A man lies flat on his stomach on the floor of an apartment high above the La Brea Tar Pits.

He isn’t moving. His hands are tied behind his back. His face rests in a pool of blood spilling from his neck.

A glass candleholder is shattered on the ground nearby and a chair is knocked over, signs of a struggle in the otherwise neat apartment.

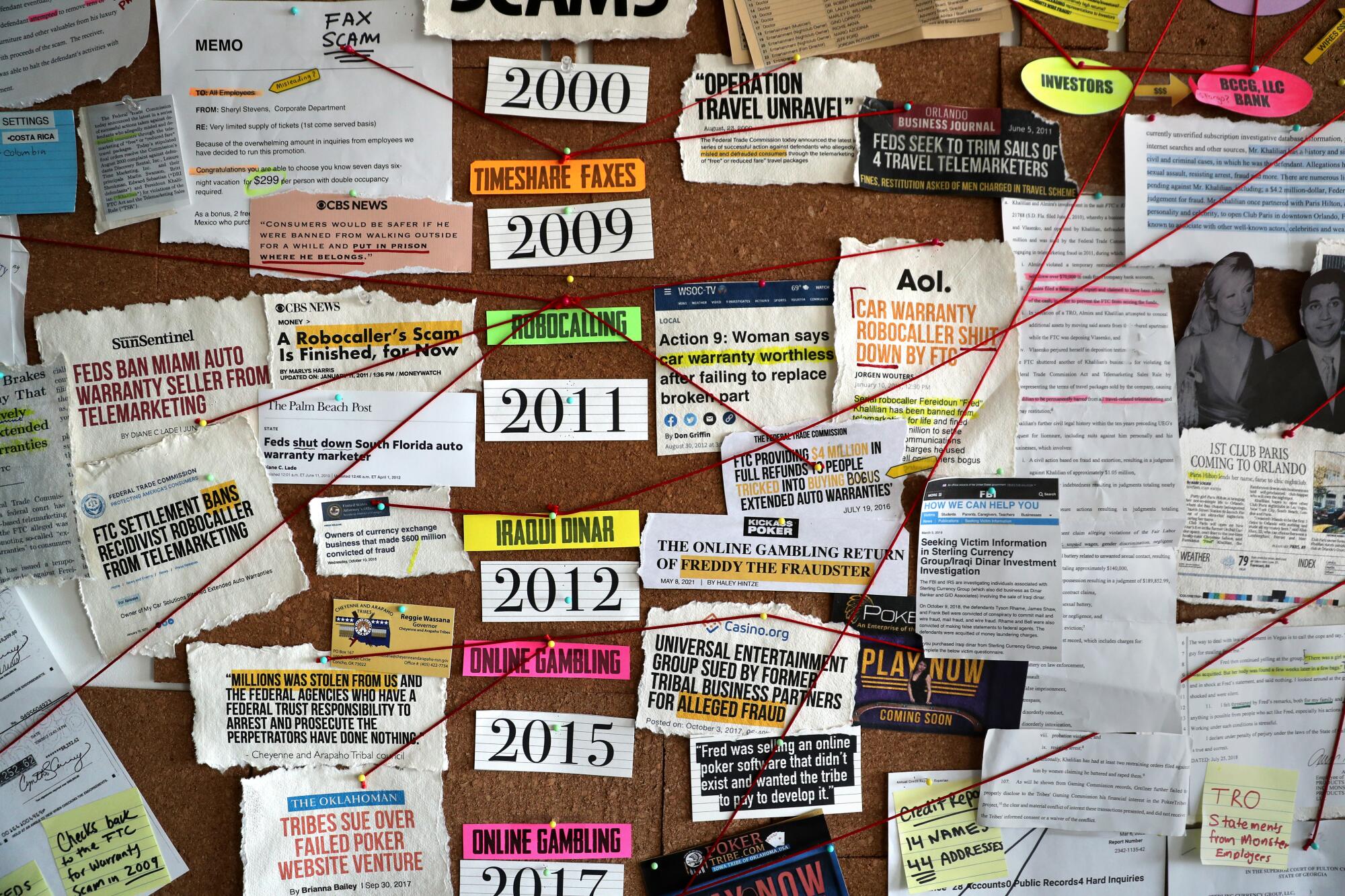

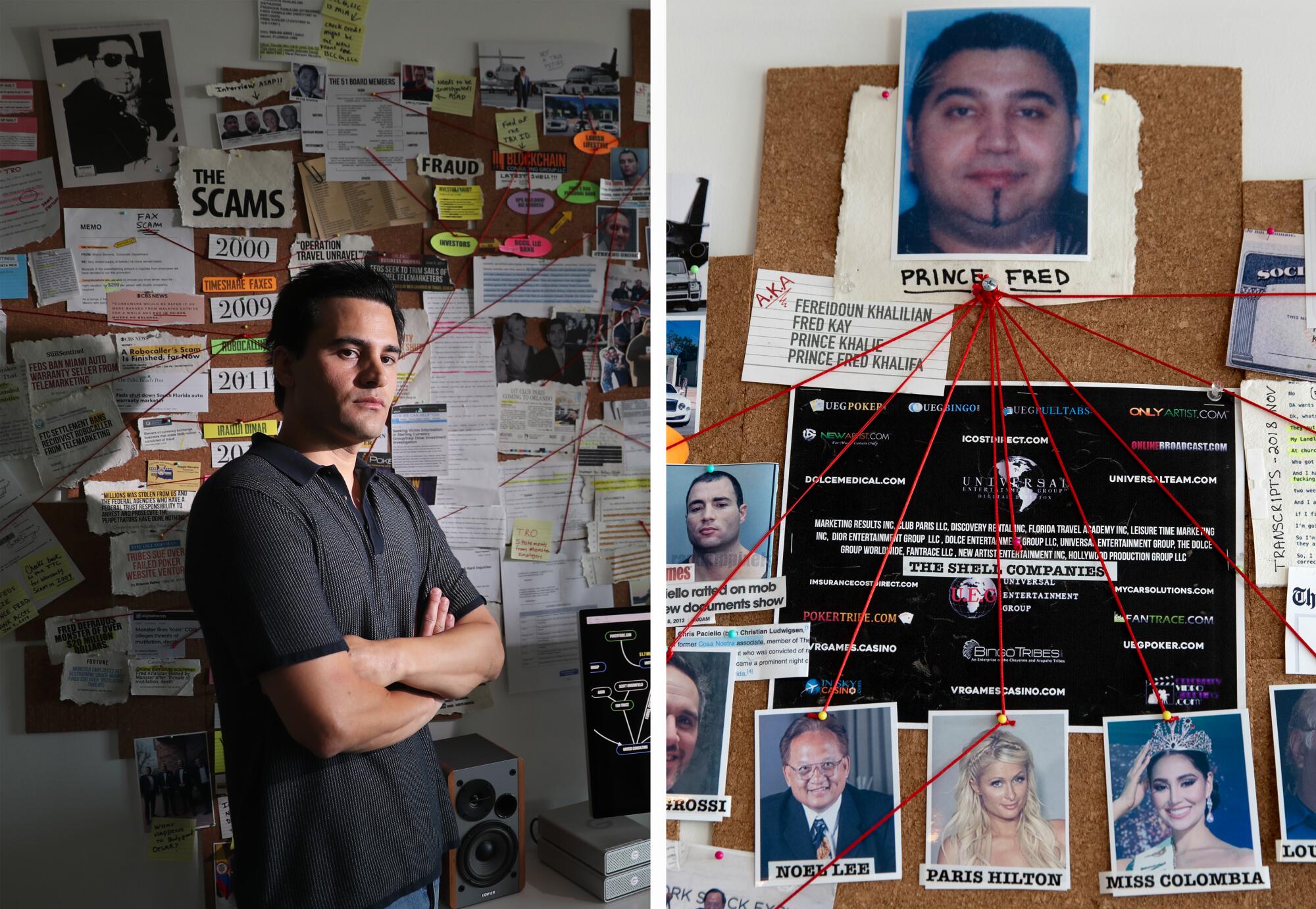

On the wall is a corkboard dotted with cutouts of articles, court papers and photographs. Red string leads between related incidents along with photos and names and dates. All the string ties back to a photo at the top of a man: “Prince Fred.”

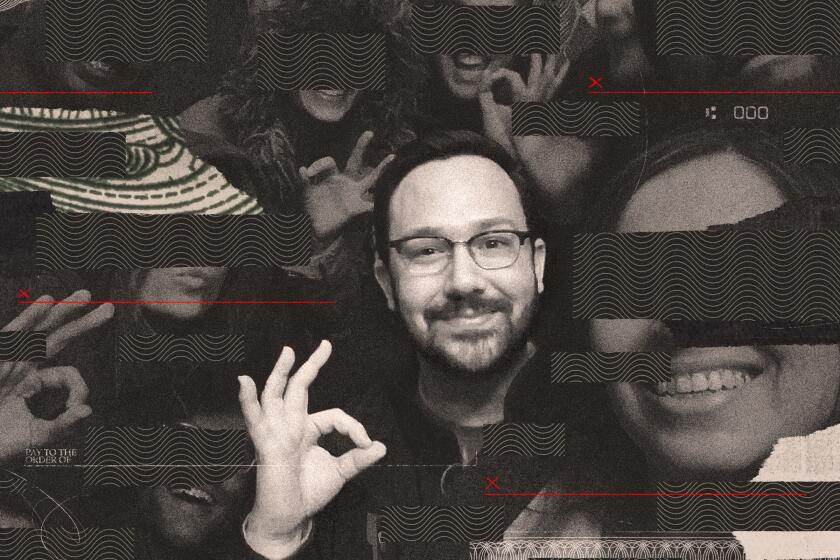

It could be a scene out of a movie. Someday, it probably will be. The man on the floor is a documentary filmmaker. What started as an exposé of a wealthy businessman with a checkered past had morphed into a low-budget, high-stakes, life-or-death drama.

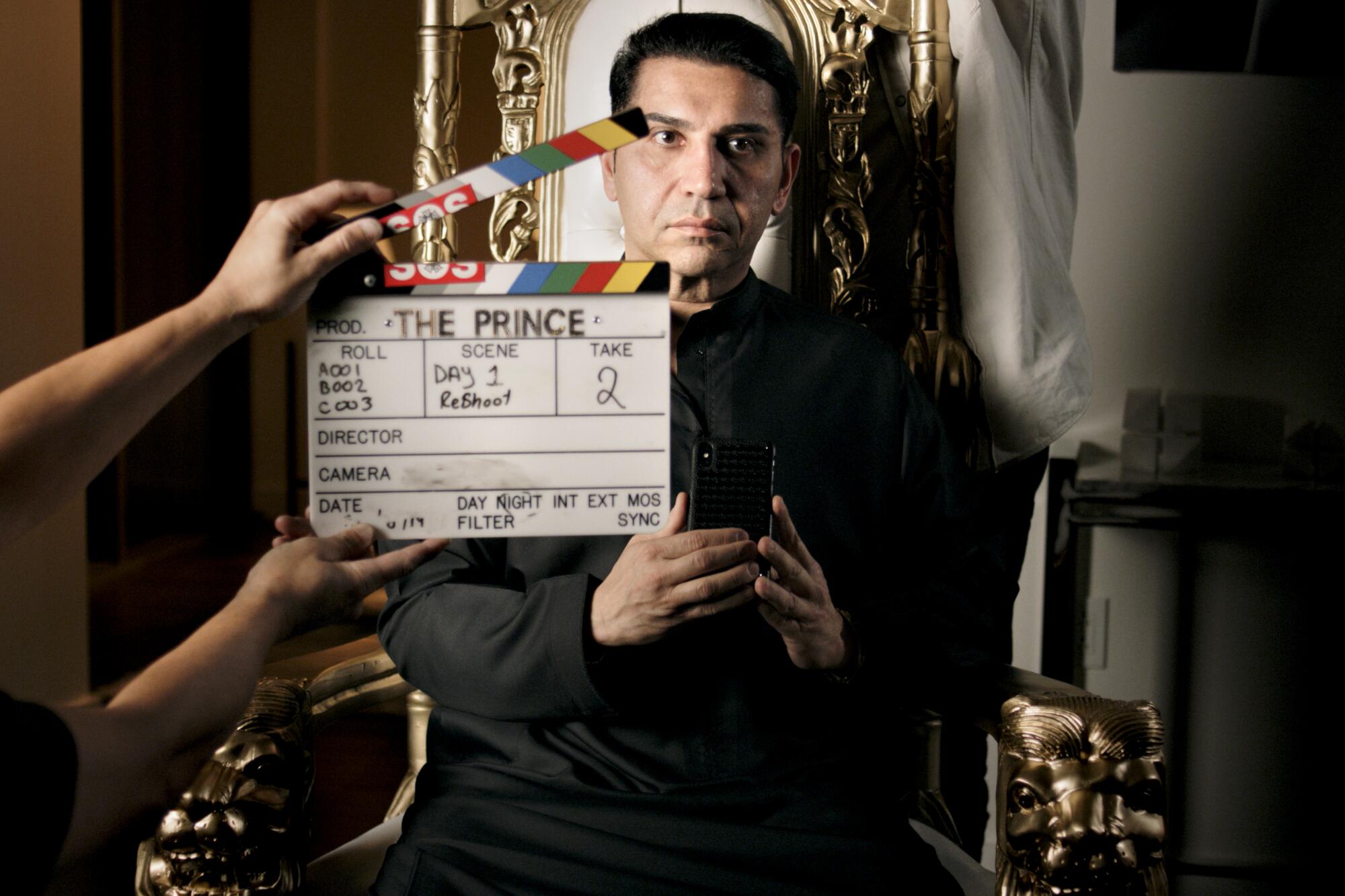

J. Esco was working as a computer technician in Florida when Fereidoun “Prince Fred” Khalilian hired him for a repair job in 2009. He was soon working full time for Khalilian: a job offer at three times his salary was hard to refuse, Esco said.

Khalilian’s lavish lifestyle impressed Esco. His boss ran in celebrity circles; he had helped open Paris Hilton’s short-lived nightclub in Orlando, Fla. He drove a Range Rover and claimed to have a Bugatti and a Lamborghini at his house, according to prosecutors in a criminal complaint. He wore expensive jewelry and had a security team of at least four bodyguards who accompanied him when he went out, often spending tens of thousands of dollars in a single night at a club, the complaint said.

For a year, Esco ran IT for Khalilian’s robocall company while helping his boss launch a social media music company. That came to an abrupt end when federal agents raided Khalilian’s office in 2010.

“I hear a huge bang and I hear someone say, ‘Don’t f—ing touch your computers, don’t touch your mouse,’ ” Esco recalled, saying agents pointed guns at him as he led them to the company’s servers.

The raid resulted in a 2010 Federal Trade Commission lawsuit alleging that Khalilian misrepresented car warranties to unsuspecting customers. Khalilian and his company were ordered to pay a $4.2-million judgment in the case.

After the raid, the company shut down and Esco was out of work.

Esco said his former boss promised to help him get back on his feet. “In my mind I was like, ‘F— this, I’ll never talk to this guy again.’”

A few years later, Esco moved to Los Angeles to try his hand in the entertainment industry. He splurged on a high-end cinema camera and shot commercials and short films for free to build his portfolio.

Work was satisfying but hard to come by.

He produced dozens of commercials as well as some short films and a feature film, “Catalyst.” He also began working in documentaries. He was cobbling together a living in Hollywood as a cinematographer and producer, but he was always on the lookout for the big project that might catapult him into more marquee work.

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Esco was shooting an interview with boxing trainer Freddie Roach at hairstylist Giuseppe Franco’s Beverly Hills studio in 2019 when Khalilian coincidentally arrived on set.

They kept the cameras rolling as Franco introduced his acquaintance Khalilian as a billionaire from Dubai. Khalilian said he was soon to be the next chief executive of Samsung, according to Esco.

“In my head I’m like, ‘Oh, he’s the biggest bulls—er in the world,’ ” Esco said.

After they cut, Khalilian recognized his former employee and the two reconnected, according to Esco.

As they spoke, Esco had an idea. He could make a documentary about his onetime boss — a high-rolling socialite with a shadowy background.

Esco said he went home and Googled Khalilian and found articles about scandals involving the businessman spanning nearly two decades, with allegations including battery, extortion and “threats of mutilation, death and threats to family.”

A partial list of legal claims involving Fereidoun Khalilian

In 2000, the Federal Trade Commission sued Khalilian for a telemarketing scheme in which he made deceptive pitches for travel packages, the FTC said. Khalilian argued in court papers that he had not committed any illegal conduct. He was ordered to pay $185,000 in a settlement in that case.

In 2006, Khalilian was charged with battery on a law enforcement officer. He pleaded no contest to a lower charge of disorderly intoxication, according to Florida court records.

In 2007, Khalilian was accused of battery and false imprisonment by a former employee, according to the Orlando Sentinel. He pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor battery charge in in the case, according to court records. His attorney argued that the charges were not strong and had a taxi driver and security guard testify that the victim “appeared happy and content after leaving Khalilian,” according to the Sentinel.

In 2014, Khalilian was sued by a former business partner, Stefano Grossi, for allegedly misappropriating $1.7 million of Grossi’s investments in their company, according to a lawsuit filed in Georgia. Khalilian also made a deal with a Native American tribe for poker software for $9.4 million and excluded Grossi from the money, according to the complaint. After a jury trial, Khalilian was ordered to pay $4.7 million to Grossi in 2019. Khalilian’s lawyer at the time said he intended to appeal “based on certain evidence that was excluded at trial.”

In 2018, Khalilian was “exited” from his role at the audio company Monster after staff accused him of making “threats of mutilation, death, and threats to family,” according to a Monster news release. A temporary restraining order was filed against Khalilian at the time by Monster. Khalilian claimed in a suit against Monster that the company’s other executives made false accusations against him in order to “humiliate” him, the suit said. The case against Monster was dismissed by a federal judge.

“He’s ... done a lot of stupid things and gotten himself in a lot of legal trouble,” said David Lilenfeld, an attorney who’s sued Khalilian twice. “He knows how to separate people from their money.”

Khalilian has defended himself in court, arguing that allegations made against him in lawsuits and criminal cases were false. He has been ordered to pay settlements in some cases and pleaded no contest to lesser charges in criminal proceedings.

Esco thought the documentary could be his big break, but only if he could get Khalilian to participate. He came up with an unorthodox solution in the practice of documentary film: He would lie to his subject. To gain Khalilian’s trust, Esco promised the film would cast him in a favorable light.

“I’m actually conning the con man to come into this documentary,” Esco said.

The documentary got off the ground quickly, as Esco interviewed former business partners, bodyguards and even an ex-fiancee of Khalilian who he felt corroborated his view of Khalilian.

Khalilian explained his extravagant wealth by telling people he was an Arab prince — though his national origin changed depending on whom he was talking to, prosecutors and family said.

It wasn’t until about a decade ago that he began referring to himself as “Prince Fred,” Khalilian’s first cousin Paradis Khalilian told The Times.

Hollywood producer David Brown and his companies have been sued at least 10 times and ordered by judges to repay about $5 million to investors.

“Everyone was calling him ‘Prince, Prince, Prince,’ ” she said. “I asked him what’s the story and he started laughing about it. ... He was like, ‘I basically am a prince. I’m richer than every prince.’

“He has no royalty background,” she said.

His background is Persian, not Arabic, said his cousin. He was born in Iran and moved to Turkey when he was 12, then Germany when he was 13 and eventually the United States when he turned 18, she said.

Esco spent four days interviewing Khalilian, gathering his subject’s version of his life story. Khalilian seemed more interested in a Kardashian-style reality show than a documentary, Esco said.

“He wanted me to ask him as he got out of the car at the club, ‘How’d you lose so much weight?’ ” Esco said.

Esco felt the documentary was taking shape. But the ruse could go on only so long.

A source whom Esco approached about an interview tipped off Khalilian, Esco said. Now he knew the real direction of the film — and he wasn’t happy about it.

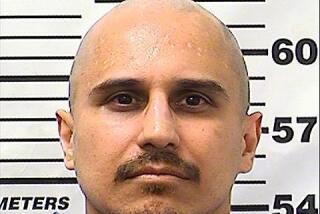

Mike Sherwood pulled up outside Esco’s apartment in March 2022. He worked as the head of Khalilian’s security team, and for the last month his boss had been complaining to him about Esco’s documentary, saying it would ruin his life, according to the criminal complaint. Sherwood told his boss he would talk to Esco about the documentary, the complaint said.

Sherwood said he had no plans to resort to violence when he traveled to Los Angeles to speak with Esco — he hoped to talk the filmmaker out of making the documentary.

The two met on Esco’s roof.

Esco showed Sherwood parts of the documentary about Khalilian and asked if the bodyguard would be open to an interview for the project, Esco said.

Sherwood agreed and was filmed in June 2022, though he continued to work for Khalilian. He said he spoke of the “positive and negative” sides of Khalilian in his interview and informed his employer that he had talked with Esco.

“I was very honest about his personality being up and down. But at that point I didn’t think he was a horrible person,” Sherwood said.

For a time, Khalilian appeared less bothered by Esco, Sherwood said. Then Esco began making calls to his former boss.

He started to goad Khalilian, calling from spoofed numbers and saying nothing other than “habibi” — an affectionate address in Arabic — or “Fred,” and hoping that Khalilian would lose his temper, prosecutors said. Esco would record the calls. He called Khalilian about 20 times in early March 2023, according to prosecutors.

Esco said he hoped Khalilian might make threats that he could record and use in the documentary. And Khalilian did, according to the criminal complaint and audio recordings reviewed by The Times.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

“When I’m done with you, I’m going to cut each one of your f—ing fingers off,” Khalilian said on one recorded call on March 8, according to a transcript in the complaint. “I’m going to f— you up, b—. I’m going to have your f—ing head.”

Initially, Sherwood said, he did not take his boss’ tirades seriously.

“Fred would lose his mind from time to time,” Sherwood said.

But eventually, Sherwood said, he realized these threats were real. In March, Khalilian solicited Sherwood to have Esco killed for $20,000, a federal agent wrote in the criminal complaint.

The two messaged about Esco’s home address and about how to get Esco outside. One idea they floated was to lure him out with an invitation from a “celebrity chef,” according to the criminal complaint. Sherwood texted about hiring “Mexicans” for some job, paying them $1,000 each, according to the criminal complaint.

On March 16, Khalilian messaged Sherwood, according to prosecutors.

“I need this done.”

“Already booked. Not leavin ya hanging. I got it,” Sherwood texted Khalilian, according to the complaint. “I’ll be there personally.”

When Esco woke up on March 17, he saw he had missed a text from Sherwood: “Call me when you can.”

When Esco called back, Sherwood said, he filled him in on the whole arrangement.

Esco’s mind went numb, he said. He knew that Khalilian hated him, but he hadn’t thought his former boss would resort to violence.

Esco was on edge, even though Sherwood insisted he was in no real danger. (“Bro, I’m obviously not going to do it,” Sherwood recalled telling the filmmaker.)

Khalilian wanted proof of the murder by the next day, Sherwood told Esco.

The two hatched a plan so crazy it just might work: a faked murder, more high school film project than Hollywood motion picture.

Esco’s girlfriend would take a photo of the crime scene. Then they would send the photo to Sherwood, who would turn it over to Khalilian as proof Esco was dead.

There was no time for a Hollywood makeup artist, as Esco wanted, so after the phone call, he went straight to Party City and purchased fake blood.

Esco choreographed the scene in his head. If someone were to murder him, how might it go down? He toppled a living room chair and shattered a glass candleholder on the ground. He imagined the killer might have used the candleholder to knock him out before slitting his throat with a knife, Esco said. He tied his hands up with an extension cord and lay still on the ground.

His girlfriend took dozens of photos and videos and Esco sent them to Sherwood, he said.

Sherwood passed along one of the images of the staged killing to Khalilian, according to prosecutors. He told Khalilian that he had hired a group of Mexicans to carry out the murder and that they buried Esco in a warehouse in Los Angeles, according to Sherwood and prosecutors. Within a minute, Khalilian sent $3,000 to Sherwood on Cash App from the account @$PrinceFredKhalilian, prosecutors said.

“For my guys,” he wrote as a note, according to the complaint.

Less than six hours later, Khalilian sent an additional $3,500, prosecutors said.

All in all, Khalilian paid Sherwood a total of $12,500 for the faked killing, according to the criminal complaint.

At this point in the murder-for-hire double cross, Esco and Sherwood still had not contacted law enforcement. Sherwood wanted to wait longer to go, he said. He believed Esco was in no real danger because Khalilian thought he was dead — and Sherwood hoped to continue collecting the payment for the killing, he said. Why not profit off the situation? he thought.

Instead, Esco went to The Times with his story after reading about another murder-for-hire plot in the paper.

Arthur Aslanian was a successful developer in the Valley. He is now accused of ordering a hit on two people to whom he owed money.

“I recently got a hit on my head and the hit man reached out to me yesterday, we worked together to fake my death,” he wrote in an email on March 19, two days after they faked the murder.

Esco then went to the FBI and told agents his story. The agents were interested. But before making an arrest, they wanted Khalilian to admit he had ordered a killing, Sherwood said.

Esco spent months living in fear. The man he believed wanted him dead was still walking free and taking international trips. What if he visited L.A.? What if they crossed paths?

The FBI told him to stay off the grid, Esco said. He could not post on social media, let alone go out for a meal. Every few weeks he’d sneak to the grocery store and back. He left the country for a bit, with the FBI’s permission, he said.

“I felt horrible. I was ordering in every day. It took a toll on me. You feel like you’re a ghost,” he said.

He worried that the FBI would not even arrest Khalilian. Maybe there wasn’t enough evidence to make a case, he thought.

Meanwhile, the FBI was keeping Sherwood busy. Sherwood recorded calls between himself and Khalilian and sent evidence of the cash payments from his phone, according to the complaint. He had to screen-shot all of his communications with Khalilian and share them with agents, Sherwood said.

On March 23, six days after the faked killing, Khalilian and Sherwood got on the phone.

“His body, nobody is going to be able to find him, huh?” Khalilian said, according to a transcript from prosecutors.

“No, no one’s going to be able to find him,” Sherwood responded.

“All right, cool,” Khalilian said.

“They actually asked if you wanted a souvenir,” Sherwood said.

“Yes. No, no, I don’t,” Khalilian said.

Sherwood laughed.

“I told them I’d ask, but that’s about it,” Sherwood said.

“Yeah, they like to cut heads and fingers and s—,” Khalilian said.

The FBI called Sherwood every day, he said. Khalilian said some stuff on their phone calls, but not enough, Sherwood said.

Finally, on June 20, the FBI told Sherwood to get ready for the final act.

Sherwood opened the door of his Porsche Macan on June 21 and prepared to put on the most important performance of his life.

Khalilian got into the car and the two men went for a drive around Las Vegas. The car was clean. Just a water bottle in the cup holder and a Dodgers hat on the dashboard. Federal agents had slipped a camera into the Dodgers hat, feeding sound and video directly to law enforcement, Sherwood said.

Sherwood got straight to the point, he said.

He showed Khalilian the belongings of Esco the FBI had given him — Esco’s passport, IDs, his Global Entry pass.

The belongings were further evidence, along with the staged photo, for Khalilian that the deed had been done.

As they sat in the car, Khalilian opened up, Sherwood said.

“If I didn’t pay you to do it, I was going to kill him myself,” Khalilian said, according to Sherwood.

The FBI would not share its recording of the conversation, but it did not dispute Sherwood’s retelling.

The two pulled into the parking lot of a Dunkin’ and suddenly were surrounded by law enforcement. FBI agents handcuffed Sherwood and Khalilian and tossed them into the back of a car, Sherwood said.

“I was like, ‘They must have found [Esco].’ He was like, ‘They didn’t find [Esco],’ ” Sherwood recalled.

Agents separated the two quickly, Sherwood recalled. They drove Sherwood back to the Porsche Macan and let him out. He was free to go.

“My hands still f—king hurt from the handcuffs,” Sherwood said, laughing.

But Sherwood knew he’d gotten what agents needed.

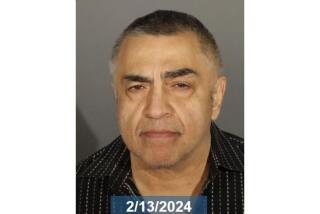

Fereidoun Khalilian is arrested in Las Vegas on suspicion of trying to have an L.A.-based filmmaker who was making a negative documentary about him killed.

Agents arrested Khalilian and prosecutors charged him with murder for hire for the plot to kill Esco and the payments he made to Sherwood. A federal magistrate judge in Nevada ordered Khalilian held without bond on June 26. He faces up to 10 years in prison.

“Mr. Khalilian maintains his innocence and looks forward to defending himself in court,” said his attorneys, David Chesnoff and Richard Schonfeld. “The actions of the government witnesses surely need to be examined; however, it would be inappropriate to make any further comment at this time.”

His attorneys argued in court that Khalilian should be released pretrial.

“While counsel understands that the charges are serious and that the government will assert that it has evidence in support of the charges, all remaining factors weigh strongly in favor of Mr. Khalilian being released,” Chesnoff wrote.

His attorneys also said Khalilian has no felony criminal history and has “tremendous family support.”

Esco said he wasn’t thinking about his documentary when he and Sherwood faked the murder. Nor, he said, did he consider it when he delayed reporting the situation to the FBI.

But the film is on his mind again now.

As news of Khalilian’s arrest made its way through Hollywood circles, production companies and financiers who had passed on the “Prince Fred” project reached back out to Esco and his partners.

“We had a really, really captivating character in Prince Fred. We had good interviews. But it didn’t have that extra, extra thing,” said Donovan Leitch Jr., Esco’s producing partner. “The murder for hire was the hook that was the one thing that sets this apart from all the other documentaries.”

Esco knows his approach to filmmaking put his life in jeopardy, but, he said, “Obviously, for the documentary, it’s a really good thing.

“I wanted to be behind the scenes for everything,” Esco said, “but it’s like this was destined.”

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.