For new refugees, finding work and housing is hard. Finding community is even harder

Carrying only two backpacks with clothes, important documents and baby formula, Abdul Jalil Barati, his wife and their 4-month-old son crammed into a U.S. Army aircraft with other Afghans at 1 a.m., ready to leave behind their family and friends for a new life.

It was Aug. 19, 2021, and as the Taliban took over Afghanistan in the wake of the U.S. military’s withdrawal, Barati — a former interpreter who worked with the Americans — made the difficult decision to leave his home to keep his wife and children safe.

“You can’t explain the feeling ... it’s a really bad feeling to leave everything behind,” he said.

Barati and his family flew from Qatar to Washington, D.C., New Mexico and then Southern California, where service organizations helped set them up with temporary housing and employment.

In the two years since Barati and his family fled Afghanistan, he and his wife — who have master’s degrees in fine arts and business, respectively — have had to start over. At one point, Barati held two jobs at a grocery store and an Arco gas station. He now manages the gas station and convenience store, and has given back to the nonprofit that helped him.

But he’s still working on finding community, something that many immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers struggle with in the weeks, months and years after arriving in the U.S., even in places with immigrant populations as large as the Los Angeles area’s.

“Statistics show that it takes an average of seven years for immigrants to become independent and integrated into American life,” said Anne Thorward, co-founder and president of Newcomers Access Center in Claremont, which helped Barati find housing.

Since the passage of the Refugee Act in 1980, the United States has admitted more than 3.1 million refugees, who get help from nonprofits with the first steps of integrating into their new community: finding housing and employment, learning English, feeding and clothing their family, and applying for eligible public benefits such as the 12 months of medical coverage from the Office of Refugee Resettlement.

But finding social groups, connecting with others, and feeling safe in their new neighborhoods aren’t often top of mind for refugees or the U.S. government.

Instead, when assessing the successes of resettlement in this country, the United States measures economic indicators such as real earnings and economic progress to gauge how quickly a refugee has become self-sufficient, said Nili Sarit Yossinger, executive director of Refugee Congress.

That limited focus on economic viability fails to capture the refugee’s full human experience, Yossinger said.

“You don’t suddenly feel like you’re a part of the community and you’re doing just fine just because you check the box on [economics],” she said.

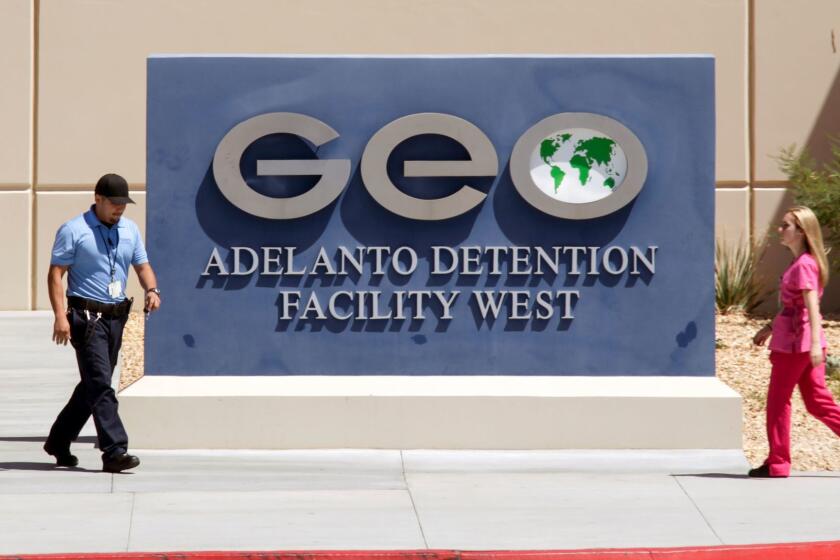

Unionized workers at the ICE immigrant detention center in Adelanto are urging the federal government not to shut it down.

Integration is critical to the success of the United States resettlement program, but how it’s measured lacks “direct feedback, guidance and leadership from those with lived experience in forced displacement,” according to a recent report by Refugee Congress and Refugee Council USA, which conducted a year-long research project on how refugees and asylum seekers adapted to life in the U.S.

The report’s six indicators for successful integration were English language acquisition, jobs and livelihood opportunities, access to continued education, access to healthcare and mental healthcare, housing and home ownership, and identity and inclusion.

“Forcibly displaced people wish to feel seen in their community, appreciated for differences, acknowledged for contributions, recognized for skills and able to share their stories of displacement and resilience,” the report stated.

As Barati got himself on solid footing in the U.S., he found it fulfilling to give back to his new community by working with Newcomers Access Center.

Over a year ago, the then-manager of the Arco gas station where Barati now works went to Thorward and asked whether any of the nonprofit’s participants needed work; Thorward referred Barati.

The sadness and bitterness I heard from elderly relatives about the takeover of our homeland conflicted with the lessons my parents tried to instill.

“It was either the same day or the next day, but you called me and said, ‘I start work tomorrow,’” Thorward said to Barati.

Now managing the gas station, Barati tries his best to return the favor by reaching out to Thorward whenever he is hiring. He wants to help give new arrivals work, he said, because he understands their need to provide for their families — and themselves.

“I succeed because somebody helped me, so I want to help others,” he said.

Barati has hired four refugees, including Hanna Hnatova, a civil engineer from Ukraine who fled with her two daughters in 2022 immediately following the Russian invasion.

A couple of months after getting on a plane from Ukraine to Madrid and then Mexico City, she walked with her daughters to California’s southern border and asked for asylum in the U.S. With the help of the humanitarian organization Nova Ukraine, Hnatova and her two daughters were eventually sent to Newcomers Access Center.

Though her daughters easily made friends with children at school, Hnatova said she is having a hard time making friends. There aren’t many Ukrainian families in the Claremont community, and the three that she met through the nonprofit live in Los Angeles or Thousand Oaks.

Hnatova is also still processing her harrowing journey, which included hiding underground with other families while the war was breaking out above them, sharing temporary housing with other families in Poland and the lack of communication with the relatives she left behind. Her parents are in Russian-occupied territory in southern Ukraine, so she’s lucky if they get to connect over the phone once a month.

Sometimes Hnatova wonders if she made the right decision bringing her daughters to the U.S. with no family or friends for support. The family is slowly meeting others, taking small trips in California to get familiar with their new home.

To help families like Hnatova’s meet others, groups such as Newcomers Access Center organize events and opportunities for recent immigrants with shared experiences to come together.

Amid grueling negotiations between senators and the White House, the contours of a bipartisan border security and immigration deal are taking shape.

The nonprofit Welcoming America created the Welcoming Standard, a framework with seven benchmarks for governments and organizations to use when resettling new immigrants: civic engagement, connected communities, economic development, education, equitable access, government and community leadership, and safe communities.

In Canada, the government uses social metrics such as the number of friends a refugee has, community engagement, healthcare needs and volunteering opportunities to measure integration, according to the report by Refugee Congress and Refugee Council USA. Unlike the United States, Canada’s program holds that integrating refugees requires involvement from both the newcomers and Canadian-born citizens, and it offers easily accessible newcomer services to help with more than just finding employment — including daily life, finding a mentor and language training.

For Carmen Kcomt, who came to the United States from Peru 20 years ago and is the director of the victim assistance program at La Maestra Community Health Centers in the San Diego area, the idea of community means helping those who find themselves newcomers to the U.S. as she once was. If she has extra canned food, she’ll set it aside to give to someone in need. She is always looking in her closet for clothes she can donate to clients or asking friends if they do.

A first-of-its-kind survey of more than 3,300 immigrants nationwide confounds some of the conventional wisdom surrounding their politics and partisanship.

As an attorney and former university professor in Peru, Kcomt often wondered if she made the right decision by uprooting herself and her sons.

But if she had to define what community she feels she belongs to, she said there are several — the immigrant, Latino, Asian, advocacy, and San Diego communities.

“When I was in Peru, maybe, I never thought about community because I was part of that country,” she said. “At the beginning of my four years waiting for asylum [in the U.S.] I felt like I wasn’t part of any community.”

That started to change, Kcomt said, when she went to Survivors of Torture International in San Diego with her two sons seeking safety.

There, she found a community that helped her — and that’s when she realized she felt a sense of belonging and an urgency to give back.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.