How many people die each year in jails and prisons? No one knows

On the Shelf

Death in Custody: How America Ignores the Truth and What We Can Do About It

By Roger A. Mitchell and Jay D. Aronson

Johns Hopkins: 328 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The Los Angeles County jails had a particularly deadly year in 2023, with 45 people dying in custody. There were at least nine drug-related deaths, three suicides, three homicides, one death following signs of hypothermia and several cases where the cause has not yet been determined. By year-end, the county’s jails proved deadlier than they were just before the pandemic, when the incarcerated population was much higher.

Yet the fact that we even know these things makes Los Angeles different from many other municipalities, where jail deaths aren’t announced in news releases or posted online. That work is often left to zealous attorneys, nosy reporters or occasional oversight committees. And as Jay D. Aronson and Dr. Roger A. Mitchell explore in their 2023 book, “Death in Custody: How America Ignores the Truth and What We Can Do About It,” the lack of data is a national problem. In short, though some counties or states track it well, no one really knows exactly how many people across the country die in jails and prisons each year. This intricate investigation by Aronson and Mitchell details how things came to be this way. In an interview, edited for length and clarity, the authors explained to The Times why that matters.

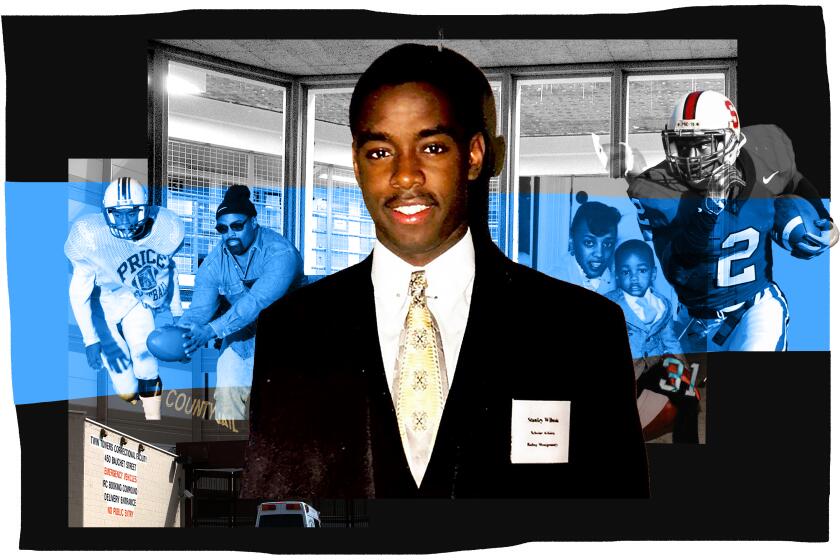

Like his father, Stanley Wilson Jr. played in the NFL and battled drug use and mental illness. The father found redemption. But could anything save the son?

Right now, the Los Angeles jails have been under a lot of scrutiny for their high death toll, but how does L.A. compare to other places?

Jay Aronson: The huge problem is we actually don’t know. To start with, there’s a lack of systemic data collected about deaths in jails — there was a period of time when the Department of Justice actually did know the number of people who were dying in particular facilities. But the government isn’t collecting that data at the moment. So we literally don’t know at a national level whether Los Angeles County is an outlier or whether it’s normal.

As your book explains, the reason the DOJ knew how many people were dying was because of the Death in Custody Reporting Act. Can you explain what that is?

Roger Mitchell: [It] is federal legislation that required jails and prisons to report deaths in custody. That data was tracked by the Bureau of Justice Statistics starting 2001, but the original law sunsetted in 2006. The BJS continued to capture data and was doing a pretty good job for several years. Then in 2013 an updated law was passed, with a clause that issued a penalty for law enforcement agencies that did not provide the information on deaths in custody.

JA: And that created a problem because the BJS don’t have the authority to collect statistics that are specifically used to enforce laws. So once there was a penalty for not providing the data, the BJS was no longer allowed to collect it. After 2019, they had to give data-collecting authority over to the Bureau of Justice Assistance, which is a grant-making entity. And in 2022, Senator [Jon] Ossoff’s subcommittee and the Government Accountability Office together found that the BJA numbers left out at least 1,000 jail and prison deaths in 2021. So the federal government is missing a huge number of deaths.

Jay D. Aronson and Roger A. Mitchell are co-authors of the 2023 book “Death in Custody.” (Kevin Lorenzi, Carnegie Mellon University/Jeff Suggs-Jeff Suggs Photography)

Why don’t we count them better? What is the resistance to, say, sending data to the federal government?

JA: We get asked that a lot. What we always come back to is that we as a society don’t care about the people who are in jails and prison. We associate them with people who are morally deficient. We boil people down to their worst moment. And we as a society are trained to believe that the people in jail or prison are there for public safety and that we’re somehow safer because these people are not in the streets. We have built this system because we have othered a particular group of people.

I do think that there’s a major change underway, and that younger generations are much better educated about these things. You can see that in the willingness to be critical of the criminal legal system. Also, while Black women are more likely than white women to be incarcerated, white women are the fastest growing population of people that are incarcerated in this country. Maybe when enough white women have died in custody we might get to a situation like we have gotten to with opioids, where we’re willing to recognize the humanity of people who are incarcerated.

The trove of jail security footage was released after The Times and Witness LA asked a federal judge to make the videos public.

Would simply knowing the numbers actually change policies or practices?

RM: The reason why we know how many cancer deaths are associated with smoking is because there’s a smoking checkbox in the U.S. standard death certificate. Jay often says that collecting data on deaths in custody is just the beginning of the process. Once we know how many people are dying, where they’re dying and under what circumstances then we can start developing comprehensive prevention strategies.

Are there specific states that handle in-custody deaths better or worse than others?

RM: California is way behind other states with its vestiges of the sheriff-coroner system. A coroner system is where the coroner is the highest official in the death investigation. They are often elected and do not require any medical degree or background in forensic pathology. A sheriff-coroner system is one where the coroner is also the sheriff.

A medical examiner system is one where that head person is a board-certified forensic pathologist. Usually the chief forensic pathologist at the helm of that system has 5 to 10 years of experience prior to ascending to the chief role.

The sheriff-coroner system is an antiquated system — coroners really don’t have the means and mechanisms to understand diseases or injuries. It has no place in our legal death investigation system, and when we’re talking about deaths in custody the sheriff has a built-in conflict of interest.

When a death occurs in custody, the sheriff-coroner has the ability to change the cause and manner. San Joaquin County is the best recent example of that. In 2017, the forensic pathologists there — both of them — quit because the sheriff-coroner was changing their death in custody cases from homicide to accidents or undetermined. That led to an audit, and I did that audit and made recommendations that the system there should be turned into a medical examiner system because that is best practice. California should move away from sheriff-coroner systems.

But Los Angeles doesn’t have a sheriff-coroner system, right?

JA: Correct. It has a medical examiner system.

Keri Blakinger was a promising young figure skater. One bad turn led to addiction and incarceration. The journalist discusses her memoir, ‘Corrections in Ink.’

There’s a common perception that a half-century or a century ago, jails were harsher or less evolved. Do we have any way of evaluating whether that’s true, or whether people were dying in custody more frequently then?

JA: We have anecdotal evidence or bursts of data that suggest that jails were harsh places back then. And although the facade of jails has changed, they are still deadly places. The likelihood of certain kinds of death — like suicide — have decreased, but jails have always been deadly and remain deadly. Prisons, too. For most of our history we don’t have a great way of tracking deaths in custody unless there was some journalistic effort or oversight entity — or if prison officials noted those deaths in meetings.

I know I just connected jail conditions and jail deaths — but do deaths in custody actually tell us anything broader about the system?

JA: They’re a signal that highlights a tremendous amount of suffering and pain and abuse that stays just under the surface when there isn’t a dramatic event like a death. Every single death tells us something important and if we see multiple deaths of the same kind then we really know that there’s a problem. That’s one of the big messages that we try to get at in the book: This is a national problem that requires the federal government to intervene by collecting the data systematically across the country.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.