Proposed L.A. County budget adds mental health workers, homelessness funding

Los Angeles County’s proposed budget for next year is about $1.4 billion smaller than the previous year’s but adds more mental health workers and increases funding to address homelessness.

County Chief Executive Fesia Davenport said at Tuesday’s Board of Supervisors meeting that her budget of $45.4 billion ensures that the county can provide crucial safety net services while remaining financially solvent.

The budget recommends spending $728.2 million in Measure H funding to hire more homeless outreach workers, buy motels and hotels and lease entire buildings to quickly house residents coming off the streets.

Supervisor Janice Hahn said it is the most money the county has ever dedicated to “turning this crisis around.”

Justice advocates Tuesday pushed back on the county’s funding priorities, arguing that too much is going to the Sheriff’s Department, which has a recommended budget of almost $4 billion.

These advocates and county leaders have been at odds the last four years over how much money the county must spend on Measure J, a 2020 criminal justice reform measure mandating that money be set aside for social services.

“While you all have each proudly shared that the budget represents the values of the board, I want to remind you all that you represent the people, and the people have shown up time and time again to demand” that money be divested from law enforcement and allocated for community programs, said Megan Castillo, policy and advocacy manager at social justice nonprofit La Defensa.

L.A. County will potentially have to pay more than $3 billion to resolve about 3,000 claims of sexual abuse that allegedly took place in its foster homes, children shelters and probation camps and halls dating to the 1970s. A state law passed in 2019 extended the statute of limitations, opening the door for such claims.

There is no money in the proposed budget to pay these claims, as the county is still assessing when and how it will address the matter, Davenport said.

The budget could increase if there is money left over from the current fiscal year, or if additional money materializes from other sources later in the year.

Last year, officials presented a $43-billion budget that eventually increased to $46.7 billion. The previous year, the proposed budget was $38.5 billion and increased to $44.6 billion.

This trajectory isn’t guaranteed, however, in the event of a dramatic financial downturn, county officials said.

Over the next two months, the county will hold public hearings on the budget, during which the supervisors can propose changes before voting on it in June.

Doctors and dentists at L.A. County-run facilities are putting off a strike indefinitely, their union says. The walkout had been planned for next week.

If the proposed budget is approved, L.A. County will add 835 jobs for a total of 116,159 positions.

The county has negotiated new contracts with the majority of its labor unions, and represented employees will see cost-of-living raises, Davenport said. No layoffs are expected.

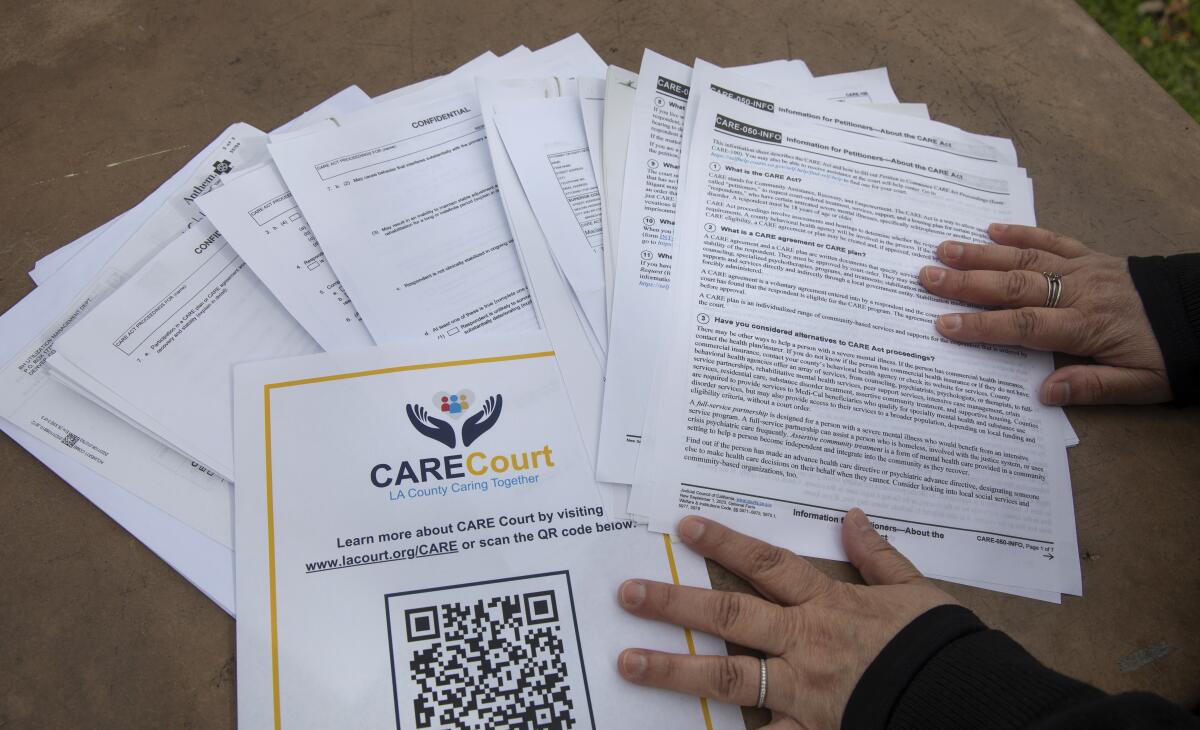

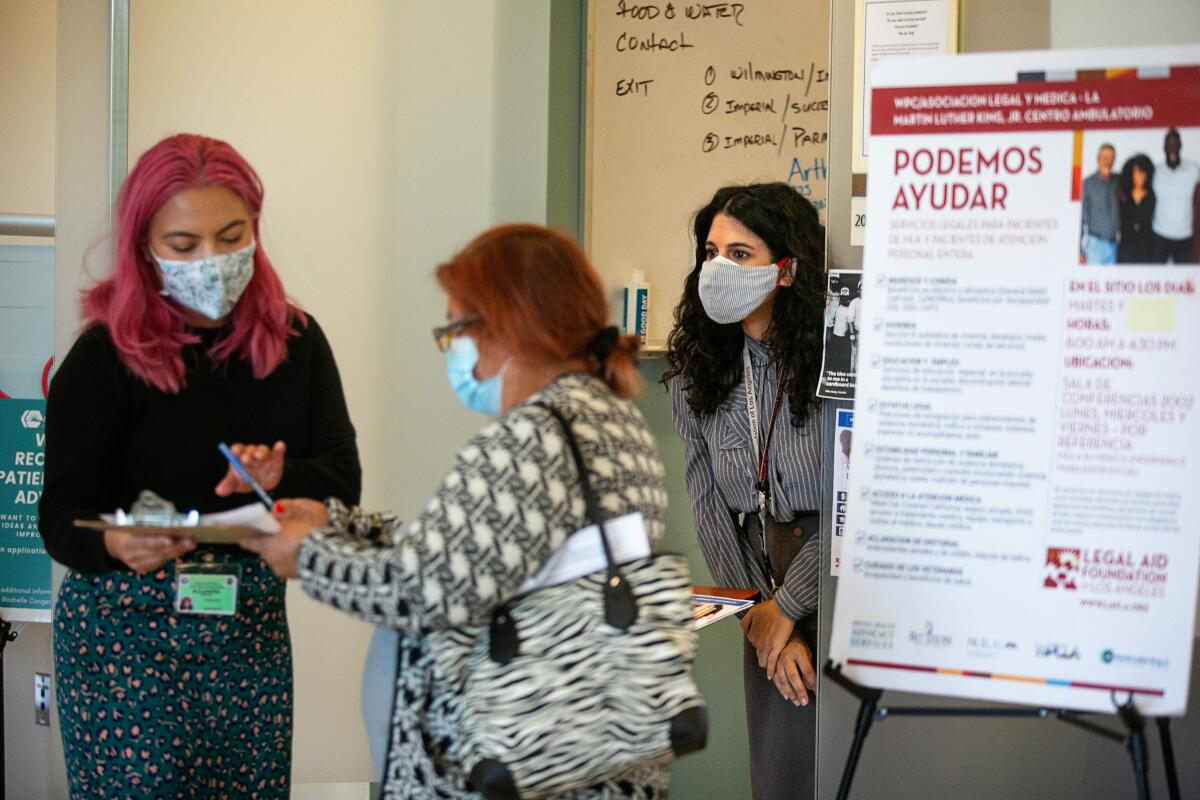

More than half of the new jobs — 452 positions — will be at the county Department of Mental Health to run the new CARE Court program, which allows families and others to petition for care for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and to expand staffing on homeless outreach teams and in county clinics.

The agency has seen increased interest from job applicants after struggling in recent years to attract such candidates to clinics known for high case loads of acutely ill patients. The department offered money to pay for student loans and other incentives that helped recruit more people, leaders said.

“I’m happy to see that we have 452 staff that are going to be brought into the mental health department, but we know that we could probably use 1,500,” Supervisor Hilda L. Solis said. “That’s probably what we realistically need.”

Davenport said the budget represents a set of choices, “sometimes very difficult ones,” made in recent months after receiving thousands of individual requests and meeting with the county’s 38 departments.

County leaders requested $2 billion over what Davenport’s office could find money to finance, she said. Her proposed budget recommends that the county finance $833 million of the requests in future budget years, leaving the rest unfunded.

Property taxes make up about 20% of the county’s budget and can be used for essentially any purpose the supervisors see fit. But much of the rest of the budget is restricted by state and federal law to be spent on specific programs, Davenport said.

“We cannot use, for example, Medicare dollars to fill potholes in our unincorporated areas, and we cannot redirect state funding for Project Homekey to support county commissions, no matter how great the need,” Davenport said.

As is typical in the county budget hearings, the decision of what to not fund brought several questions from the supervisors.

Hahn said she was disappointed that the chief executive’s office had declined to fund a request from the public defender’s office for 10 additional public defenders and 20 psychiatric social workers.

At Hollywood’s mental health courthouse, public defenders have said they’re assigned at least 500 cases each and have allegedly been told by their boss to stop declaring doubts about the ability of their mentally ill clients to stand trial, according to a grievance the union filed last year.

Hahn said that without more support, public defenders can’t identify clients with serious mental illnesses for diversion programs.

“What’s important about this request is it is clearly a net within the safety net in our county,” Hahn said.

Supervisor Lindsey P. Horvath said she wanted to see $3 million added to the county’s budget to finance legal help centers, which have educated thousands of tenants facing eviction.

“That’s $3 million well spent for all the people we’re able to protect from falling into homelessness,” Horvath said.

But these requests were unfunded, in part, as the county’s economic outlook is “challenging,” Davenport said in a news briefing Monday.

County officials anticipate less property tax revenue as interest rates climb and real estate transactions slow, Davenport said.

L.A.’s financial district, once the thriving heart of downtown, struggles to bounce back from pandemic shutdown and homeless crisis. Experts say it needs more housing, fewer offices.

Four years into the COVID-19 pandemic, some of L.A.’s commercial real estate remains empty as employees continue working from home. That could also translate into less tax money coming into county coffers, Davenport said.

California faces a budget deficit of at least $38 billion, and L.A. County could lose $127 million as a result of the state shortfall.

Another financial unknown relates to how much L.A. County will pay to address substandard conditions in its jails. In the coming year, a judge could mandate that the county spend more money on mental health care and other services in the jails.

The county also must spend hundreds of millions to seismically retrofit about 33 concrete buildings, including the Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration, which is the headquarters for the supervisors and houses offices for multiple county departments.

The Measure H quarter-cent sales tax approved in 2017, a major funding source for homeless services, will expire in 2027. If it isn’t extended or replaced, the county will lose millions.

Times staff writers Rebecca Ellis and James Queally contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.