In a Watts housing project, ‘a death angel’ kept knocking this summer

Even before the shootings last month that drew the attention of politicians and police, gang interventionists and longtime residents, the Imperial Courts public housing project in Watts had seen a lot of death.

On July 1, Brenda Slocum succumbed to lung cancer. She was 63.

Five days later, her son, Rodney “Rah-Rah” Richmond Jr. — who grew up in Imperial Courts and still stayed there often — died of a heart attack, just after celebrating his 38th birthday. He was reeling after his mother’s death.

On July 10, yet another Imperial Courts resident, Dwight Lockett Jr., 43, died in an automobile crash. That week, another neighbor in the complex died of cancer.

By late July, when a pair of shootings in Watts killed two people and injured seven near Imperial Courts and the nearby Jordan Downs housing project, grief prevailed. In the words of one resident, Cynthia Mendenhall, a “death angel” kept knocking on people’s doors.

“Oh, Jesus,” she said as she considered the losses. “This is a lot.”

Imperial Courts, a collection of squat apartment buildings with faded teal-colored cinder block walls, is home to about 1,500 people, most of whom are Black or Latino.

It is essentially a small town. And every death — by natural cause or tragic circumstance — hits hard.

“In the Watts area, we’re dying left and right,” said Summer Spicer, tears on her cheeks.

Slocum was her mother; Richmond her brother.

Violence in Watts prompts calls for unity in the community as gang interventionists partner with law enforcement and faith leaders.

Spicer said the recent wave of death at Imperial Courts, which was built in 1944 to house factory workers during World War II, is not limited to those who have found themselves “caught up at the wrong place at the wrong time.”

For generations in South Los Angeles, home to some of the city’s most impoverished and polluted neighborhoods, poorly treated chronic illness — like heart disease, high blood pressure, lung cancer, diabetes, depression — has been rampant.

Sorrow is so ingrained in the psyche that children in Imperial Courts joke that the word Watts is an acronym: We Are Trained To Survive.

“Been a lot going on,” said Tim Lee, 17, about the recent violence in the neighborhood where he has lived all his life.

“I’m an out-of-the-way kind of person,” he said. “Just trying to stay out of trouble. Trying to stay safe.”

Read the full series on disease, inequity, resilience and love in South L.A.

At a news conference earlier this month, community leaders and gang interventionists advised residents of the projects not to congregate in large groups for the rest of 2023.

Mayor Karen Bass said in a statement that she met with the Watts Gang Task Force — a volunteer group of residents, police officers, politicians and representatives from local schools and nonprofits — after the shootings. Through “collective action,” she said, “we will work diligently to ensure our young people and their families feel and are safe.”

On July 16, a gunman killed Raysheun Gordon, 30, and injured four other people near an Imperial Courts parking lot, according to the Los Angeles Police Department.

On July 29, a gunman opened fire on a group of people watching a sporting event at Jordan Downs, a mile north of Imperial Courts, police said. Kyimonte Johnson, 19, was killed, and three others were injured.

According to the Watts Gang Task Force, disrespectful posts on social media likely played a role. The shootings remain under investigation, according to the LAPD.

The gunfire was a tragic — and frustrating — coda to a cruel July in Imperial Courts.

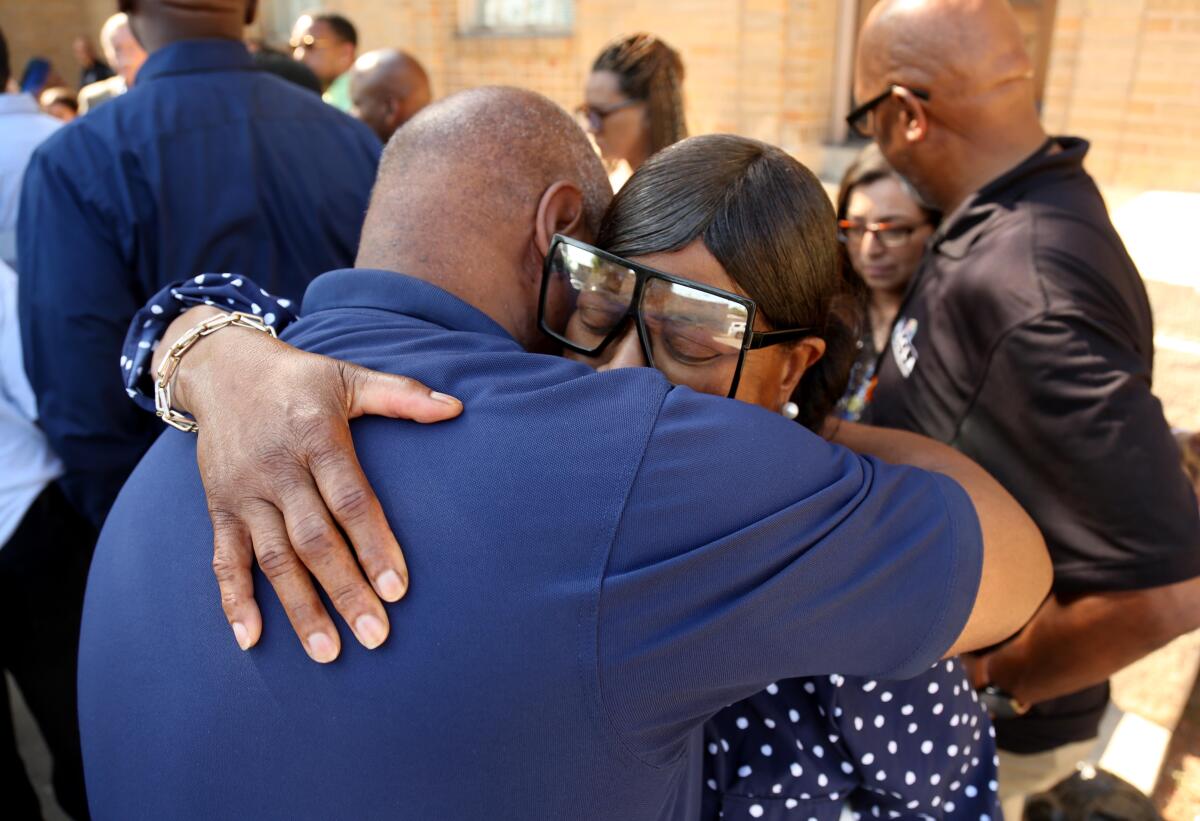

Surrounded by pastors, politicians, police officers and OGs, or original gangsters, at a healing circle in the complex, Dwight Lockett Sr. mourned the loss of his son, who died in a crash near Gaffey and Channel Streets in San Pedro.

“My community loved my son,” Lockett said. “They took care of my son. I grew up here and I seen many things happen, but when it” — meaning death — “come knocking at your door, it’s a wake-up call.”

A few days later, Spicer recalled her youth in the housing project with her late brother, Rah-Rah, who told her in the days after their mother’s death that he “wouldn’t make it.”

“He was Imperial Courts,” she said.

Richmond was a jokester whose laugh rang out from the recreation center in the middle of the complex. Even as an adult, he could often be found in a parking lot in Imperial Courts, hanging with his childhood friends.

Spicer, 47, and her brother spent many hours watching “Gilligan’s Island” as kids. And, in a way, she said, Imperial Courts was like their own personal Gilligan’s Island: It seemed like visitors could come and go, but a lot of residents could never leave.

Spicer, a mother of three, moved out of the project in the early 2000s, but, like so many who grew up there, she finds her way back often and now works for the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles, which oversees Imperial Courts and other low-income housing.

Amid the grief, she and others said, there is a pressing need to focus on joy in and around the 490 units that make up the complex.

It is, after all, a home.

After the July prayer circle, children shrieked, chasing each other in a game of tag near the slide and broken swings of the Imperial Courts playground, which sits on the corner of 114th Street and Gorman Avenue.

Each passing car prompted a wary look from the large group of men who laughed in a circle nearby.

For years, residents have been talking about moving the playground — which is exposed to the streets — to the center of the complex so children would be protected by the concrete walls if bullets start flying.

The violence that has long plagued the projects, Spicer believes, stems from a lack of guidance from parents and families.

“I never sit here and judge these kids on how they do it, because ain’t nobody else telling them how to do it right,” she said.

“If you are diligent and come in wholeheartedly caring about these kids, you’ll plant that seed. Then it’s up to them to let it grow and spread to others.”

Feeling a sense of community and love, she said, went a long way when she was growing up in Imperial Courts.

“Everybody was family. Aunties. Cousins. We’d barbecue together, and in a time of need, we’d have gotten together and been there,” she said. “I think we need to get back to that.”

Recent backpack giveaways hosted by the nonprofits Sisters of Watts and Red Eye offered a glimpse of a blissful afternoons in Imperial Courts.

Lines stretched across the complex, with families hauling wagons and strollers, stocking up on school supplies, clothes and — at the Watts Empowerment Center on the grounds — pairs of Nikes, Vans and other popular kicks for kids to wear on their first day of class.

Some hid their prized possessions in Call Jacob backpacks donated by the law offices of Jacob Emrani.

“We have a lot of ups and downs, but our ups outweigh the downs.”

— Summer Spicer

Thinking back to a time when she herself trudged to the center of the projects to grab school supplies for herself and her siblings, Spicer smiled as she relaxed with three longtime friends in lawn chairs.

“Sometimes I feel like it’s so far gone,” she said. But the joy of that August afternoon is why she promises to always return to Imperial Courts, no matter how far away she finds herself.

“We have a lot of ups and downs, but our ups outweigh the downs,” she said.

She pondered aloud about what could end the sorrow that has afflicted the complex this summer and provide a little hope.

An upgrade to the aging apartments, with their fading paint and bars on the windows and doors, would go a long way, she said.

“Why can’t they make this place look like the rest of America with condominiums?” she asked.

And more jobs, of course, would help, she added.

Los Angeles City Councilman Tim McOsker, who represents the area, said the city has dozens of job openings and that he has been hosting job fairs and other events to steer renters into becoming 911 operators, crossing guards, sanitation workers or gardeners.

He said he also recognizes the need to engage young people who have credibility in the community and that he is working with the mayor to create paid positions for so-called ambassadors — people who can work directly with the younger generation to keep violence down.

“These would be individuals who are in the community, know the community, have license to operate in the community,” McOsker said. The hope is that they would “bring down the temperature” of ongoing gang-related disagreements.

Mendenhall — an Imperial Courts resident now called “Big Mama” who was called “Sister” when she was a gang member — says the situation in the projects is is not as chaotic as it appears from the outside. But she welcomes investment, of time and resources, to make it a better place.

Mendenhall helped institute a 1992 truce between gangs in Watts and is no stranger to grief.

She lost both of her sons months apart. Anthony Wayne Owens Jr. was shot Aug. 30, 2006, in a drive-by shooting in the 2000 block of East 115th Street inside Imperial Courts. His brother, Darin Cole, reportedly took his own life after a police pursuit Dec. 9, 2006.

Mendenhall now runs a program for children from broken families at Imperial Courts. During a job fair there this summer, dozens of young residents greeted her with a kiss on the cheek.

“All they want is a hug,” she said. “And to hear me say I love them.”

Times staff photographer Genaro Molina and staff writer Libor Jany contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.