Unsealed surveillance videos show violence against inmates inside L.A. County jails

In one of six videos made public as part of a court case about jail violence, L.A. County sheriff’s deputies punch an inmate repeatedly in the head.

In one video, a jailer kneels on an inmate’s neck. In another, two deputies slam a man’s head into a wall. In yet another, two jailers punch a handcuffed inmate repeatedly — even after he’s fallen to the ground.

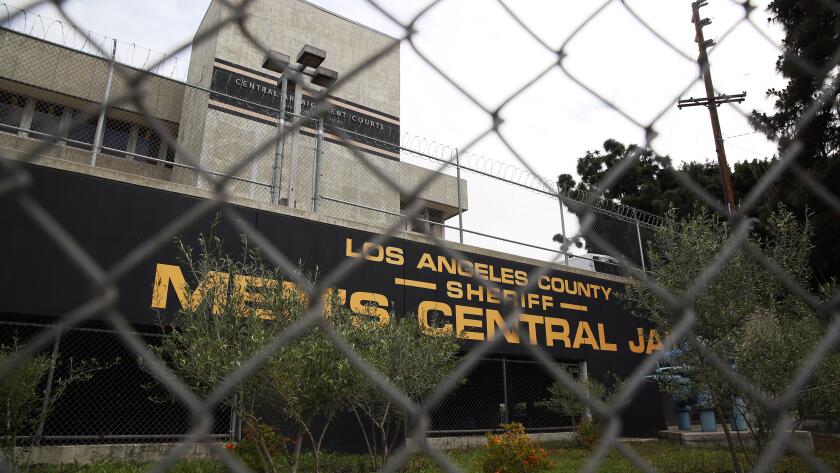

A new trove of surveillance videos from inside the Los Angeles County jails offers a rare view of the culture of violence that has persisted behind bars despite a decades-long federal lawsuit and years of jail oversight.

The release of the six videos comes months after The Times and independent news site Witness LA asked a federal judge to make them public. Lawyers for the county fought to keep the footage confidential, but after a hearing this fall, U.S. District Court Judge Dean Pregerson ordered the material to be released.

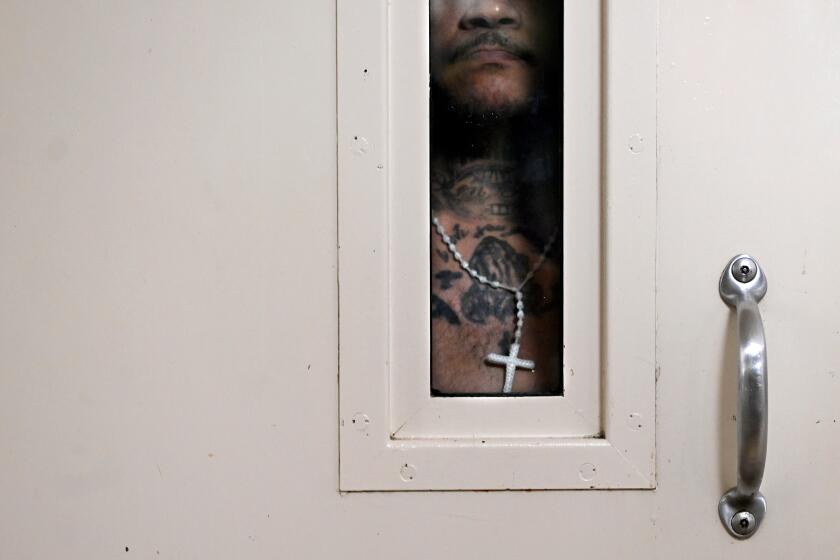

Such visual documentation of use-of-force against inmates typically remains unseen by the public, as most jail videos are protected from disclosure.

Before turning over the videos, the county blurred the footage to conceal the identities of staff and inmates. All but one of the clips are silent. Most are short, and it is impossible to know what came before or after the incidents shown. The shortest is 14 seconds. The longest is just over 15 minutes.

What is visible are several incidents in which deputies overpower men who are restrained. In only one instance does an inmate — in handcuffs — appear to kick at two deputies who are behind him. They punch him in the head, wrestle him to the ground and continue punching.

Masoud Rahmati’s death after an apparent pre-dawn beating has renewed concerns about supervision in L.A. County jails, which have seen at least three homicides this year.

Though federal court filings show that county jailers kick and punch inmates less frequently than they used to, the videos indicate the department has not fully reined in the use of force that spurred a lawsuit more than a decade ago.

In a lengthy statement, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department said it was aware of Pregerson’s decision to unseal the videos and called their disclosure “an opportunity to build further trust within the community it serves.”

The incidents in the videos “are not representative of interactions between deputies and inmates in the Los Angeles County Jail system,” the largest in the U.S., the statement said. “The videos that have been unsealed represent six of the millions of interactions that occurred over a more than two and one-half year period between October 24, 2019 (the date of the earliest use of force incident depicted) and July 4, 2022 (the date of the most recent use of force incident depicted).”

Peter Eliasberg, chief counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, said the videos show “unnecessary force in a variety of different guises.” The “most brutal,” he said, was a 14-second clip in which “two deputies take an incarcerated person out of his cell and then proceed to throw him headlong into either a concrete wall or a plexiglass wall.”

He said that video — previously obtained by The Times — depicts an “absolutely unnecessary” use of force for which “there’s clearly no justification.” The inmate “does not do anything to them. And frankly, even if he had, it’s almost impossible to justify that kind of force.”

Dated July, 2022, it is the most recent video released. According to the Sheriff’s Department statement, in that video, “the actions of the deputies are currently being scrutinized by the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office at the request of the Department for possible criminal prosecution.”

Another video that raised red flags for ACLU attorneys shows a deputy kneeling on an inmate’s neck. The deputy later wrote in a report that he acted “inadvertently” — a description Eliasberg disputed, asserting that an inadvertent action does not last nearly a minute.

Videos showing staff using force against inmates in Los Angeles County were released as part of a court case. A correctional officer kneels on a jailed man’s neck.

“This gentleman did get disciplined for putting knee to neck,” Eliasberg said. “He did not get disciplined for dishonest reporting. … Dishonest reporting is cancer to the operation of a law enforcement agency.”

A Sheriff’s Department spokeswoman said “appropriate administrative action was taken” after the incident but would offer no further detail.

In four of the six videos, Eliasberg said, he did not believe the deputies involved were disciplined. Sheriff’s Department officials did not offer clarification, and the department statement did not address that.

The statement did point out that deputies in the county’s jails work under difficult circumstances and often deal with people who have been accused of violent crimes.

“There has been a complete cultural shift away from the days when such abuses were tolerated,” the statement said. “Sheriff Luna is intent on building on that progress comprehensively, and at a more rapid pace than his predecessors.”

The videos came to light as part of a long-standing lawsuit over use of force against inmates in the Los Angeles County jails. The suit, now known as Rosas vs. Luna, began in 2012 when inmates accused deputies of “degrading, cruel and sadistic” attacks. Many of the incidents, the suit alleged, were “far more severe than the infamous 1991 beating of Rodney King.”

In Men’s Central Jail, they say, there is almost always something burning. But there are no smoke alarms where inmates live.

After three years of legal wrangling, the inmates, represented by the ACLU, and the county came to an agreement about specific changes the department would make to cut down on the number of beatings behind bars. Though records show there has been some progress toward that goal — including a 20% reduction in use-of-force from 2021 to 2022 — outside experts and ACLU lawyers say the department has yet to fulfill the requirements of the 2015 settlement.

Deputies still punch inmates in the face at a rate of just under once a week, according to court records. And jailers have been making use of a controversial full-body restraint known as the WRAP, which encases inmates in a blanket-like device from their ankles to their shoulders. Last year, an investigation by the news outlet Capital & Main found that the device had led to several lawsuits, and that safety claims about its use were based on anecdotes.

Given those and other ongoing concerns, earlier this year the inmates’ lawyers asked the county to make some changes to its plan to reduce use-of-force behind bars. These included the creation of a revised WRAP policy, mandatory-minimum punishments for deputies who violate certain use-of-force policies and a ban on deputies punching inmates in the head except in situations that could require deadly force.

To show why they believed those changes were needed, ACLU lawyers submitted several videos of jail violence, along with internal department reports.

Aside from footage of the punching and kneeling incidents, one of the videos shows a person bleeding on the ground and moaning and deputies employing the WRAP device to subdue him. ACLU attorneys raised concerns about the fact that deputies covered the man’s face in a spit mask — used to prevent people from spitting — while he was bleeding heavily. Medical exams later found that he had sustained an orbital bone fracture.

Because most of the videos — except for one that was previously reported on by The Times — had been given to the ACLU under a protective order as part of the lawsuit, the civil rights group wasn’t allowed to share them publicly.

The brutal 20-minute clip is one of a few dozen graphic videos saved to a thumb drive picked out of the trash by one inmate, and later secreted out of the jail by another.

When the organization’s lawyers decided to attach them to their filing as evidence, they did so under seal.

The Times and Witness LA filed a motion to have the videos made public, arguing in a September federal court hearing that they merited different consideration than other material the Sheriff’s Department gives the ACLU because they’d been filed as evidence of troubling allegations about ongoing violence behind bars.

The county said releasing the videos could create security problems, such as revealing where cameras are located inside the jails. But when the judge questioned whether the cameras were concealed, attorneys for the county admitted they were plainly visible.

The attorneys went on to say that releasing the videos could endanger the privacy of deputies who work in the jails. They also raised concerns about whether the videos would be taken out of context. Ultimately the judge decided to order the videos blurred and to allow the parties to provide written context for the released footage.

Since the ACLU submitted the videos to the court several months ago, the inmates’ lawyers have continued to negotiate with the county over changing some Sheriff’s Department policies inside its jails. During a hearing in October, the two sides said they had agreed on a new WRAP policy to curb use of the device.

But Eliasberg told the court he was still worried about the department’s “continued pattern” of finding uses of force — including punches to the head — to be justified and within policy even when court-appointed monitors who reviewed the incidents did not.

A bill in the California Legislature would add uniform rules about when solitary confinement can be used in jails.

The county and the ACLU have still not come to agreement on an updated policy restricting how often deputies can punch inmates in the face. The ACLU has pushed for banning such “head strikes” except when deadly force is necessary. Lawyers for the county have advocated for keeping in place a policy allowing head strikes whenever a deputy faces the threat of serious injury.

At a hearing in September, the county’s lawyers stressed that such blows only make up about 2% of all use-of- force incidents in the jails.

“The videos and the monitors’ continued reporting make clear that there is need for a more restrictive head strike policy to make sure that head strikes are used only in the most exceptional circumstances and to make sure that staff are disciplined appropriately,” Eliasberg said. “There is still a major problem.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.