Column: This is how to beat DeSantis in the endless, racist culture war over Black history

Tolani Britton and Travis Bristol, a husband-and-wife team of associate professors of education at UC Berkeley, possess the sort of pragmatism that I wish I had in these trying times.

Like so many of us in liberal California, they have watched with dismay as conservative politicians in other states have pushed through laws and policies designed to whitewash lessons about race and discrimination from public schools.

Books of fiction and nonfiction alike have been banned. Teachers have been told what they can and cannot say in classrooms and what facts and realities they must ignore, lest they be summarily fired.

Hours after the Florida governor announced his run for president, LeVar Burton of “Reading Rainbow” fame issued a stark warning about what’s at stake.

It’s a crusade that has only intensified in recent weeks with Florida, first, rejecting an Advanced Placement course on Black history for being too “woke” and, as such, lacking “educational value,” and then crafting its own curriculum, which includes an appallingly inaccurate assertion about “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

Stupidly, at least according to the latest polling of Republican candidates for president, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has repeatedly defended his state’s new curriculum, despite it clearly not resonating with voters. Meanwhile, Vice President Kamala Harris — along with a curious collection of MAGA-aligned Black Republicans — has repeatedly assailed it.

“They plan to teach students that enslaved people benefited from slavery,” she told a ballroom full of Black women in Orlando last week, during the Women’s Missionary Society of the African Methodist Episcopal Church Quadrennial Convention. “They insult us in an attempt to gaslight us.”

The back-and-forth is a mere microcosm of the culture wars ripping our country apart. Culture wars that many of us feel helpless to stop.

Which brings me back to Britton and Bristol.

For the last few months, the associate professors have been quietly building a team to create a new California-centric Black studies curriculum, based on the exhaustive research of the state’s first-in-the-nation reparations task force.

You might recall that the task force officially ended its work in June, amid much hand-wringing over how many billions of dollars might be requested of state government to compensate Black people for the lasting harms of slavery and systemic racism.

Lost in much of that was the sheer breadth and depth of the task force’s final report, with its detailed historical accounting of how the progress of Black people was repeatedly blocked and stopped by laws and policies that, for example, promoted mass incarceration and thwarted our efforts to build generational wealth.

Imagine, for a moment, students learning about the history of Bruce’s Beach in classrooms. Or the history of how Black and Latino residents were removed by fire to make way for what is today downtown Palm Springs.

“The goal is to put that education into the mainstream,” Britton told me one recent afternoon.

Indeed, both she and her husband hope their forthcoming curriculum will be adopted by high schools and community colleges. But because they’re pragmatic and because they see what’s happening in Florida, they aren’t counting on it.

Reparations, Black Panthers — no topics are off limits in this AP class on Black history. Pupils say they’re now more likely to vote and be involved in their communities.

So, instead, they plan to take the slightly unorthodox approach of making the curriculum free and accessible to the broader public, finding ways to distribute it to after-school programs, community groups, churches and parents.

Anyone who is in a position to teach a child about Black history, also known as American history.

To accomplish this, Britton and Bristol are bringing in — and paying — high school students, teachers and community educators to help develop the curriculum through a series of workshops and pilot programs.

“The pendulum always swings on what can and can’t be taught in schools. And we know that schools are not the only places of learning,” Britton explained, “particularly for Black children.”

This is how you win the culture wars — or at least undercut them.

It’s not necessarily a new idea. But it is one that seems to be gaining popularity as public school systems increasingly become focal points for partisan pettiness and racist power plays passed off as parental rights.

In Florida, for example, a group of Black religious leaders, civil rights activists and community organizers recently held a news conference via Zoom to announce that they are forming a task force to teach Black history in the state and opening a series of “freedom” schools.

“He’s not going to rewrite and redefine Black history,” R.B. Holmes Jr., pastor of the historic Bethel Missionary Baptist Church in downtown Tallahassee, said of DeSantis. “Not while we’re still alive.”

Such efforts might seem unnecessary in California.

We are, after all, one of only 17 states to expand education on racism, bias and the contributions of specific racial or ethnic groups to American history.

We’re also the first to require that high school students take at least one semester of ethnic studies. By law, the courses will start being offered in the 2025-26 school year and the class of 2030 will be the first that’s subject to the graduation requirement.

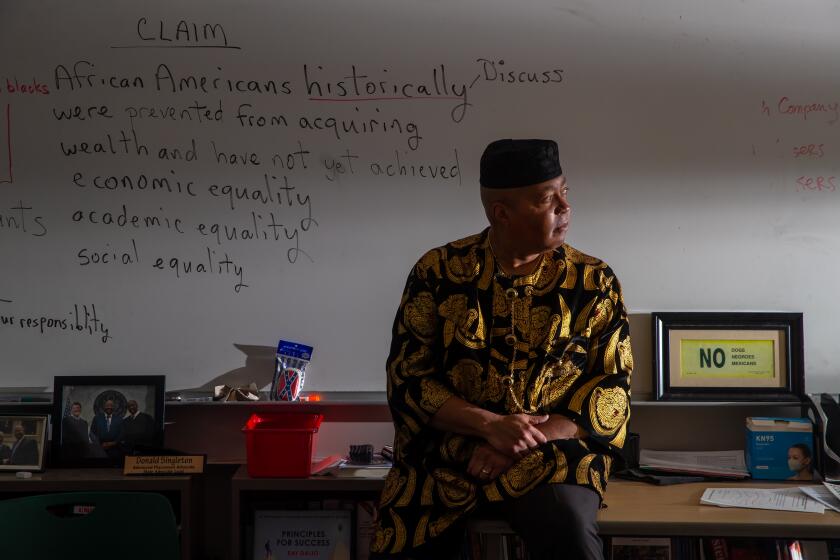

Meanwhile, as my colleague Howard Blume reported recently, 18 students at Dorsey High School in South L.A. were among only a few hundred students nationwide to take the College Board’s new Advanced Placement African American Studies course this past school year.

This is the same course that Florida officials, at the urging of DeSantis, rejected in favor of building a flawed curriculum of their own.

At a time when the GOP is trying to erase Black history, Jefferson Boulevard now highlights a history that has long shaped this city and its people.

Yet even in California, a few districts have followed Florida’s lead and passed bans on lessons about race and racism, usually described under the catch-all term “critical race theory.”

Among them is Temecula Valley Unified School District, which was sued last week by a group of parents and teachers for allegedly violating state laws that mandate lessons about racism, inequality and how past events are relevant in the present day.

“I do not believe that CRT or any racist ideology is a suitable educational framework for classroom instruction at the elementary and secondary level,” school board President Joseph Komrosky told The Times in what he described as a personal statement.

Unsurprisingly, Temecula is the same district that Gov. Gavin Newsom threatened to fine and send textbooks to after its board refused to adopt a state-approved social studies curriculum because it included lessons on slain gay rights leader and San Francisco County Supervisor Harvey Milk.

Eventually, the school board relented — but not before Komrosky called Milk a “pedophile.”

Trying times, indeed. Laws and policies are always changing, particularly in this political environment.

“Without trivializing what is happening currently, I think it has always been the case that students in different states and different districts, learn different things,” said Britton, who along with Bristol worked and studied in various states before moving to California.

“I think it is both the challenge and the opportunity of a decentralized school system that we have.”

This is why, even though California should absolutely celebrate the introduction of ethnic studies courses in public schools, and adopt that AP African American Studies course as soon as it is available, the lessons of Black history can’t be confined to classrooms. Nor to the whims of politicians.

That’s how culture wars are waged and ultimately lost.

“We have always known, in part because schools weren’t even always open to Black people,” Britton said, “that there are many, many places of education for Black children.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.