Column: Enough with the lube jokes. The charges against Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs are no laughing matter

Everyone needs to stop talking about the lube. Right now.

The arrest of music mogul Sean “Diddy” Combs is not about the 1,000 bottles of baby oil and lube discovered during the March raids on his Los Angeles and Miami properties; it’s about allegations of coordinated and documented physical and sexual abuse.

It’s not about the slickly named “Freak Offs” parties; it’s about alleged systematic coercion, threats and trafficking of multiple women over many years.

It’s not even about Diddy, or at least not just Diddy; it’s about the hundreds of people who enabled him, the thousands who turned a blind eye and the culture that, once again, allowed the brutal treatment of women, and men, to remain an “open secret” for years as long as the perpetrator is rich, famous and powerful enough.

But sure, let’s make jokes about all that lube.

On Tuesday, a day after Combs’ arrest in New York City, federal prosecutors made public the 14-page indictment in which Combs is charged with sex trafficking, racketeering and transportation to engage in prostitution. Much of it focuses on Combs’ “Freak Offs,” to which, prosecutors say, Combs and his associates lured female victims with promises of a romantic relationship and/or career support, ensuring participation “by, among other things, obtaining and distributing narcotics to them, controlling their careers, leveraging his financial support and threatening to cut off the same, and using intimidation and violence.” (Combs pleaded not guilty to the charges and will remain in custody awaiting trial.)

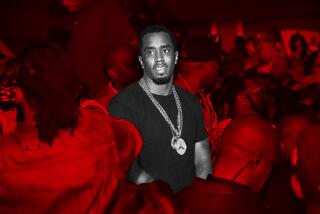

Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs was arrested in New York after a grand jury indictment. Combs is facing multiple lawsuits and is the subject of a sweeping sex trafficking probe.

The indictment paints the hip-hop superstar not only as a man with a pattern of abusive behavior toward women but also, with the racketeering charge, as the head of an organization that regularly carried out illegal acts.

In addition, it details evidence obtained during the course of the federal investigation that led to his arrest and arraignment, which included narcotics, AR-15 rifles and ammunition, devices containing videos of “Freak Offs” and more than 1,000 bottles of baby oil and lubricant.

Not surprisingly, the baby oil and lubricant, rather than the narcotics, the AR-15s or, you know, the alleged horrific crimes, immediately caught the public’s attention, particularly on social media, where “Johnson & Johnson” immediately began trending.

“Here I am keeping good company with [Drew Barrymore],” rapper 50 Cent posted on Tuesday, “and I don’t have 1,000 bottles of lube at the house.” Even the hosts of “The View “ noted the lube in their discussion of the indictment, with Whoopi Goldberg and Alyssa Farah Griffin laughing as they reminded audiences that the possession of lubricant is not a crime.

But as the show’s legal expert Sunny Hostin quickly pointed out, it could be evidence of one — and not just of the “Freak Offs,” which, as described in the indictment, involved Combs using “force, threats of force, and coercion to cause victims to engage in extended sex acts with male commercial sex workers,” distributing “a variety of controlled substances to victims, in part to keep the victims obedient and compliant” and recording sex acts without permission.

The fact that an overabundance of lubricant is more conspicuous than accounts by multiple women of Combs’ sexual and physical abuse only underlines the larger problem. Seven years after #MeToo, many women remain reluctant to speak out about abuse they have suffered at the hands of the rich and powerful, and those who do often find that the public, instead of being more sensitive, has become inured and indeed more skeptical, especially of those who do not have “receipts,” including video. And the inability to leave an abusive situation or relationship is still too often equated with consent.

Last year, four women, including Combs’ longtime girlfriend Casandra “Cassie” Ventura, filed lawsuits in which they accused Combs of sexually and physically abusing them; producer Rodney “Lil Rod” Jones also filed a similar suit. Combs denied all allegations, suggesting that the plaintiffs were looking for a payday — he and Ventura settled out of court — until earlier this year, when CNN published a 2016 video of him violently assaulting Ventura in a hotel corridor. Combs then apologized, claiming he had gone into therapy and rehab.

Following Combs’ arrest, social and legacy media were full of people talking about how his alleged behavior was an “open secret” — and as the cases of Harvey Weinstein, Jeffrey Epstein and other #MeToo predators showed, far too often, “open secret” is code for “if you’re rich and powerful enough, you can get away with anything.”

But reading the Combs indictment, and then watching as people began cataloging all the “red flags” that had been raised about Combs for years, it was difficult not to think of Gisèle Pélicot. For weeks, the world has watched in horror and admiration as Pélicot sits through the trial of her now-ex-husband, Dominique, who on Tuesday confessed to drugging and raping her for years, and dozens of men who are charged with raping her at his invitation.

How, we wonder, could so many men, outwardly so ordinary, allegedly commit such a crime? How could others who may have seen but did not respond to Dominique Pélicot’s chat-room invitation stay silent? Why did no one call the police?

Like the alleged crimes in the Pélicot case, the charges against Combs are for events that prosecutors say spanned decades and allegedly involved many people, including those in Combs’ employ — hence the racketeering charges. Combs is also alleged to have weaponized nondisclosure agreements (another familiar element of #MeToo cases), but did no one involved in the considerable effort it took to arrange the “Freak Offs” described in the indictment consider breaking their silence or making an anonymous call to the police?

As a Times report detailed earlier this year, Combs has long packaged himself as an outlaw made good — his keystone company is called Bad Boy Entertainment, after all. An iconic figure who helped make hip-hop a cultural force, he is a rich and powerful man who, until the recent pileup of sexual assault suits, was consistently able to shake off trouble.

As with Weinstein, his success (and aggressiveness) outweighed the rumors; as with Epstein, there is speculation about whether Combs will name other participants in the alleged “Freak Offs” and if those names will offer him any leverage while fighting the new charges.

Just as Weinstein, Epstein and many others have proved, our culture often has a difficult time accepting the fact that people who are funny or generous or capable of creating great art can also be monsters of epic proportions. And pretending that such contradictions don’t exist, all historical evidence to the contrary, makes the rest of us a bit monstrous too.

It’s natural to joke about 1,000 containers of lubricant — that is a hell of a lot of lube — but it shouldn’t be a substitute for or a distraction from what the charges actually allege: That a rich and powerful man used his business and many of his employees to systematically drug, assault, brutalize, threaten, kidnap and exploit people for years and call it a “party.” There’s nothing funny about that.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.