The fight to limit solitary confinement in California prisons is set to roil Sacramento again

FOLSOM, Calif. — On a recent day in this sun-soaked suburb, conditions were perfect for an outdoor workout at a maximum-security prison in Northern California.

Winter storms had turned the hills surrounding California State Prison, Sacramento lush green, and Maurice League was enjoying the view from his individual exercise yard, a caged plot of concrete not much bigger than a dog pen, during the roughly three hours a day he’s allowed outside.

“Now that the sun is coming out, the weather is very beautiful,” League said in between a round of burpees, pull-ups, squats and 1,000 push-ups. “We need that vitamin D.”

The fresh air was a welcome break from his 70-square-foot cramped and dimly lit cell in the prison’s disciplinary block where prisoners are housed in isolation for committing crimes while incarcerated. Among them: murder, attempted murder or serious bodily injury. Some belong to gangs, according to prison officials, or have enemies inside that require separation to avoid more violence.

Corrections officials call the unit “short-term restricted housing.” Advocates define it as solitary, or segregated, confinement, because incarcerated people spend nearly all day restricted to their cells with little human contact other than with prison staff.

The Los Angeles Times was granted limited access to the unit in mid-April, months after it first submitted a request for a tour and as a debate rages on in the state Capitol over legislation to restrict the practice of holding incarcerated people for up to 23 hours a day in small cells.

Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed the same proposal last year, saying that while segregated confinement was “ripe for reform,” safety concerns needed to be addressed. He then directed the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to draft a new set of regulations that would modify current practices without raising the risk of violence. The state agency plans to submit those draft rules by November.

Despite Newsom’s veto, Assemblymember Chris Holden (D-Pasadena) reintroduced the bill, arguing that without legislative intervention, the corrections department was unlikely to craft the kind of restrictions needed to safeguard prisoners against abusive prolonged isolation, which he said amounts to torture and leads to devastating mental health consequences.

“We’re not saying do away with solitary confinement,” Holden said. “But you have to structure it differently so that you’re not putting people in a situation where you’re treating them less than human.”

Gov. Newsom vetoes bill to end indefinite solitary confinement in California, citing safety concerns

Gov. Gavin Newsom on Thursday vetoed a bill to limit solitary confinement in California’s jails, prisons and private detention centers.

California State Prison, Sacramento is already home to those who’ve committed some of California’s most violent and serious crimes. Prisoners here have been convicted of murder, armed robbery, sexual assault or other violent crimes, said Associate Warden Chance Andes, who oversees the unit.

Incarcerated people housed in general population are allowed prison jobs and can move from place to place without being shackled. They spend hours a day in school or programs and have access to a prison yard with exercise equipment and a track where they can roam freely.

In segregation, prisoners are restrained and escorted by prison staff when they leave their cells. They’re allowed visitors and legal visits, but through a glass divider. They otherwise use tablets to stay in contact with their family via video.

Each week, they’re allowed outside for roughly 18.5 hours, plus 90 minutes for programs inside the prison. The rest of their time, approximately 21 hours a day, is spent in cells that come equipped with a toilet and bunk and where they’re directly provided meals.

Of the some 1,450 people incarcerated at California State Prison, Sacramento, 88 were being housed in the unit as of mid-April.

League was sent to “the hole” five months ago for battery, he said. At 46, he’s spent more than half his life in prison at different facilities, so he’s had time to build up a level of tolerance to the monotony during various stints in segregation. He was most recently sentenced in 2007 for two counts of assault with a semiautomatic firearm, plus other charges and enhancements that tallied up to 37 years, according to corrections officials.

He leans on his faith and family to get through the long days, he said, and loves to read.

“I’ve been doing time for a long time. I kind of more got used to it,” League said during an interview. “I just learned to draw on different strengths to where I don’t succumb to a lot of the loneliness and different things that can overtake some people back here.”

Deven Johnson, who is serving time for first-degree robbery, first-degree burglary and assault, was placed in segregation seven months ago, he said, also for battery. Johnson, 25, said he receives some of the same mental health help and services that the general population does, just in a more restrictive setting.

But he still misses the college classes he was taking before he was sent to confinement. He was studying sociology.

The programming and time outside is optional, which means those who refuse it might spend their entire day locked up.

Peter Azevedo, 36, prefers his cell tidy, with his mat rolled up on the concrete slab bed. He keeps a Bible and dictionary next to his bunk. He was sent to the unit in October but refuses yard time and group therapy sessions, he said, referring to himself as a “solitary individual.” Azevedo is serving a 13-year sentence for assault with force likely to produce great bodily injury, with an enhancement.

“I’m hanging in all right,” he said.

Fewer than 1,200 people, or 1.2% of California’s incarcerated prison population, were living in segregated confinement during a 2021 nationwide survey of prisons conducted by the Correctional Leaders Assn. and Yale Law School. The vast majority are men, and more than half are placed in confinement as punishment, according to the survey.

Those numbers don’t account for prisoners in segregated confinement in county jails and private detention centers. The Board of State and Community Corrections, which oversees county jails and juvenile detention facilities, does not collect statewide data on how many people are placed in segregated confinement.

Margot Mendelson, legal director for the advocacy nonprofit Prison Law Office, visits often with her clients in segregated confinement units in California’s jails and prisons and describes some of the conditions as “horrifying.”

California lawmakers pass a bill to limit solitary confinement stints in jails, prisons and detention centers, and to ban it for vulnerable inmates.

Units are often dimly lit, filthy concrete spaces where people lack access to basic amenities such as a “clock to know what time it is,” she said.

“The only real form of communication in many of these places is screaming through the door jam or through the food port, just in an effort to have some human communication,” Mendelson said. “So it is an experience of being caged like an animal at all times.”

Holden and the coalition behind Assembly Bill 280 point to those conditions as evidence for why regulations around segregated confinement are needed.

Known as the Nelson Mandela Act, named after the late South African civil rights activist who spent decades in prison, AB 280 would define segregated confinement as the holding of someone for more than 17 hours a day, either with a cell mate or alone, and with severely limited freedom of movement and human contact outside of prison staff.

It would end indefinite solitary confinement by limiting segregation to 15 consecutive days, or 45 total days in a six-month span, and ban its use entirely for those with certain mental and physical disabilities, pregnant and postpartum prisoners and anyone younger than 26 or older than 59.

The measure would also mandate stringent documentation for when and why segregated confinement is used, require more regular mental health checks on incarcerated individuals and increase the number of out-of-cell hours they’re allowed for recreation, meals and treatment.

The bill would bring California in alignment with the United Nations’ Nelson Mandela Rules, a document that advises against solitary confinement for longer than 15 days, after which it’s defined as torture.

The proposed changes have reignited a contentious debate in the Legislature, where lawmakers have spent the last decade approving laws to reduce the prison population through alternatives to incarceration. Advocates supporting AB 280 say restricting segregated confinement should be part of the broader movement toward rehabilitation and treatment and away from long-prison terms.

Gov. Gavin Newsom this week will announce plans to remake San Quentin, one of the state’s most storied prisons, using a Scandinavian prison model that emphasizes rehabilitation.

“At the end of the day, we want to see these facilities have a plan beyond isolation,” said Hamid Yazdan Panah, advocacy director for Immigrant Defense Advocates, one of the organizations supporting the bill.

Law enforcement groups reject that argument and say the restrictions on solitary confinement will lead to more violence in prisons. They contend that the state agencies overseeing prisons and jails, not the Legislature, are best equipped to regulate policies related to confinement.

State prison officials attached a staggering $1-billion price tag to last year’s bill after estimating the new restrictions would require additional programming space and an expansion of exercise yards and more staff. The union representing California’s prison guards, which has significant political sway in the Capitol, also opposes the legislation.

Ending years of litigation, hunger strikes and contentious debate, California has agreed to move thousands of state prisoners out of solitary confinement under the terms of a landmark lawsuit settlement.

“[AB 280] will also very likely eliminate the use of segregated confinement in a lot of situations, including when placement is necessary for the safety of the facility or individual incarcerated persons themselves,” Cory Salzillo, legislative director for the California State Sheriffs Assn., said during a recent hearing on the bill.

State Sen. Steve Glazer of Orinda, one of the few Democrats to vote against the original bill, introduced his own measure this year as a “middle ground” solution. The proposal would require the state prison agency to maintain more robust data on segregation and adopt standards laid out in a 2015 settlement agreement with Pelican Bay State Prison prisoners who sued the state after spending years in solitary confinement.

The settlement was supposed to end indefinite solitary confinement by limiting why and for how long individuals can be placed in isolation, but a judge has ordered continued oversight of the settlement due to concerns over compliance.

Column: Solitary confinement is shrouded in secrecy and open to abuse. Why does California allow it?

Prison officials have too much discretion in deciding when to use solitary confinement. California should demand they explain their decisions.

“I don’t like the unlimited time,” Glazer said. “And I also don’t think that putting that type of one-size-fits-all standard requirement on our corrections department will keep inmates and staff safe.”

The bill failed its first committee amid opposition from many of the same groups supporting Holden’s proposal. It was granted reconsideration, which means it can be brought up for another vote.

A main goal of AB 280 is ensuring access to the kind of mental health treatment and programs that lead to rehabilitation and give prisoners better odds for when they’re released.

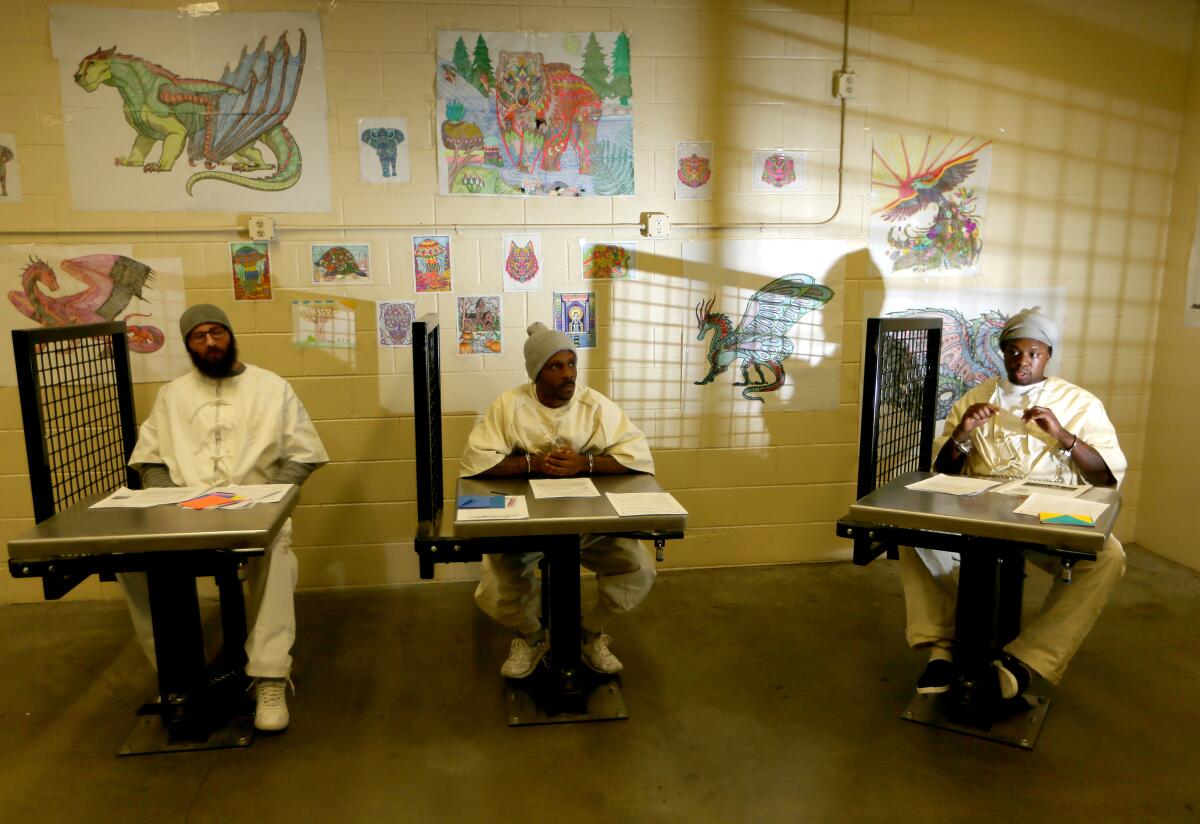

Earlier this month, during the hour and a half they receive in structured out-of-cell time each week, three men in the segregated confinement unit at California State Prison, Sacramento were reviewing an exercise on emotional resilience and coping skills.

The walls of the classroom were covered with art projects, portraits of bears, wolves and dragons colored in a kaleidoscope of geometric patterns. A clinician guides the men, their hands and feet shackled to their desks, through a discussion on building a strong support network.

For Javon Clark, 29, growing up in foster care made it easier for him to connect with people from place to place.

“I’ve been doing time before I’m doing time,” said Clark, who was sentenced to 17 years for assault with a firearm inflicting great bodily injury, plus a firearm enhancement.

Most of the incarcerated people in the unit have limited mental health needs and receive the lowest level of outpatient care. Those with more severe conditions, such as drug-induced psychosis or schizophrenia, are held in a more intensive unit that requires rigorous treatment.

The group therapy is a type of programming that proponents of AB 280 say can be made more effective with the legislation. They argue that keeping people locked up for hours is more costly and less effective than providing additional out-of-cell time for group activities and allowing people to maintain their prison jobs so they can pay restitution and spend their days on something meaningful.

“People need social contact to survive, to heal, to rehabilitate,” Yazdan-Panah said.

Lawmakers approved AB 280 during its first hearing on a 6-1 party-line vote. It now heads to a committee that evaluates bills that carry a substantial fiscal impact, where Holden is the chair.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.