Don’t let anybody diss L.A.’s reading habits. This was and is a bookstore boomtown

It’s late 1937, and you’re F. Scott Fitzgerald, the once-celebrated writer, and you’re getting paid $1,000 a week, which, especially during the Depression, and even for the gilded coffers of MGM, isn’t toy money.

From your place at the Garden of Allah apartments on Sunset, in what is now West Hollywood, you might decide to amble the couple of miles to Hollywood Boulevard, to the Stanley Rose Book Shop, knuckled right up against Musso and Frank. There, you might find other scribblers, with names like Saroyan and Steinbeck, to share a convivial drink nearby; some of Hollywood Boulevard’s many bookshops are open almost as late as the bars.

Or you’re Ray Bradbury, and on a late April day in 1946 — April the 24th, if you must know — you head downtown, to Booksellers Row, centered on 6th Street between Hill and Figueroa. You’d get there by bus or Red Car, or on your bicycle, because you do not drive, not even one single block, not since you saw that gory accident about 10 years earlier.

You walk into Fowler Brothers bookstore, which opened in 1888 as a church supply shop, and by the time it would close its doors for good in 1994, it was the oldest surviving bookstore in the city. On that day, a brilliant and fetching book clerk named Maggie McClure caught his attention; Bradbury caught hers because she thought he was shoplifting books into his vast trench coat. They married not quite 18 months later.

L.A. is a universe where you can twinkle in the galaxy of your choosing — farming, tech, academia, movies, and, for much of the 20th century, bookshops. Whole solar systems of bookstores — new, used, rare, secondhand, antiquarian — clustered in certain cities: in Glendale, along Brand Boulevard; on Ventura Boulevard in the Valley; in Pasadena, on Colorado Boulevard, from Old Town to Vroman’s, still the oldest book-seller in Southern California; on and near Hollywood Boulevard; in Long Beach, orbiting around the legendary Acres of Books, founded the year after the 1933 earthquake, with miles of shelves where Bradbury went to shop, even though the science fiction section bore the label “screwball aisle.”

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

L.A. in the 1920s and ‘30s was beginning to shake off its reputation for hayseed Babbittry, or at least to acquire a critical mass of urban sophisticates possessing expansive tastes and sometimes the wallets to indulge them. The Zamorano Club, a men’s group named for the man who brought the first printing press to California, welcomed bibliophiles, oenophiles, foodies, collectors, art patrons, conversationalists, and tastemakers. Colleges and universities needed libraries to match the reputations they wanted to attain — and bought accordingly.

The movie studios needed research libraries so directors and producers could find out what Daniel Boone wore and what Cleopatra ate, and those libraries had huge budgets and farsighted librarians. California historian Kevin Starr once wrote that Jake Zeitlin — a pioneering rare-book seller and publisher — calculated that over 20 years, MGM alone spent $1 million bulking up its library.

Department stores ran book departments as big as modern-day bookstores, and in its column “Gossip of the Book World,” The Times let readers know when authors were due in town for book signings. Amelia Earhart would be at Robinson’s on Aug. 8, 1932, signing copies of her book “The Fun of It,” and as a bonus, her Lockheed-Vega plane had been dismantled, brought downtown from Burbank, and reassembled right in the store.

If you’ve seen the great 1946 L.A. noir film “The Big Sleep” — and if you haven’t, shame on you, go watch it at once, after you’ve finished reading this — one scene may have eluded your notice: Humphrey Bogart as Philip Marlowe walks out of one bookstore and heads right across the street to another, in search of a particular book, just as a rainstorm gears up. It is the rainstorm, not two neighboring bookstores, that was the Los Angeles rarity.

The 65 essential bookstores of L.A. County: Their vibes, customers, books and testimonies from customers, writers and owners.

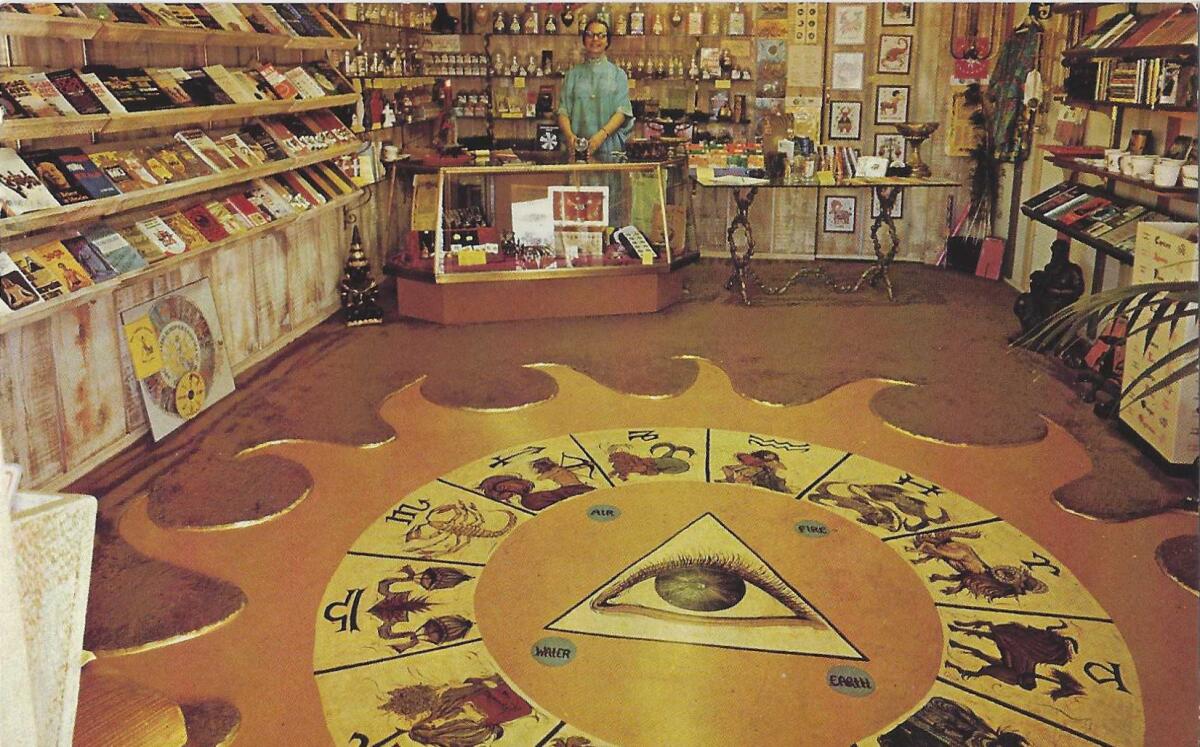

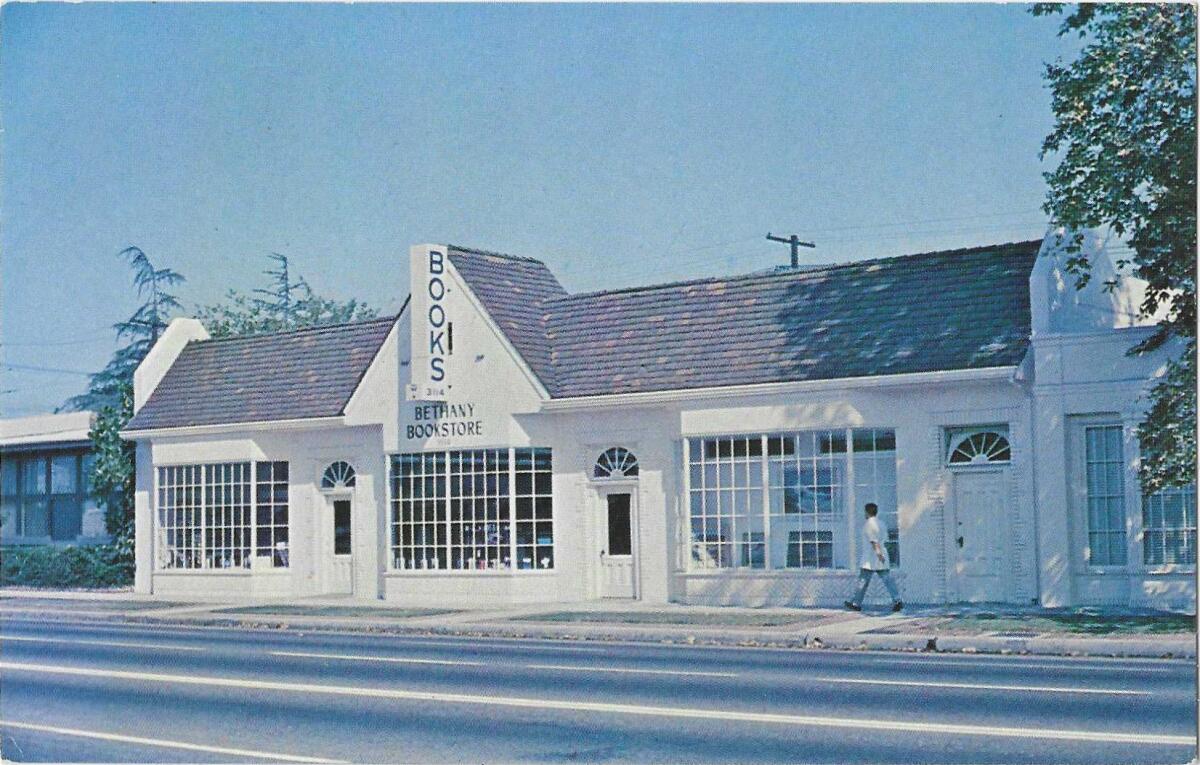

Even without today’s enticements of fluffy coffees and lounging sofas, book lovers of yore managed to endure the rigors of strolling from store to store in these neighborhoods. And, like moons to the bigger stores’ planets, specialty bookshops found bibliophiles’ markets for volumes about art, fitness, science, ethnic interests, photography, erotica, comics, sports, mystery and horror, architecture, and the spiritual. The glorious Bodhi Tree on Melrose Avenue was founded in the groovy year of 1970, extolled by Shirley MacLaine’s autobiography in the 1980s, and put out of business in 2011 by the usual suspects: online book sales and metaphysical books going mainstream in chain bookstores. The Thomas Bros., makers and sellers of those seminal Southern California map guides, once had stores in Los Angeles and in Long Beach — killed off by GPS and by a consequent public indifference to knowing all by yourself which way is north.

Beyond its Hollywood mother ship, Pickwick Books, in its flush years, operated branches in Canoga Park, Costa Mesa, San Diego, San Bernardino, Bakersfield, Montclair and on the Palos Verdes Peninsula. Dutton’s books reached readers in North Hollywood and Brentwood. The Martindale’s chain flourished in Century City, Santa Monica, the Wilshire District and in Beverly Hills, where its clientele was so flossy that the store carried Paris Match and an Arabian-horse magazine.

Fowler Brothers’ last move was to 7th Street, among the department stores and high-end shops. Fowler Brothers had sold books to Charles Lindbergh, Bobby Kennedy, John Philip Sousa, Irving Stone and of course Ray Bradbury. Marie Leong worked there for something like 25 years, full- and part time, and loved it partly because the owners were a family, and so was the feeling of the store; “when I wanted to do something with my daughter, like something at school, they’d let me come in late or leave early — so nice.”

Fowler Brothers’ location seemed ideal. Judges and jurors came in on their lunch breaks, as did workers in need of office supplies. Weekends, downtown was still a desert, but the weekdays were hopping. And then L.A. started digging up the street for a subway. Customers couldn’t navigate their way through the chaotic breaks in the street and stopped coming. The sidewalk out front collapsed from a construction leak. “My boss said, ‘I’ve had enough; we have to close this,’ ” Leong remembered. And in March 1994, that was the end. Ray Bradbury made a swan-song visit on the last day.

Online book shopping tends to herd you further and further down a rabbit hole of your known tastes and shopping habits. Wandering through a real bookstore promises the element of surprise, and lets you discover and cultivate interests you never knew you had.

Phil Mason ran a used bookshop on Western Avenue, marked by a distinctive red door. Magnificent Montague shopped there often, on the lookout to add to his enormous archive of black Americana books and ephemera. Montague was the Los Angeles R&B disc jockey whose joyous catchphrase for some especially fabulous recording was “Burn, baby, burn!” In 1965, young men and women took up Montague’s chant with a different meaning during the Watts riots.

Mason once assured me that he was the only registered monarchist on the L.A. County voter rolls. After he died, his books were sold off at a dollar each. I made two trips there, buying all that my yellow Civic hatchback could hold, and slowly driving my treasures home.

In Pasadena, there’s a boutique coffee place, part of a chain, where Prufrock Books once stood. As a poor student, I yearned after its treasures and still wonder what became of a book I coveted fiercely, one whose title I’ve forgotten but which had been signed by all of the Hollywood Ten.

As happens so often, just when something has almost vanished, we rediscover its virtues. So it promises to be these days, with new independent bookstores bursting upon us in Pasadena, Santa Monica, Highland Park. Barnes & Noble, originally the superstore scourge of independents, must be hoping for a joyous and prosperous welcome when it returns to Santa Monica next year.

It’s a delight to see all of these, of course, but the city can’t ever regain the deep bench of booksellers so many had before the Internet Age. Certainly since then, L.A. has registered often, by many metrics, as the biggest book-buying market in the nation, undented by the arch mockery from that 212 island.

A guide to the literary geography of Los Angeles: A comprehensive bookstore map, writers’ meetups, place histories, an author survey, essays and more.

We have serious readers now, as we had before — and we had the serious antiquarian bookshops for them and for serious collectors. In 1969, The Times described the ambience of Zeitlin and his partner’s legendary rare bookshop in a red barn on La Cienega as “that of a cathedral or a museum, or at least a temple for culture with a capital ‘c.’ ” Just a few years before he died, in 1987, Zeitlin sold 144 illuminated manuscripts, some dating to the 700s, to the Getty Museum for $30 million.

Their store names are still redolent of the aroma of fine books and manuscripts, of old paper and ink and leather on their vanished shelves: Caravan; Argonaut; Heritage; Aquarian Book Shop, the oldest Black bookstore in town. A few, like Heritage books and Michael R. Thompson, still do business, but by appointment only, on private premises.

And then we come to Dawson’s, once the oldest bookstore in the city. Michael Dawson is a third-generation Los Angeles bookseller from the celebrated antiquarian book and photography sellers. It’s been a family business since 1905, and still is, with appointment clients only since the Larchmont store closed in 2010. In those great ages of L.A. bookshops, “every bookseller sort of knew each other. There was the [Larry Edmunds] film bookshop [still on Hollywood Boulevard.] I worked for Heritage bookshop in the late ‘70s before they moved to La Cienega, then to Melrose, then closed. It was a very active community.”

Rare booksellers published catalogs of their treasures and sent them to their mailing lists of collectors. Collectors came to them with wish lists for the booksellers to track down.

And then, said Dawson: “The thing that was really hard for the out-of-print book trade was the advent of the internet.” Sites like AbeBooks made it easy for people who “were looking for books at the best possible price. That made bricks-and-mortar shops less competitive.” The online sellers didn’t have to factor in overhead or as many employees, for example.

In the pre-internet age, “that one book you wanted that was out of print, that you might have gone to Chevalier to find — now you can find a hundred copies online instantly and you pick the cheapest one.” Dawson’s got online early, “and for about two years there was an uptick in our business. We were selling about $15,000 a month.” Then came a downturn, as more people calling themselves booksellers appeared online — “You just need a room and a hundred books. The value of everything just declined.”

Even rare books declined in value, because they might not have been so rare after all. “Some things you thought were always going to hold their value, but you go online and you see 10 copies of something you used to consider rare,” he said.

Los Angeles’ first documented smog attack — yes, we had smog attacks — was in 1943. We’ve been fighting the sources of pollution and the quirks of geography that trap it ever since.

Dawson’s buyers “were always more or less collectors,” who “really valued the book as an object, not just for information.” He hopes — just a hope, mind you — that there’s a glimmer of this in people who grew up with the internet as their bookstore. He hears anecdotally that “they are intrigued by the book as an object. They enjoy the tactility of it. They don’t just want an e-book.” Similar to the people buying vinyl records again.

But there just aren’t many shops like Dawson’s around for them anymore. “I have thoughts about 30 or 40 years from now, people would pay money — like a cigar bar — for a place where you could go sit in an armchair and take an 18th century book off the shelf, one bound in leather, with rag paper — and live the experience of being in a rare bookshop.”

For that is the kind of thing that a bookstore must offer these days to survive — like downtown’s Last Bookstore’s slumber parties: not just a book, but a book experience.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.