against women, which is pervasive here, experts say. Recent federal figures show that more than half of Native American women in the U.S. have suffered sexual or domestic violence in their lives.

For Dennison, domestic violence had touched her own family. And when she had to, she didn’t hesitate to arrest her own brother.

He was much older and had helped raise her. He also was a former Navajo cop, one of the reasons she’d joined the force in 1997. (The other lure was that $25-an-hour jobs were rare on the reservation.)

Column One

Column One is a showcase for compelling storytelling from Los Angeles Times.

In 2005, Dennison arrived at her brother’s house in Tuba City, a place she’d visited many times for family functions. This time, her sister-in-law stood outside, shaken and crying after a confrontation with her husband.

Dennison told the wife, “You don’t deserve this.”

When Dennison clicked on the handcuffs, her brother turned to her: How could she do this? He’d just been upset with his wife. How could she take her side?

Dennison said her badge meant something beyond clan ties. He was an abuser, and he was going to jail. The other officer offered to transport the brother.

Dennison waved him off. “No. I’m gonna take him. I’m gonna book him.”

Dennison’s brother didn’t speak to her for a year. But she made sure that the rest of her family understood her decision. “I explained that I was just doing my job, that it was my duty. They understood.”

::

Although female officers have made strides within the department, Dennison says true equality still eludes them. Many tribal elders say women have no place in police work.

“They sent you?” they’ll say. “Why not a male officer?”

“Yep, they sent me,” she’ll respond. “I can do anything he can do.”

The first female Navajo police officer was hired in the 1960s, elders recall. America was undergoing a cultural revolution in which women demanded greater rights, and Navajo women had traditionally played decision-making roles in tribal affairs.

Back then, tribal policing was in its infancy. Bribery was common and officers avoided contact with outside police agencies. Female officers were required to wear skirts.

Eventually, more women joined the force in the 1980s, and uniforms became standardized. By the 1990s, half of the 50 officers stationed to the Shiprock District — where Dennison works — were female.

In 1992, Officer Dorothy Fulton became the first woman to be promoted to the department’s command staff, and a decade later presided as chief over both criminal investigations and uniformed patrol.

“Women have traditionally taken initiative on the reservation,” said Fulton, who now works as a corrections program specialist for the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs. “Before any major decision was made, the men would turn to the mother and grandmother for their input. Not only that, women have always been hard workers. Navajo culture has always known that.”

The advice Fulton gave new female reservation recruits mirrored her own mother’s counsel when she became a police officer. “As women, we took the same oath as the men, wore the same uniform, drove the same vehicles, carried the same guns, enforced the same laws and fight the same criminals,” she said.

Traditionally, Navajo elders have encouraged women to avoid weapons, and many female officers once performed elaborate ceremonies to bless their department-issued firearms — a way to make them acceptable in tribal life.

Dennison says she doesn’t need permission from anyone to carry her gun. “I’m a tribal police officer. I have a weapon,” she said. “And I’ll use it when I have to.”

::

Dennison had just joined the department in 1997 when she encountered an old woman who was intoxicated and combative. She was a passenger in a car Dennison stopped and began throwing her shoes and purse at the officer.

She also threw something else from a small box: dust and ground-up bones.

Dennison soon began suffering from nausea and migraine headaches that forced her to take time off from work. After a trip to the hospital brought no relief, her father took her to a medicine man.

Dennison had been cursed, he said, touched by a world of ghosts and skin walkers. Until then, she’d never believed in such a thing. Growing up, her grandparents had whispered about the realm of evil spirits, but her mother, a devout Jehovah’s Witness, discouraged her daughter from ever talking about them.

The medicine man gave Dennison an arrowhead talisman and a bottle of mountain herbs to shield her from evil spirits and the perils of contact with the deceased, a regular occurrence in her line of work.

Eventually, the pain subsided. But the episode provided Dennison with new insights into her culture’s ancient beliefs and the risks of tribal policing. Spiritual teachings warn to simply stay clear of the dead, but Dennison often has no choice.

Now, whenever she handles a body as part of her work, she later conducts a ritualistic burning of charcoal and cedar to help ward off any unwelcome spirits.

She calls a brother to do the preparations in the garage and then rushes home to purge herself of evil spirits.

“You smoke yourself,” she said. “You put your uniform in it. Whenever I handle fatal traffic accidents or visit the home of an elder who has died, I do a burning. I always sleep better. Because the afterlife can affect you.”

Among Navajo, the so-called dark side is a phenomenon that is rarely discussed, especially to outsiders. Dennison figures that as many of her fellow officers observe the spirit world as those who don’t, but she rarely, if ever, asks.

With the spread of Christianity and other religions, only one-third of reservation residents remain believers in the dark side, Chief Francisco estimates. Still, because of the danger of their work, police officers of all ranks wear amulets, in the shapes of sacred animals, and are blessed by a medicine man.

Some officers resist long handshakes through which dark forces can be transmitted. Pregnant officers request office duty to avoid encountering dead bodies. In Navajo courtrooms, testifying witnesses can request the suspect’s family be removed for fear they might cast a curse.

Since her brush with the old woman, Dennison has taken greater care in approaching strangers on the job. “I use more caution with people,” she says. “Even though I have my arrowhead and other protections, it’s always there in my head, that it could happen again.”

Some nights, she responds to calls from an elderly store owner in an isolated settlement known as Little Water. The woman reports seeing skin walkers lurking outside her business. And Dennison always goes to check.

So far, she’s never spotted any ghosts. But one night, she passed a figure on the road wearing a large mask that covered most of its upper body. She quickly turned around and went back to investigate.

By the time she got there, the vision had vanished.

But Dennison knows what she saw: “I know it exists, the evil. I know it’s out there.”

Glionna is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.