Mei Xing’s sex trafficking trial laid bare many secrets of the San Gabriel Valley’s massage parlors.

Each time a masseuse had sex with a customer, Xing collected $40. The masseuse typically made at least twice that much in tips.

Xing, who ran three massage parlors, could be a nasty boss, scolding or firing those who crossed her. Streetwise and strong-willed, she trusted no one. Yet she also socialized with many of the fellow Chinese immigrants she employed. At festive meals, they celebrated birthdays, a housewarming and the Lunar New Year.

Five of the women ultimately turned on Xing, telling the FBI she forced them into prostitution, then testifying against her at the trial in Los Angeles.

Now it was Xing’s turn.

Wide-eyed jurors watched her rise from the defense table — her ankles unshackled for the day — and swagger to the witness stand, her salt-and-pepper ponytail bouncing. The clop clop of Xing’s sandals pierced the courtroom’s silence.

In a loud voice, the stout defendant described in Mandarin how it all worked — the $40 fee, the tips, the tracking of the cash. She placed “Masseuses Wanted” ads to find sex workers for the downscale massage parlors she ran in strip malls on the wide boulevards of the largely Asian and Latino suburbs just east of Los Angeles.

Xing kept meticulous handwritten ledgers. Day by day, they showed which women worked at what time and how much was allocated to the house for each trick. Every employee, Xing said, was free to quit any time.

“I’ve never forced anybody to engage in prostitution,” she told the jury, a diverse group of men and women drawn from all over Southern California. An interpreter standing next to Xing captured her brassy delivery.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

It’s a gamble for any defendant to testify. Xing, 62, had little to lose. If the jury found her guilty of any one of the five sex trafficking charges, the mandatory minimum sentence would be 15 years.

Xing also had good reason to be hopeful. The government had produced almost no independent evidence to corroborate her accusers’ allegations. It was their word against hers.

Xing’s testimony, from a witness box framed by white marble, would leave jurors confronting uncomfortable questions at the end of the three-week trial in June.

Why might her accusers have lied?

At what point does commercial sex become involuntary?

Was Xing’s conduct as egregious as the government charged?

Sex trafficking, a modern form of slavery, is often conflated with commercial sex work, but is not the same thing. To win a federal sex trafficking conviction, prosecutors would need to prove that Xing used threats of force, fraud or coercion to cause a victim to engage in prostitution.

“Mei Xing was a madam, there’s no disputing that,” Xing attorney Neha Christerna conceded to the jury. “But she was not a trafficker.”

Xing’s hometown is Tianjin, a huge industrial port city 80 miles east of Beijing. Her mother was a doctor, her father a land administrator. Xing earned an associate’s college degree, then worked as a midwife at a Tianjin hospital.

She married Yuanjin Li, who would leave home for months at a time to work on fishing boats at sea, and they had a son. When Xing moved to the United States in 1997, she left the toddler with her mother in Tianjin.

“I wanted to make money in the U.S.,” Xing testified. “I wanted to have my family have a better life.”

Her son is now 30 years old and raising two kids of his own in China.

“So you’re a grandmother?” Xing’s attorney Callie Steele asked.

“Yes.”

In her mid-30s, Xing settled in the San Gabriel Valley. She divorced Li and married an American. She had a second son she would raise in California.

Xing found a job washing hair at a salon. She took on cooking, cleaning and childcare duties for a family in Arcadia. She gave foot and body massages at a medical clinic in the Little Tokyo neighborhood of downtown L.A.

Xing wound up getting hired at a massage parlor, then another and another — a half dozen in all. She and her co-workers often performed commercial sex, she testified.

“Did you do it voluntarily?” Steele asked.

“Yes,” Xing replied.

Xing was arrested on charges of prostitution and related misdemeanors in 1999. She pleaded guilty to lewd conduct. In 2001, she was arrested again and convicted of prostitution. In both cases, Xing offered sex to an undercover cop, according to her lawyers.

Like other Chinese immigrants doing sex work, she adopted an American nickname, “Anna.” At her massage parlors, Xing also came to be known as “boss” or “sister.”

With steady income, savings from China and an inheritance from her father, Xing bought a $385,000 condo in San Gabriel in 2011. She drove a black Mercedes E350 sedan.

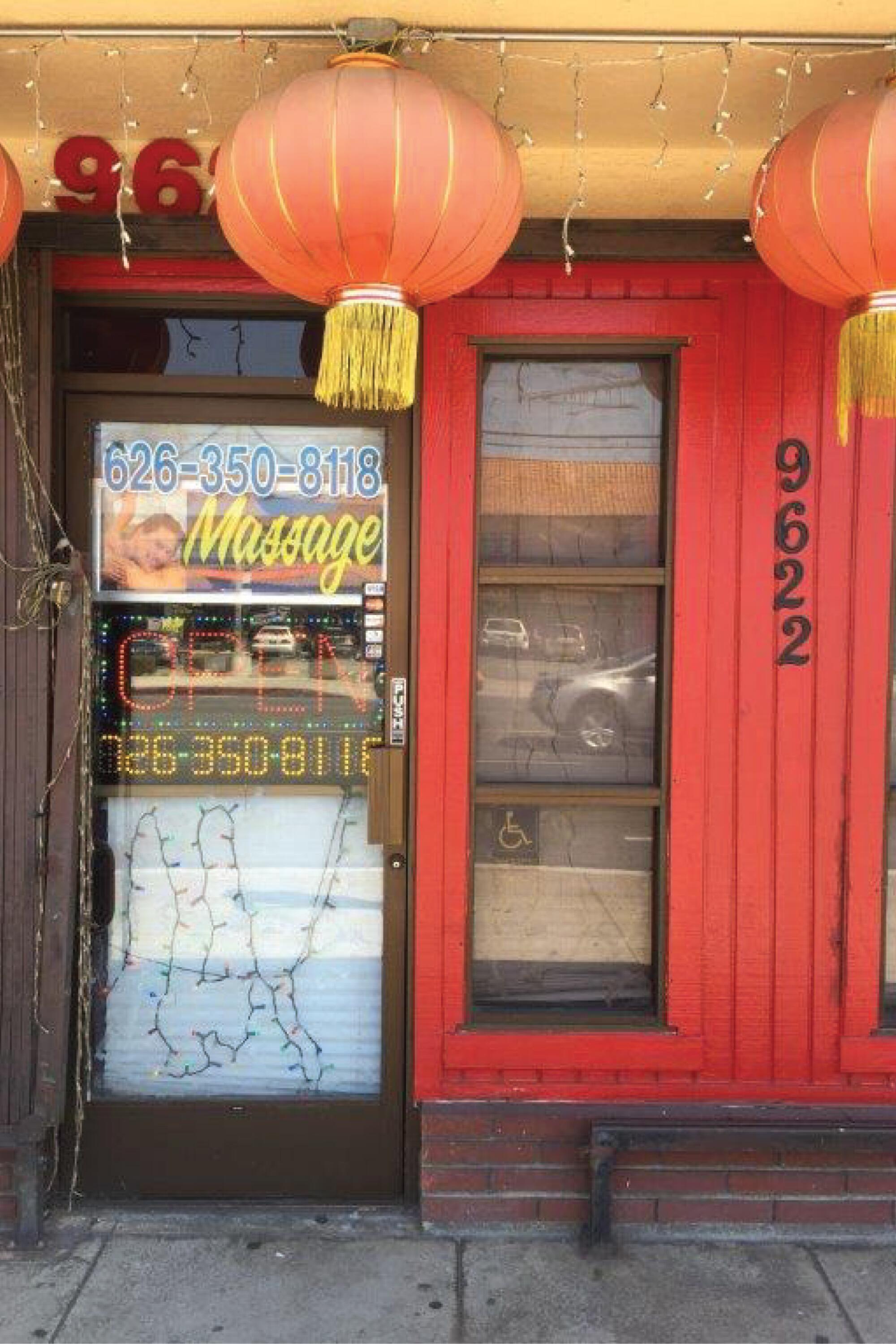

In 2013, Xing opened her flagship business, Sunshine Massage, in a strip mall on Garvey Avenue in South El Monte. Red oval lanterns with golden tassels hung above the entrance. A sign in the glass door showed a woman’s hands kneading the shoulders of a smiling man. The storefront was painted red.

Inside was a reception area with plastic plants and more Chinese lanterns. Along a dimly lit hallway were 13 private rooms with massage beds and mirrors on the wall. Masseuses sometimes gathered in a kitchen break room or smoked cigarettes just outside the back door.

“Massage parlor is hiring young beautiful masseuses, good tips, stable source of customers, massage license preferred,” said one of Xing’s ads on chineseinla.com, a site for local Chinese immigrants.

At first, Xing said, she strictly forbade sex, instructing the front-desk clerk to listen in the hallway for suspicious sounds. But some customers would leave if they couldn’t get sex, she told jurors, and the masseuses were flouting the ban anyway, so she decided to allow it.

Xing marketed the business accordingly. To attract customers, she placed ads with photos of young women in provocative poses on Backpage.com and other adult services websites. “Pretty young Chinese girl,” one of them said. “A lot of surprises, just waiting for you.”

The cost of a one-hour massage was $35, collected at the front desk upon entry. If the masseuse was licensed, Xing would pay her $15; if not, $10. Massage parlors can be shut down for offering sex, so Xing would remind employees: “We’re a massage parlor. We need to provide massage service.”

But a lot more money could be made in prostitution, an occupation fraught with risk. Xing’s accusers alleged several customers raped them. Sexual assault in the context of commercial sex is a crime, but nobody was charged in these cases.

A big concern at the massage parlor was the danger of police raids. Xing and “the girls,” as her attorneys called them, were on constant lookout for undercover cops. Condoms were hidden in Dior and Aveeno lotion bottles with false bottoms.

In 2016, a masseuse was arrested at Sunshine Massage for offering a “happy ending” by hand to an L.A. County sheriff’s deputy posing as a customer, Xing said.

Staff also kept guard for surprise city inspections. South El Monte required massage therapists to be licensed; many of Xing’s were not.

Tips for happy endings and oral sex were between the masseuse and the customer, Xing told the still wide-eyed jurors. Xing would just take her $20 or $25 share of the $35 entry fee.

Vaginal sex, known at Sunshine Massage as a “big job,” was a whole other matter. Xing would not only keep the entire $35, but also charge the masseuse $5 to ensure Xing got her full $40, she told the jury. The masseuse was expected to negotiate a minimum of $80 in tips she would keep.

All of the masseuses preferred sex work over massage, according to Xing, because the tips were so much higher. A masseuse who went by “Luna” testified she typically earned $6,000 to $7,000 in tips per month.

On a typical day with about 10 masseuses on duty, the receptionist would keep track of who clocked in at what time and assign them customers in that order.

A popular customer at Sunshine Massage was known as Brother Liu, a big spender who hired Xing to organize sex parties at a nearby hotel, several of the women testified.

“He was the super VIP of the massage parlor,” a former front-desk receptionist told jurors. She called him “very generous” with tips, saying “he just gave out money like paper.”

Liu wrote more than $84,000 in checks to Xing for supplying food, booze and women, an FBI agent told the jury. Liu sometimes liked to just talk, drink and dine with the masseuses. Other times, he had sex with one after another, two masseuses testified. One told jurors he pressured her into unprotected sex against her will.

Liu “drank beer nonstop,” Xing told the jurors. “I thought he was quite lonely.”

At first glance, Xing’s ledgers don’t seem to distinguish between a massage and sex.

But to those familiar with her system, the notations are simple to decode: $35 is massage, $40 is sex. Xing had no choice but to take it on faith — begrudgingly — that the masseuses truthfully reported what occurred in private rooms.

“I don’t really trust them,” she testified.

Xing was also wary of her partners. When Sunshine Massage closed in July 2017, she went into business with the owner of Garvey Therapy, a dingy massage parlor in a strip mall across the street. In return for bringing masseuses and customers there, Xing got a 30% share of Garvey Therapy.

That meant more than two thirds of every $40 house fee for sex would go to the other owner. Xing resented sharing profits, because she suspected her partner was trying to lure her customers away.

Her revenge — in cahoots with masseuses — was to cheat her partner by keeping a secret set of books, Xing admitted at the trial. Each masseuse agreed to put at least one trick on the covert ledger every day, allocating the full $40 house fee to Xing, the ledgers show. In 2018, while Xing was visiting her cancer-stricken mother in Tianjin before she died, masseuses texted her photos of the secret ledger pages via WeChat.

Not all the sex occurred at massage parlors or a hotel. Xing also opened a minimalist brothel on Garvey Avenue in Rosemead. It was another strip-mall business, this one with no sign on the door. Xing charged masseuses $40 each time they took a customer there and split the fee with an investment partner, she told the jury.

If the john wanted to maximize privacy, Xing — also for a $40 fee — would sometimes have the masseuse take him to her San Gabriel condo. She and her teenage son lived on the first and second floors. The third was set aside for business: A spartan bedroom and bathroom with a separate entrance.

Xing, who gave masseuses the door entry code, kept the space well stocked with lotion and clean towels. Tucked in the nightstand drawers were condoms and a pair of black high heels.

Nicholas Stewart, the lead investigator in more than 50 human trafficking cases, slipped his hands into blue latex gloves and picked up the evidence on the edge of the witness box.

“These are Sico condoms,” he told jurors, showing them what was seized from the nightstands.

Stewart is the Los Angeles County sheriff’s detective who opened the Xing investigation in July 2018. At the time, he was on the Los Angeles Regional Human Trafficking Task Force, which includes the Sheriff’s Department and the FBI.

The case was triggered by the Coalition to Abolish Slavery and Trafficking, a Los Angeles nonprofit that operates a hotline sex workers can call to report trafficking. The group’s leadership declined to discuss the case.

CAST took two women to see Stewart. Both said they’d engaged in prostitution at Xing’s behest while working at two massage parlors she partly owned: Rose Spa, on Peck Road in El Monte, and Garvey Therapy.

One of the accusers, who’d been fired by Xing after bringing drugs to work, made allegations that yielded no charges.

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

But the other would become one of the five accusers testifying against Xing at the federal trial. The Times is identifying her as Witness 1, because she says she was sexually assaulted and asked not to be named.

Witness 1 said Xing had threatened to tell police she was a prostitute if she refused to serve sex clients, according to a search warrant request filed by Stewart. She was scared, Witness 1 reported, because Xing had photos of her changing clothes or in the presence of condoms or massage parlor records.

But evidence that would impede the prosecution soon emerged. It turned out that Witness 1 had invested $10,000 in the Rosemead brothel; she and Xing were 50-50 partners. It would be unusual for any trafficking victim to share profits in a bordello with her trafficker.

The partnership did not last long. When Xing found out that Witness 1 was not reporting all of her tricks in the ledgers, they had a fight, and she left the business, Xing told the jury. Xing said she also fired Witness 1 from her masseuse job at Rose Spa.

Witness 1 warned Xing she would pay a price for letting her go, according to Xing. Payback, Xing’s lawyers would argue later, was the reason she falsely accused Xing.

Stewart got a search warrant for Garvey Therapy and Rose Spa, along with Xing’s car and condo. The raids took place on Oct. 23, 2018.

“The police officers made a mess of my house,” Xing testified.

Xing was arrested on state trafficking and pimping charges and interrogated at length by Stewart and an FBI agent. At the trial, Xing would admit she lied to them over and over, denying she hired masseuses to do sex work and claiming she knew nothing about any sex trade at her massage parlors.

Mei Xing is interrogated by an FBI agent and a Los Angeles County sheriff’s detective.

Four other masseuses later came forward and told the FBI and Sheriff’s Department that Xing had trafficked them. Federal prosecutors took over the case and arrested Xing again. The state charges were dropped, and a federal grand jury indicted Xing in September 2020 on the five trafficking charges.

Witness 1, the first accuser to testify at the trial, said Xing never told her sex would be part of her job at Sunshine Massage. Within the first couple days of work, a massage customer demanded sex.

“I was very scared, so I tried to rebel,” she testified.

The customer told her he’d already paid Xing for a sexual encounter, then climbed on top of Witness 1, covered her mouth and told her to keep quiet, she said. “He raped me,” she testified.

When she reported the assault to Xing, Witness 1 told jurors, she replied: “That’s how they all act here.”

He started making peppermint castile soap in his Pershing Square tenement in 1948. Here’s the very California story of the man, the cultish product and the progressive company.

The witness, who was married to an American and had a green card, said she kept the job for more than a year because she did not want her family to know about the sex work and feared what Xing might do with a copy of her photo ID.

She recalled Xing telling her: “Rest assured, I won’t let your husband find out about this.”

Xing sometimes used “threatening language,” she testified. Xing claimed she would pay “some Vietnamese people and some Mexicans, and they would do things for her,” she added. Xing said “she knows some people in gangs, and they can hurt me,” she said.

When Witness 1 refused a customer’s request for sex without a condom, Xing yelled at her, she told jurors.

It was left to the jury to reconcile the purported abusiveness with Witness 1’s investment with Xing in the Rosemead brothel where a security camera recorded her hugging a customer who got off on “the girlfriend experience.”

On the video, jurors saw Witness 1 opening a gift-wrapped box, taking out a scarf and thanking him, then leading him into a private room.

A bigger threat to the prosecution was the immigration clearance that the other four accusers got as a result of cooperating in the investigation of Xing.

The United States grants up to 5,000 “T” visas per year to victims of sex or labor trafficking if they can prove they are assisting in the prosecution of a trafficker. The visa authorizes them to live and work in the U.S. Family members are eligible too.

The FBI, the U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles and the Sheriff’s Department each helped secure T visas for these four Xing accusers and two of their children.

The visas were the thrust of Xing’s defense. This “golden ticket of immigration,” her attorneys argued, motivated the four masseuses to falsely allege Xing trafficked them.

“This is a case about lying witnesses,” Christerna told the jury.

Prosecutors dismissed the visas as an “irrelevant side show.” And the masseuses denied lying to get immigration papers.

But on the cellphones and iPads seized from Xing and two of the masseuses, there was almost nothing to buttress their allegations. Agents found ample evidence of commercial sex, but no confirmation that any of it was forced.

The closest thing they saw was Xing texting a masseuse that things would “not end well” if she kept turning tricks at home, which the defense argued was just a threat to fire her.

When Xing’s legal team mined the devices, they discovered a trove of exculpatory photos, videos, audio recordings and texts that cast doubt on her accusers’ credibility by showing them having a good time with Xing at social gatherings.

One of the four accusers told jurors that the first time she had to service “an old guy” at Xing’s condo, she felt compelled to provide sex because she couldn’t afford to give him a refund if he demanded one.

If she refused a customer, the masseuse said, Xing “would curse me.” “She was very mean.”

Mei Xing was a madam, there’s no disputing that. But she was not a trafficker.

— Mei Xing attorney Neha Christerna

Some of the sex customers at Sunshine Massage were police officers who were not required to pay, according to the masseuse.

In a letter outlining evidence for Xing’s attorneys, prosecutors claimed that one customer they identified only as “the Cop” would force masseuses to have sex against their will. The women were instructed to “do whatever the Cop wanted” and were led to believe he got sex for free because Xing was paying him for protection, prosecutors said in the letter, which was filed in court.

Testimony about encounters with this cop was direct evidence of Xing’s guilt, one of the many ways she trafficked victims “by force, fraud, or coercion,” Assistant U.S. Attys. Damaris Diaz and Scott Lara wrote.

The masseuse undercut that argument at the trial when Diaz asked how it felt to serve a cop who didn’t have to pay. “I felt that was somewhat safer for me,” she testified.

Another masseuse testified that she was raped twice during her brief stint at Sunshine Massage in December 2016, once at the massage parlor and once at Xing’s condo. The tall and strong man who assaulted her at the condo bruised her arm, she said, and left her bleeding between the legs. Afterward, she testified, Xing told her it was “not a big thing.”

At the end of her gig at Sunshine Massage, Xing shouted and told her not to return, shaming her in front of 15 or 16 co-workers and muttering that she could easily pay “to make someone disappear or perish,” the masseuse testified.

Other masseuses told jurors that they, too, heard Xing say she could “buy a life” for only $2,000 or $3,000, a comment she denied making.

When masseuses resisted Xing’s demands that they engage in sex acts against their will, Xing threatened to report them not just to police or immigration authorities, but also to criminals in the U.S. and China, the FBI charged in its initial criminal complaint against Xing. One of the masseuses testified that she heard Xing’s “younger brother in China is a gang member.”

Xing’s brother traveled from Tianjin to Los Angeles to testify on his sister’s behalf. He denied that either of them had connections to China’s criminal underworld. One of Xing’s attorneys asked that the brother’s name not be published, citing safety concerns.

The government suffered yet another setback when a masseuse testified that she never heard Xing make any frightening threats.

Confusion over whether the masseuse claimed in her T visa application that she was trafficked into the U.S. or trafficked while in the U.S. led to another remark that helped the defense.

“I absolutely did not say I was trafficked,” she testified. “I came on a tourist visa. Who trafficked me?”

Xing’s trial put on display the raw power of federal judges to shape the boundaries of what evidence can be put before a jury — and the impact that can have on the outcome of a trial.

U.S. District Judge Otis D. Wright II ruled repeatedly against Xing, most importantly when he rejected a defense request to let witnesses testify about her accusers’ history of prostitution.

Xing’s lawyers told Wright it was crucial to show the jury that all five accusers worked as prostitutes both before and after their alleged trafficking by Xing: At nightclubs in China; in Malaysia; at massage parlors in El Monte, Thousand Oaks and the Bay Area; in hotels and houses around Southern California.

None of them were “bamboozled, forced or coerced,” several were arrested on prostitution charges, and some brought their own sex customers to Xing, her attorneys told the judge.

“To conceal this evidence from the jury would deny Ms. Xing her right to fully confront the witnesses against her,” especially in the context of the T visas, they wrote in a court filing.

Those who’d been arrested had jeopardized their pending asylum applications, heightening their interest in casting themselves as trafficking victims who qualified for a T visa, according to the defense.

Steele said the judge should not allow the accusers, unchallenged, to simply tell jurors: “I had no idea. I went into this massage parlor without a license to work and I had no idea ... that sex was going to be going on in here.”

Testimony about past sexual behavior by a purported victim of sexual misconduct is generally not allowed at criminal trials under federal rules of evidence. But a judge can allow such testimony if its exclusion would violate the defendant’s constitutional rights.

Prosecutors said Xing’s attorneys were trying to “poison the jury” with the idea that the masseuses “may have previously consented to sex work, and therefore cannot be believed.” Prostitution work before or after the trafficking by Xing didn’t matter, Diaz told the judge.

“What matters is whether the defendant forced them or defrauded them or coerced them into committing commercial sex work for her benefit or at her direction,” she said.

Wright took the prosecution’s side.

“One of the things that we’re not going to do is start dragging people through the mud about their sex lives before and their sex lives after,” he said.

The death of troubled eye surgeon Mark Sawusch in his Malibu oceanfront house exposes how a Fresno hairstylist and Hollywood actor took over his home, dropped acid with him and drained his fortune.

Tensions between the judge and the defense escalated a couple weeks later when Steele raised concerns that jurors might have seen Xing’s ankle shackles under the defense table. On the brink of opening statements, Wright declared a mistrial over the shackles issue and recused himself from the case.

The parties regrouped to start again. U.S. District Judge Fernando M. Olguin took over the case, an abrupt switch from an appointee of Republican President George W. Bush to a judge put on the bench by Democratic President Obama.

Olguin, who presided over the trial, gave more leeway to the defense. He dismissed two of the five charges after hearing two of the masseuses’ testimony and finding the evidence too weak to put before the jury.

Olguin also let Xing tell the jury in the trial’s final hours what she knew about her accusers’ history of prostitution when she hired them.

They’d all been referred by fellow sex workers, Xing testified. She mentioned some of the paid sex gigs she believed had preceded their work at Sunshine Massage — at a hair salon in China, a house in Santa Barbara, the massage parlor in Thousand Oaks.

Prosecutors looked stricken as jurors absorbed the details.

One of the things that we’re not going to do is start dragging people through the mud about their sex lives before and their sex lives after.

— U.S. District Judge Otis D. Wright II

Deliberations lasted about five hours. The jurors, who were not publicly identified, agreed there was reasonable doubt about whether Xing had forced any of the women into sex against their will.

“The trafficking part of it just wasn’t there,” one juror said later. Another said the prosecution’s case “just didn’t make sense.”

The foreman handed the jury’s verdict sheet to a court clerk.

We, the jury, “unanimously find the defendant Mei Xing not guilty,” the clerk read out loud three times.

Tears rolled down Xing’s cheeks. She joined the palms of her hands in a gesture of gratitude and called out to the jury, “Thank you.”

Denied bail, Xing had been locked up for more than three years in a federal jail a few blocks from the courthouse. Olguin told her she would be released that afternoon.

Xing turned to Christerna and Steele and hugged them. “You saved my life,” she told them.

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.