Bill to restrict solitary confinement in California stalls out in Sacramento

SACRAMENTO — In a blow to criminal justice reform advocates and a win for corrections officials, California lawmakers delayed legislation on Wednesday to restrict the use of solitary confinement in prisons, jails and immigration detention centers, to buy time to negotiate with Gov. Gavin Newsom over safety concerns.

Assemblymember Chris Holden (D-Pasadena) agreed to hold Assembly Bill 280 in the final days of this year’s legislative session amid opposition from sheriffs and prison officials and skepticism from Newsom over its sweeping application and definition of segregated confinement, known as solitary. The legislation may be considered in 2024.

Democrats are divided over legislation to limit solitary confinement in California’s prisons, jails and private detention centers.

Last year, Newsom vetoed similar legislation to restrict solitary confinement, also authored by Holden, saying that while he believed the issue was “ripe for reform,” the proposal was “overly broad” in a way that could “risk the safety of both the staff and incarcerated population within these facilities.”

Newsom instead directed the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, or CDCR, to modify its rules on solitary confinement, currently being drafted and expected this fall. But the veto message did not include any directions for immigration detention centers or jails, facilities that Newsom does not control and where advocates say rampant abuse of solitary confinement is happening.

A bill in the California Legislature would add uniform rules about when solitary confinement can be used in jails.

Holden reintroduced the measure, arguing that legislation was the best way to ensure adequate changes to isolation practices in California. While he continued conversations with Newsom’s office over the bill, AB 280 was moving through the state Capitol with strong support from Democrats.

But negotiations hit a snag in the last few weeks. Though the Senate narrowly approved AB 280 in a 21-12 vote, Holden, in consultation with the coalition lobbying in support of AB 280, agreed to keep it pending in the Assembly until next year. There, it would have faced its final vote before going to Newsom and, what advocates feared, receiving another veto.

“No matter what a person has done, extended time in solitary confinement is torture, because it breaks their spirit,” Holden said during a Sept. 7 rally at the Capitol in support of AB 280. “The time is now.”

Holding it in the Assembly, Holden said, means AB 280 can still be used as a backup plan in the new year should CDCR’s regulations fail to address concerns.

“Maybe we celebrate [the guidelines],” Holden said in an interview with The Times. “But if we don’t, then the bill still can be used as a vehicle to make a change.”

Advocates supporting AB 280 called on Newsom to negotiate with them in “good faith.”

“Solitary confinement is torture and it must end. The governor has repeatedly attempted to undermine or gut [AB 280], in order to continue to torture thousands of people in California prisons and other detention sites, while worsening safety for everyone,” said Hakim Owen, an advocate who worked on the campaign to pass the legislation and an undergraduate at UC Berkeley’s Underground Scholars program for formerly incarcerated people.

“But our growing campaign, led by people who have lived through solitary or had family members inside, has continued to thwart [Newsom’s] efforts to marginalize our movement,” Owen said. “The people have spoken. The vast majority of legislators have spoken. And now the governor needs to join his own party on the right side of history.”

Newsom spokesperson Izzy Gardon said the governor’s office does not typically comment on pending legislation.

CDCR spokesperson Terri Hardy said that the new regulations will face public review and a hearing, and that there will be opportunities for public input. The rules, Hardy said, “will restrict the use of segregated confinement except in limited situations where individuals have engaged in violence or have serious safety concerns that cannot be handled otherwise.”

The delay is another setback for prison reform advocates who spent the last year and a half lobbying for new restrictions on isolation for prisoners. Last month, a federal court ruled to end supervision of a 2015 settlement agreement that restricted solitary confinement in California’s prisons. The agreement was prompted by a lawsuit and prison hunger strikes in protest of prolonged isolation.

The decision to hold AB 280 also reflects the challenges facing the progressive criminal justice reform movement in recent years, as concerns over crime — and criticism of Democrats’ approach to solving it — increase, and therefore complicate efforts to overhaul the prison system.

Inmates end California prison hunger strike

The proposal would limit solitary confinement for all prisoners to 15 consecutive days, or no more than 45 days in a six-month span. It would also prohibit its use not only for pregnant and postpartum women but also people with certain mental and physical disabilities, and anyone younger than 26 or older than 59.

Corrections officials would be required to increase out-of-cell time for recreation and rehabilitative programming, including counseling and treatment services.

The 15-day restriction wouldn’t mean that prisoners would automatically be placed back in what’s called the general population. Instead, advocates said the bill would require corrections officials to find alternatives to isolation that could involve placing someone in a unit that provides more meaningful human contact and access to services.

Law enforcement organizations, including the California State Sheriffs’ Assn., argued that the proposal would impose dangerous, costly and impossible restrictions on what they see as a vital tool to mitigate violence in their facilities.

Gov. Newsom vetoes bill to end indefinite solitary confinement in California, citing safety concerns

Gov. Gavin Newsom on Thursday vetoed a bill to limit solitary confinement in California’s jails, prisons and private detention centers.

“We don’t want people to be segregated beyond what is needed and/or reasonable. I agree with that. But we don’t do that,” said Tulare County Sheriff Mike Boudreaux, president of the association. “I just don’t see the need for this bill.”

Republicans consistently voted against AB 280, arguing that lawmakers should funnel their time and attention toward preventing crime.

“There are gangs inside of our prisons. And there is crime inside of the prisons that is perpetuated on populations there. And solitary confinement is a tool to manage the prison and keep that from getting escalated,” said state Sen. Brian Dahle (R-Bieber).

Several moderate Democrats also either opposed AB 280 or abstained from voting on it, and several questioned why the Legislature was sending Newsom nearly the same proposal as the one he vetoed.

“Should we pass a bill, as well-meaning as it is ... that sets an arbitrary limit? It doesn’t take into account the conditions in the prisons,” said state Sen. Steve Glazer (D-Orinda).

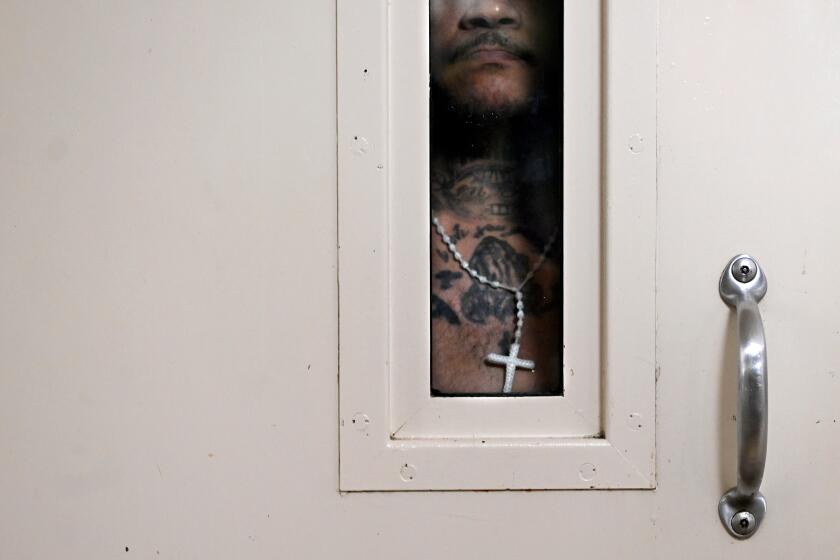

But for those who’ve lived through weeks, months and, in some cases, decades of prolonged isolation, they argue that solitary confinement is used to torture prisoners, and that its practice contradicts California’s politically progressive values.

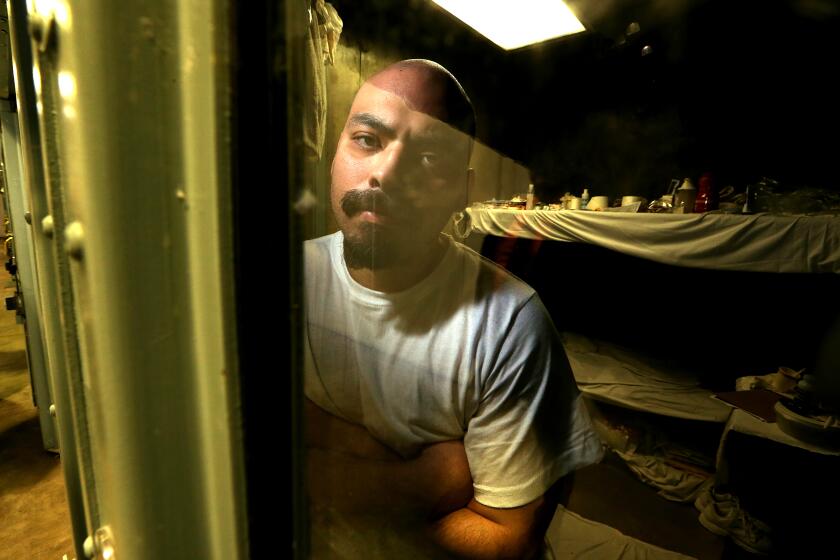

Eduardo Dumbrique, 42, traveled from Southern California to the state Capitol for the rally last week. Dumbrique said he survived 13 years in solitary confinement in California prisons before he proved his wrongful conviction for murder and was released in 2021.

“It was the worst experience of my life. I’m so grateful to be free today, but I’m also really struggling with the effects that solitary had on me,” Dumbrique said. “To say that I’m not broken wouldn’t be accurate.”

James Daly, a prisoner at San Quentin who spent more than two decades in solitary confinement in federal prisons throughout the country, said the experience was like “living within a tomb.” He is now serving a state prison sentence for the same crimes that landed him in federal custody, including robbery, kidnapping and attempted murder on police.

Daly said he remembers entering prison when his daughter was just a few months old, and not being able to hug or hold her again until she was 26. He would count the concrete air bubbles on his cell’s wall for entertainment, the opening and shutting of doors and the drag of shackles on the floor the only sounds he heard for years.

“Society as a whole has an interest in what goes on in those places,” Daly said in a phone interview with The Times. “That interest is that one day, many of those people are going to come home. Do you want someone who’s spent 20 years locked in a place like that?

“If you’re not angry going in,” he said, “you’re angry going out.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.