As a third-grader at Grape Street Elementary School in Watts, Marveon Mabon introduced himself thus: I’m going to be president of the United States.

He was a Black boy growing up poor in Imperial Courts — the fourth generation of his family to live in the public housing development.

One day, a teacher lingering in the hallway, after hearing the child talk about the White House — where Barack Obama then lived — gave what she thought was a reality check.

Aim lower, the teacher said.

“Somewhere like McDonald’s or Taco Bell,” Mabon recalled her saying.

He was crushed.

A few years later, at the Watts Empowerment Center, a gray cinder block recreation center in the middle of Imperial Courts, Mabon confided in Justin Mayo: He still wanted to be president.

Mayo, the center’s executive director, took the child seriously. He sat with Mabon, and they wrote down the requirements for the job: Candidates must be 35 years old, a natural-born citizen, a resident of the U.S. for at least 14 years.

Mabon, now 20, said that conversation and his time at the center set him on a path out of the projects.

Too often, Imperial Courts — long troubled by gangs, violence and poverty — draws headlines for tragedy.

But at the Watts Empowerment Center, Mabon said, magic happens every day.

Talking about the center, Mabon quoted the adage: “You can’t pull yourself up by the bootstraps if you don’t have boots.”

For kids like Mabon, the place quite literally handing out those boots was the Watts Empowerment Center.

It also doled out clothes and food and school supplies. And, most important, hope.

:::

In August, the Los Angeles City Council approved $363,000 for the Watts Empowerment Center through the city’s new municipal anti-discrimination agency, the Civil + Human Rights and Equity Department.

The money, which is to be used to expand after-school programming at the center, will be distributed through a pilot program called Los Angeles Reforms for Equity and Public Acknowledgment of Institutional Racism (L.A. REPAIR) that focuses on impoverished communities.

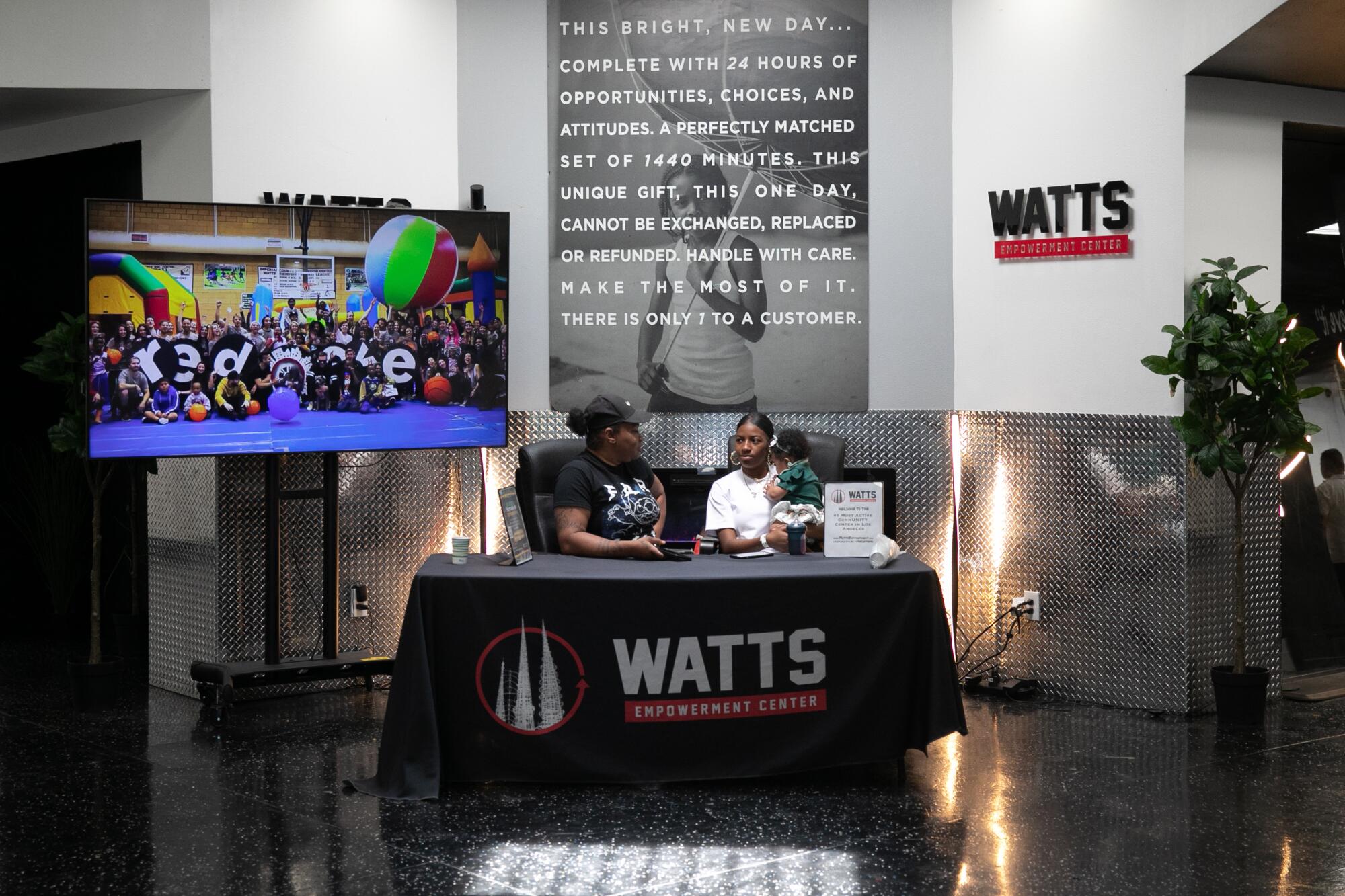

The Watts Empowerment Center stands right in the middle of Imperial Courts, a collection of squat apartment buildings with faded teal-colored cinder block walls and bars on the windows.

The housing complex is home to about 1,500 people, most of whom are Black or Latino.

Compared with the aging housing units, the rec center is huge and modern. It’s 12,900 square feet, with a hardwood basketball court, learning lab, culinary arts kitchen and recording booth for kids to drop their own tracks.

It bustles with children — some of whom stay away from their own challenged homes as long as possible — until late in the evenings.

The Watts Empowerment Center is run by philanthropist Justin Mayo, a blond, bespectacled white man whom Imperial Courts residents nicknamed White Chocolate.

The recreation center used to be run by the L.A. Department of Recreation and Parks. Built with city funds — and plagued by construction delays from the very beginning — it briefly shut down in 2017 because of a lack of public funding.

Mayo’s nonprofit, Red Eye, took over and reopened it as the renamed, renovated Watts Empowerment Center in early 2018.

Parks: Work began in 1998 on project that sits 25% complete as the city battles West Hills contractor. Residents blame City Hall.

Mayo — whose family founded the prestigious Mayo Clinic nonprofit hospital system 159 years ago — turned the rec center into a star-studded place.

Kim and Kourtney Kardashian and Kris Jenner attended the center’s 2018 reopening. Justin Bieber later came and engaged Imperial Courts residents in a push-up contest.

Logan Paul, the professional wrestler and YouTube influencer, played Santa for a Christmas toy giveaway. And Markus “Notch” Persson, the creator of the “Minecraft” video game, donated workout equipment.

Kids made a game out of guessing whom Mayo would bring in next and Googling volunteers’ net worth or the movies they starred in.

Mayo chalks up the center’s success to his willingness to ask what residents want rather than assume their needs.

“It’s easy to think of long-term plans, but I’ve come to learn in Watts that people need immediate assistance,” Mayo said.

For years, Mabon was at the Watts Empowerment Center just about every day.

There, he learned a lesson from Mayo: “Surround yourself with people you want to be like. But also be sure to actually build a relationship with that person.”

:::

Mabon — whose parents, grandparents and great-grandparents lived in Imperial Courts — wanted to be the first in his family to go to college.

That would mean defying the odds. In the densely populated South L.A. census tract that includes Watts, just 7% of residents have a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared with about 35% statewide.

Mabon grew up bouncing from apartment to apartment in Imperial Courts, where he lived with his single mother and eight siblings.

Even before a pair of shootings nearby drew attention in late July, the Imperial Courts public housing project in Watts had seen a lot of death.

His mom worked as a certified nurse assistant, a bus driver, a security guard. She did everything she could, Mabon said, to make sure her kids’ childhood was better than her own.

But sometimes the refrigerator was empty.

Still, Mabon always felt loved — and it took him a long time to realize his family was poor.

He said his godmother, Cynthia “Sue” Cain, “taught me that I was growing up in struggle and I wouldn’t always have what I wanted.”

As a teenager, Mabon was an honor roll student and student body president. He played baseball in the dusty field behind the rec center, started a community garden in Imperial Courts, founded an anti-bullying program at his school.

:::

Among those who looked out for Mabon and other Imperial Courts kids was Lavell “Yang” Grant.

Grant, who is a grandfather at age 35, was in prison for robbery from 2010 to 2015. Now, he runs day-to-day operations at the Watts Empowerment Center.

Even on his off days, Grant — with his raspy voice and ever-present ball cap — often helps oversee staff, most of whom are current or former Imperial Courts residents like himself.

His nickname, “Yang,” symbolizes light and masculinity in Chinese philosophy. In a community where young people often feel abandoned, he said, just showing up every day for them makes a difference.

He helps keep peace with the cops; often he has young people shadow him, teaching them how to navigate day-to-day interactions that could mean the difference between life and death.

“Imagine you’re playing with fire, but you trying to do right,” Grant told The Times. “It’s a cold balance to try and figure out while on the streets.”

U.S. Postal Service workers say they increasingly face violence and intimidation while delivering the mail.

Watching children at the center “take ownership of programs, own up to their mistakes, doing what they need to do — it’s wonderful,” he added.

One year, Grant told a group of kids that if they didn’t ditch school and consistently showed up for programs at the center, he would arrange for them to have a party bus for prom.

When the bus pulled up to pick up dozens of teenagers from the Watts Empowerment Center, the youths shrieked with joy. So did their parents.

Grant made sure some of their parents who were incarcerated got photos of their kids all dolled up in dresses and tuxedos.

“It was, like, one of my best days,” he said.

Mabon said he was endlessly inspired by “people like Yang, who’s been to prison, who’s been through the mud to hell and back,” now pushing for the extraordinary.

Mabon and Grant developed a tight bond in Grant’s “Boys 2 Men” group, an etiquette training program for young men in Imperial Courts.

Grant started the class by teaching participants how to button up a shirt. The next week, he taught them how to tie a necktie. Eventually, he provided full suits that kids could wear to big life events, like weddings or funerals.

“I wanted to let them know how it is to wake up every day and feel like you’re about business,” Grant said.

The class culminated in a visit to then-Mayor Eric Garcetti’s office. Mabon, who was in high school at the time and attended every week, was star-struck.

For Mabon, though, the most memorable moments were walks with Grant.

The two often walked for hours, lapping children playing on the concrete outside the rec center, discussing Mabon’s goal to get out of the projects and become a politician.

“If you’re really about this,” Grant told him, “do what you gotta do — and I got you every step of the way.”

If not for the daily conversations with his mentors — Grant, Mayo, his mother and his godmother — Mabon said he probably would have done just what that elementary teacher told him to do: aim lower.

:::

Before his senior year at Alain Leroy Locke College Preparatory Academy, Mabon and Cain, his godmother, spoke often of his dream of attending a historically Black college.

Cain died from ovarian cancer on Valentine’s Day in 2021.

That spring, Mabon was accepted to prestigious Morehouse College, a private, historically Black men’s school in Atlanta.

But, according to Mabon and his mentors, he was denied financial aid and scholarships because his prep school did not send in the proper paperwork on time.

He initially thought he couldn’t afford to attend Morehouse, where annual tuition, room and board cost about $50,000 — more than double the Black median household income in Watts.

Watts rallied around him. Volunteers who had worked with him started a GoFundMe drive called “Let’s Make Marveon a Morehouse Man!” It raised nearly $91,000.

Mabon, however, arrived in Atlanta for the fall semester in 2021 feeling “overwhelmed” and longing for home.

The pressure of a new environment, lack of a support system and death of his godmother provoked a period of depression and doubt.

He returned home months later, feeling like a failure, calling the experience “the worst year ever,” he said.

An Imperial Courts resident reminded Mabon that he could always join a gang if college didn’t work out.

Grant, standing within earshot, yelled back in anger.

“Don’t you put that energy in the air!”

Mabon, he knew, belonged in college.

:::

Mabon is now a junior at Morehouse, where he is majoring in sociology.

He knows the ’hood is rooting for him, because the first response he often gets during visits home is: “Why are you here? How can we get you back to Atlanta?”

It’s heartwarming. But comes with a lot of pressure.

Inspired by Fannie Lou Hamer, officials imagined a micro economy of urban farms after taking stock of the community gardens that sprouted in Los Angeles with little to no investment.

“I don’t want to disappoint people who’ve gotten me here and who’ve believed in me,” Mabon said. If something doesn’t go right for him, he has tended to not tell people about it “because I want everything to be perfect.”

“I’ve always had it in my head to be great, excel, be excellent,” he said.

Mabon interned this summer for L.A. City Councilmember Tim McOsker and currently is interning for U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-Ga.).

Mabon still remembers that elementary school teacher telling him to aim for a future at McDonald’s. Last year, the fast-food giant chose him as one of the McDonald’s Future 22 — a campaign spotlighting young Black leaders.

He still wants to be a politician — and help out people back home in Watts.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.