As the pandemic shut down office life in Los Angeles’ downtown financial district, Claude Cognian tried to keep his gastropub Public School 213 open. But the evacuation of white-collar workers made way for an influx of homeless people and drug users — and more than a few troublemakers striding in the front door.

“It was hard to keep hostesses at the door, because they got scared,” said Cognian, chief executive of the restaurant’s parent company, Grill Concepts Inc.

Three break-ins cost as much as $12,000 each time just to repair the windows, all while the bottom line was cratering in the absence of the office employees who used to gather for lunch and after-work drinks. With sales down 75% from pre-pandemic days, his company closed the downtown gastropub in August and is not planning to return.

“Our bet was that downtown was going to come back, and it hasn’t,” Cognian said.

For decades the Los Angeles financial district was the beating heart of downtown, the corporate muscle that gave the city of sprawl a soaring glass skyline. But the pandemic and the wave of remote work hollowed out its skyscrapers and helped shut many restaurants and businesses that relied on crowds of workers. Though the neighborhood shows signs of recovery, few expect it to return to being the bustling hive of suits and ties that it was.

To many insiders — the urban planners, real estate developers and business owners with interests in it — the area will recover only if its identity grows more textured than a zone of white-collar office space.

Desirable office addresses were already spreading beyond the financial district before the pandemic, as downtown experienced a renaissance in housing, art and entertainment on blocks previously shunned by investors and residents.

To the south, billions of dollars were spent improving the blocks around Crypto.com Arena with hotels, housing and entertainment venues. Obsolete century-old commercial and industrial buildings to the east were renovated into desirable housing and fashionably unconventional offices. Billions more were spent north on Bunker Hill where the Music Center including Walt Disney Concert Hall and office skyscrapers have been joined by museums, apartments and a high-rise hotel.

Architect Frank Gehry’s latest project opens in downtown Los Angeles.

The housing boom drew residents to the financial district as well, and that has kept it from turning into a ghost town.

But for the area to truly come back to life, many say it will need to follow the path of Lower Manhattan. The financial capital of New York faced an exodus after 9/11, but city officials and investors staved it off by making it a place of more diverse uses. It is still an office district but is far more lively than it used to be since it also became a residential neighborhood with more shops, restaurants, parks and hotels than it had before the attacks. A performing arts center will open in September.

“Cities evolve. That’s what they do,” said downtown L.A. business representative Nick Griffin. “From natural disasters, wars and pandemics. They evolve with market changes, customer preferences and cultural shifts. Downtown has evolved pretty dramatically over the last 20 years and the next five or so are going to be very interesting.”

Many companies have returned to their offices, but on a limited basis as their employees work some days from home. “For Lease” signs clutter building fronts, tacked over restaurants and bars that once served lively hordes of office workers. Graffiti marks windows.

At Public School 213, the chairs are stacked neatly on tables as if it just closed for the night. Other former restaurants have been gutted by their landlords. Sidewalks are quiet, sometimes eerily so.

Downtown’s centers of gravity have shifted numerous times since its days as a remote Spanish pueblo.

The plaza by Olvera Street near the Los Angeles River was el centro until the late 19th century. When the railroads arrived in the American era, the business elite shifted the commercial district south from the plaza toward 1st Street in the Anglo section of the racially divided city, said Greg Fischer, an expert on the history of downtown who worked on planning matters for former City Councilwoman Jan Perry. Main, Spring, Broadway and Hill streets became the business hub.

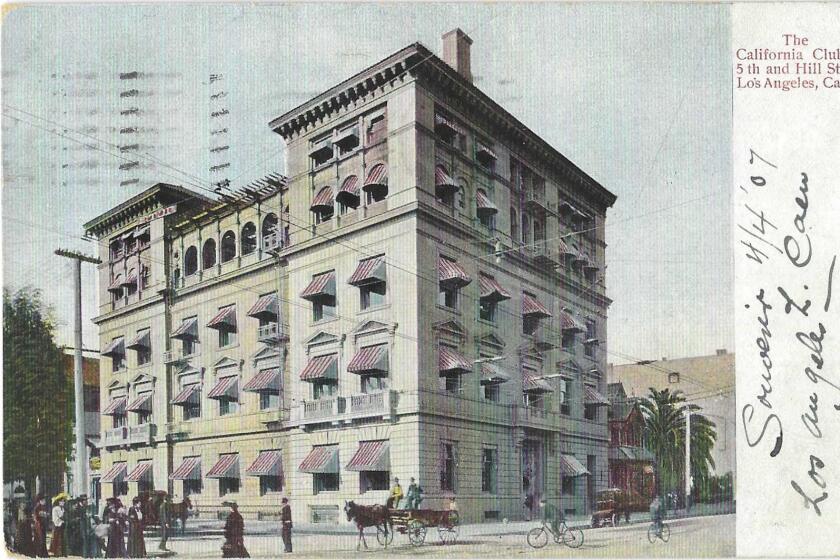

In the early 20th century, elite social clubs such as the Jonathan Club, the California Club and the Los Angeles Athletic Club erected new buildings on the west side of downtown where property was relatively cheap. Soon the rooming houses, small apartment buildings and ramshackle Victorian homes there gave way. Richfield and other oil companies headquartered there, the seeds of today’s financial district.

An L.A. Times exposé — and in one instance, Gloria Allred quite literally exposing sex discrimination — led the Jonathan Club, the California Club, the Friars Club and others to become less exclusive, if not less expensive.

In “the Jetsons era,” as Fischer described the 1960s, corporate leaders viewed the Spring Street-centered office district as increasingly obsolete and passé and moved to newer buildings in the financial district. Downtown lost a lot of its lifeblood during that time, he said.

“In the years after World War II, downtown was a shopping, office and entertainment area,” Fischer said. “By the 1960s the office component had shifted west, most entertainment went to suburbs and housing just evaporated.”

Among the big businesses with offices in the west were the Richfield, Union, Signal, National and Superior oil companies. Pacific Mutual Life Insurance Co. was headquartered there and Bank of America had a big presence.

The boundaries of the financial district are not officially outlined, but property brokerage CBRE defines it as the office center south of Bunker Hill and 4th Street, flanked on the west by the 110 Freeway and on the east by Hill Street and extending south to 8th Street.

By the 1980s, much of downtown was moribund; buildings that once thrummed with commerce were dilapidated and vacant or underused. There were pockets of vibrancy, notably the Jewelry District and a Latino-centric shopping zone that emerged among aging buildings along Broadway in the Historic Core. The Civic Center around City Hall remained one of the largest concentrations of public administrative buildings in the country, employing thousands of workers.

But the financial district was the shiny thriving part of the city, a high-rise office park for lawyers, bankers and accountants who piled into their cars for a mass exodus at the end of each workday.

To many, the neighborhood felt like a corporate fortress, invisibly walled off from the rest of downtown. Business leaders were painfully aware that downtown L.A. lacked the vibrancy of other big cities because it had so few residents, but was stuck in a chicken-and-egg dilemma: People didn’t want to live there because it lacked restaurants, grocery stores and other typical city-life amenities, but merchants didn’t want to set up shop because few lived there.

The stalemate began to break around 2000 with an ordinance that made it easier to redevelop obsolete office buildings into housing. The relocation of the Lakers, Clippers and Kings pro sports teams to the new downtown arena then known as Staples Center brought thousands of sports and music fans and led a wave of development south of the financial district.

Decades of efforts to add rail service and thousands of apartments and condominiums helped create a more vibrant downtown that was taking on the flavor of other big cities before the pandemic.

“All of a sudden people were walking dogs and pushing baby carriages,” architect Martha Welborne said. “New restaurants came in, even destination restaurants that weren’t just for the people who worked downtown or lived there.”

Fortunately for downtown’s future prospects, its apartment towers remain nearly fully occupied. More than 35,000 units were built after 1999, when so few people lived there that downtown didn’t even have a big-chain grocery store.

Three new hotels have recently opened and a 42-story apartment tower will start leasing later this year. Bottega Louie, one of the region’s top-grossing restaurants before it shut down during the pandemic, reopened in 2021. A few blocks away, legendary Beverly Hills steakhouse Mastro’s also opened a seafood restaurant last year near Crypto.com Arena.

And last week, Metro opened its new Regional Connector, a 1.9-mile underground downtown track adding three stations and linking different lines to make travel more seamless.

Though some business owners have abandoned the financial district, others see an opportunity to get in at an affordable price during what they hope is a temporary economic dip.

Restaurateur Prince Riley recently leased a spot on Grand Avenue that was last home to the Red Herring restaurant. He grabbed it because he liked the location and it was already built-out for upscale dining.

“You can see all the love and care that went into this space,” he said. “They were a casualty of COVID.”

Riley and his wife plan to open their restaurant, named Joyce, in July, featuring a raw bar and Southern-style seafood such as crudo and ceviche. They moved into the apartment building upstairs to be close to it.

The couple like being near Bottega Louie, a popular Whole Foods grocery store and the recently opened Hotel Per La, which took over a lavishly refurbished 1920s building last occupied by another hotel that closed early in the pandemic.

“I can see business picking up,” Riley said. “This is an opportunity from a terrible tragedy like COVID. We wouldn’t have had this otherwise.”

A key factor keeping downtown teetering between recovery and a further downward slide appears to be discomfort with the streets and the sense that they are not as safe as they were before the pandemic.

The blocks close to Metro’s underground 7th Street/Metro Center station, where multiple light and heavy rail train lines meet, are among those that have changed the most since the pandemic as the Metro system struggles to combat rampant drug use and serious crimes such as robbery, rape and aggravated assault on its lines.

The growing number of homeless people on the streets has been an issue in other cities too, said Cognian of Public School 213. His company also closed restaurants in Seattle and San Francisco because customers at their urban locations trickled away as unhoused people commandeered the sidewalks.

“Hopefully, we as a city, as a state, find a solution for the homeless,” he said. “If the homeless situation doesn’t get solved in some fashion that allows tourists, office workers and businesses to operate, it’s just going to bring down the area.”

Real estate broker Derrick Moore of CBRE, who specializes in matching restaurant and shop operators with landlords, said leasing of retail space downtown has improved in recent months, especially compared to the dark days of the 2020 pandemic shutdown when downtown fell silent.

“It seems like ancient history,” Moore said, “but it was very devastating to one’s psyche.” And to downtown businesses.

In the wake of the COVID shutdown, downtown overall lost more than 100 food and beverage establishments with a combined footprint of more than 1 million square feet, Moore said.

“That’s restaurants, bars and lounges, juice bars, boutique coffee operators and even national brands,” Moore said. “A good portion of those remain vacant.”

Replacement tenants like Joyce restaurant are starting to come in, he said, with leasing and property showings picking up in the first quarter at a “resoundingly” busier pace than early 2022. Moore has taken potential tenants to the empty Public School space, where across the street the failed Standard Hotel just reopened under new management as the Delphi.

Faced with a challenging market, retail landlords have cut their asking rents as much as 50% from pre-COVID prices, Moore said, and more than doubled the amount they are willing to spend on tenant upgrades such as installing restaurant kitchens and restrooms, and providing periods of free rent.

The financial district also faces a struggle of changing tastes, with many firms bypassing the gleaming skyscrapers that were the height of prestige in the late 20th century in favor of campus-style offices and a more laid-back vibe.

Even legal firms, long a stalwart in the financial district, are turning elsewhere in some cases. One firm established in February recently opted out of putting its office there.

“When we started to look at space it became very clear to us that locating in the financial district was a very different proposition than it used to be,” said Matt Umhofer, a partner at Umhofer, Mitchell & King. “Downtown has changed dramatically, and we wanted to rethink what it means to be a law firm in Los Angeles and let go of preconceived notions of needing to be in the financial district in order to be relevant.”

The fledgling firm opted instead for an office in Row DTLA, a campus of shops, restaurants and offices created out of century-old warehouses near the Arts District, east of the financial center, even though office rents in the Arts District are often higher than they are in the glitzy skyscrapers.

“The short version is, being in the financial district isn’t as cool as maybe it was in the past,” Umhofer said.

The spotty attendance of office workers has changed the character of business centers across the country, said Mark Grinis, leader of consulting firm EY‘s real estate, hospitality and construction practice.

An analysis by EY found that offices are being used at only 25% to 50% of the level they were before the pandemic.

“In some locations, three-quarters of the people that normally would have gone in, didn’t,” Grinis said. “People are not on the subway, ordering sandwiches at lunch or having a drink after work.”

Vacant offices and storefronts can hinder recovery, he said, because people shy away from empty spaces.

“Three blocks of vacant houses in a residential neighborhood ultimately becomes a negative,” he said. “An office center is not that different.”

The physical appearance of vacancy becomes more alarming when graffiti, litter and grime follow and create a bad “multiplier effect,” Grinis said.

Stopping the spiral starts with making the streets safe and getting homeless residents into better housing, but there are also public policy decisions that could help landlords convert office buildings to housing if they are no longer competitive on the office leasing market.

A growing number of Los Angeles-area office buildings are being converted to residential use as demand for offices stalls.

And the market has been brutal. Owners of some of downtown’s office high-rises have faced defaults, foreclosures and rushed sales in the face of falling demand, real estate data provider CoStar said.

The owner of two of the financial district’s premier office towers, 777 Tower and Gas Company Tower, said in February that it defaulted on loans tied to the buildings. Other high-rise owners are in similar straits.

In the face of rising vacancy rates, “those defaults could signal pain to come for the 69-million-square-foot downtown L.A. office market,” CoStar said.

Owners of buildings facing foreclosure sometimes don’t have enough money to build out new tenants’ offices, as is customary, which hinders strapped landlords from recovering financially.

Commercial landlords are getting hit on multiple fronts, said Jessica Lall, managing director of the downtown office of CBRE.

“What we’re seeing is a perfect storm when it comes to the office distress in downtown L.A.,” she said.

Loans on large-scale properties are maturing at a time when interest rates are high, making refinancing a challenge, Lall said. There is widespread uncertainty among tenants about how much space they will need to rent in the future if employees work remotely at least some of the time.

Those issues are compounded by “the general perception around downtown being unsafe,” she said. “All urban centers are grappling with that issue right now.”

The downtown office vacancy rate — the share of total space that is unleased — climbed to 24% in the first quarter, up from 21.1% a year ago, according to CBRE. More empty space is coming, the brokerage said, pushing estimated availability to a daunting 30% as some companies shrink their offices or move away from downtown.

Law firm Skadden, for example, a large longtime tenant in downtown’s Bunker Hill district, has decided to move its offices to Century City .

The landlord of the U.S. Bank Tower, downtown’s tallest office tower at 72 stories, remains bullish on the market in spite of its troubles and recently spent $60 million to make the building more attractive to tenants by adding hotel-like amenities.

“People need offices,” said Marty Burger, chief executive of Silverstein Properties, which owns the tower. “Not every company in every industry needs an office, but the majority of them do.”

Among the reasons for offices are collaboration and education, he said. “How do you mentor the young folks who are coming up in your industry if the older people aren’t in the office for younger people to learn from? There is a whole ecosystem where you need people in an office now.”

Companies may end up using their offices fewer days of the week than they used to as remote work and shortened schedules grow in popularity, he acknowledged: “Fridays may never be Fridays again.”

Burger says his optimism about downtown L.A.’s potential for improvement has a foundation in New York, where Silverstein built One World Trade Center on the site of the Twin Towers.

“After 9/11, everyone said that no one would ever live there or work there again,” Burger said.

In 2001, the neighborhood had about 20,000 residents and saw little activity after office hours. Now rebuilt, the neighborhood has about 75,000 residents and a greater mix of office tenants including businesses in tech and advertising in what was mostly a banking center before, Burger said.

“It’s a vibrant 24/7 community,” he said.

Many see this as the best future for L.A.’s financial district.

The city’s tight housing market combined with the downturn in office rentals opens the possibility to convert some office buildings into housing or hotels.

More residents and visitors would make the neighborhood more dynamic and better able to support restaurants, shops and nightlife, said Griffin, executive director of the privately funded Downtown Center Business Improvement District, a nonprofit coalition of more than 2,000 property owners.

“If we trade some office for residential, that’s a good thing.”

The pandemic’s blow to the office market “is an opportunity that none of us ever imagined happening,” Welborne said, “transforming office buildings into residential buildings and reimagining our entire downtown.”

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.