Through a camera, darkly, L.A. artist Juan Escobedo searches for his Mexican roots

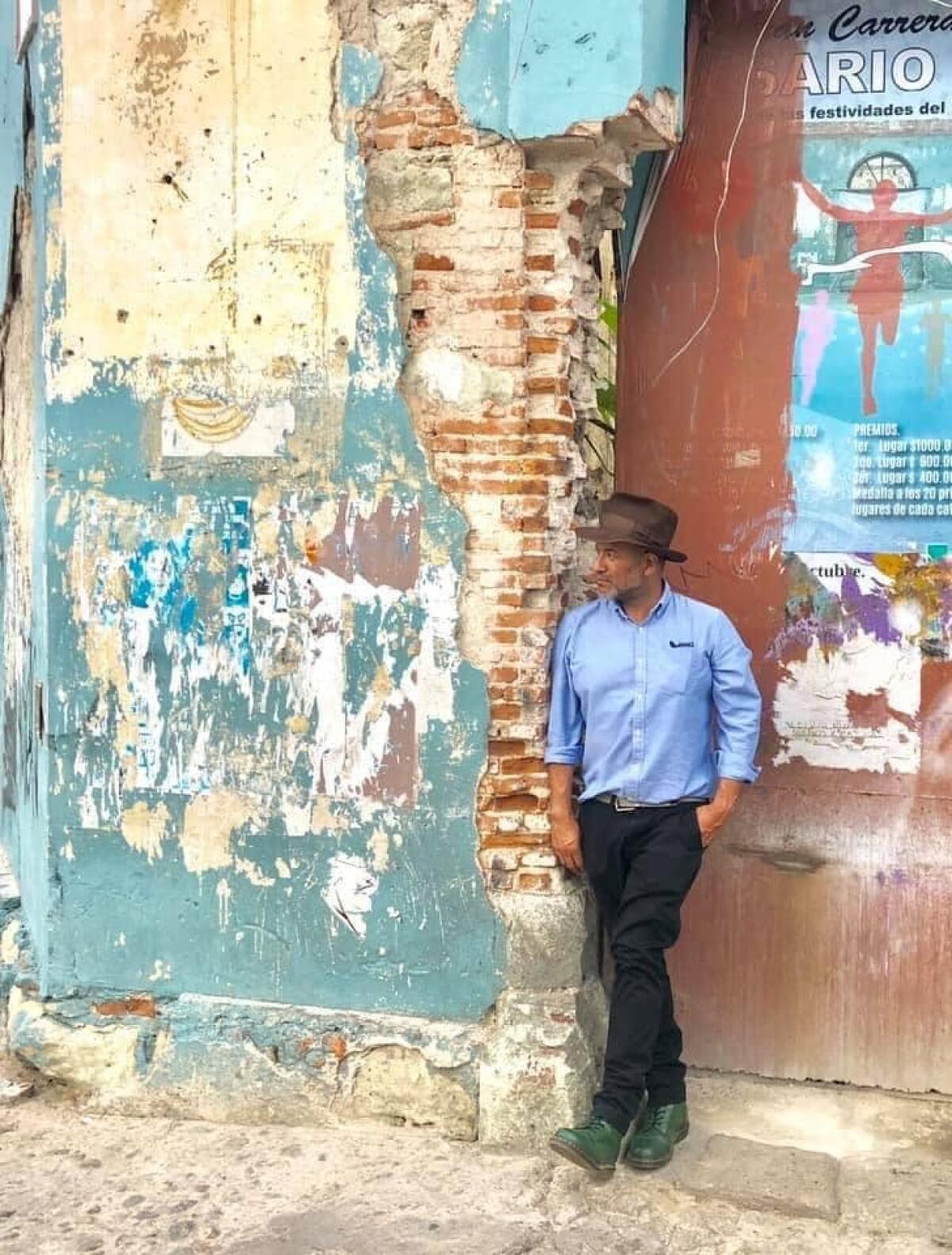

Juan Escobedo is one of those characters that you have to know to understand the rhythm of this city. Sociable and cultured, wearing his trademark hat, he keeps one foot in Los Angeles and the other on the south side of the border. His heart is divided between those two loves.

He was born in San Diego, but has strong roots in the state of Jalisco, where, by the way, his fondness for hats comes from. His passion for hats helped make him famous here, after the Los Angeles County Department of Arts and Culture selected his “El Sombrero de Miguel López” for a group show that was exhibited in downtown L.A.’s Gloria Molina Grand Park from March 11 to 18.

The photo was taken in 2018 and is a self-portrait of Escobedo wearing the sombrero of his grandfather, Miguel López.

“He was from Jalisco and he came to the United States when visitors paid 50 cents to cross the border,” Escobedo says. “He did not find out that he was part of the Bracero Program until years later.”

“My grandfather always wore a hat when riding a horse or doing farm work. The hat was an extension of who he was and the land he cared for. I’m honored to have been selected out of so many great artists to show my work in this exhibition. It’s like bringing it to life on the streets of this city.”

Escobedo knows very well that his home is here in California, but he also listens to the voices of his ancestors who constantly beckon him to experience the traditions, flavors and daily life of the towns of Mexico.

That is why he feels as much at home in a market in Boyle Heights, talking to young people who want to be filmmakers, as he does outside a church in Oaxaca, or in a town in Jalisco, enjoying the people, feeling sheltered, but at the same time a foreigner.

“How many of us have not felt that sensation upon returning to the land of origin?” asks Escobedo with a smile.

Escobedo’s penchant for shadows and angles comes from afar, specifically from Huejuquilla, Jalisco, where he was raised by his grandparents.

“Between dogs, cats, chickens and pigs, the house was kept in permanent semi-darkness,” he recalls. “The candles illuminated the images of the Virgin that my grandmother had, and the hats were part of the furniture in the house.... In Huejuquilla, in Los Altos de Jalisco, there was no electricity, only oil lamps, and I remember that there were always hats, virgins and the outstanding image of San Martín de Porres, the saint of animals.”

In that chiaroscuro environment, reminiscent of the landscapes and photographs of the Mexican writer Juan Rulfo, Escobedo developed his sensitivity toward images, and the need to find his roots.

From those childhood memories comes his need to experiment with shadows, lighting and silhouettes. And the best way to express that need was through photography, which he began to practice at 15 years old when he studied at La Jolla High School.

Through practice, he came to understood that the camera was not only a tool, but also a vehicle to raise awareness about different social issues. Thus was born “Trash and Tears,” the series of photographs that Escobedo began in 2017 in which he depicted actors and models in the midst of marginalized urban landscapes.

In this series Escobedo explores the problems of the accumulation of objects, mental health, poverty, graffiti and drug addiction through imagery of the garbage-strewn areas where unhoused people often are obliged to make their homes. “Trash and Tears” is a reflection on the ambiguous and precarious value of objects.

“What for some is garbage, for others is a treasure,” says Escobedo.

Although he feels he belongs to Los Angeles, where he arrived in 1991 to study theater with an emphasis in directing and photography at Cal State L.A and East L.A College, Escobedo has dedicated a good part of his career as a photographer to recovering his Mexican identity, both in Jalisco and in Oaxaca, where he has taken photographs that have earned him great personal satisfaction.

Although his foray into photography dates back to his student days, he found his other vocation by chance.

In 2007, a friend asked him to recite a poem entitled “I am a soldier in Iraq,” in which he narrates how veterans are treated once they return to the United States, where too often too many of them are forgotten and even despised by the rest of society.

After reading the poem, he illustrated it with images and sent the video to the Cannes Film Festival, where it won the award for best short film under four minutes from the Swiss Department of Arts and Culture. It also earned the Cinema of Conscience Award from the Sonoma Film Festival in 2008.

“When I got back to Los Angeles, I thought we should have a festival like this in East Los Angeles,” says Escobedo.

So he got to work. With the support of former L.A. County Supervisor Gloria Molina and Guadalupe Bojórquez of the Casa Cultural, he organized the East LA Film Festival, which has been taking place since 2008, and where the works of numerous local artists who are trying to stand out in this competitive industry come together.

Hand in hand with the festival, the East LA Society of Film and Arts, better known as TELASOFA, was born, a non-profit organization whose objective is to offer young people from marginalized areas of Los Angeles the opportunity to learn the art of cinema.

As a filmmaker Escobedo has built a reputation for himself. He was nominated for the prestigious Premio Imagen (2009), which recognizes positive portrayals of Latinos in film and television. His other works as a director include “Ruby,” a movie for Current TV.

In 2018, “Marisol,” a short film addressing the horrors of domestic violence and child abuse, won best dramatic short film at the Hollywood Reel Independent Film Festival and best actress awards for both lead actresses, Siennah Ortiz and Toni Torres, at the Women’s Independent Film Festival and at the Playhouse West Film Festival. In May 2022 this short film won best director, best child actress and best short film at the San Diego Movie Awards in Balboa Park.

The script for “Marisol” also became part of the permanent collection of the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, where it is available to researchers.

But Escobedo has a long way to go. Among his future projects is a film that addresses the issue of the Black population of Mexico. “It is a part of society that has been forgotten, marginalized and for centuries, tried to erase,” says Escobedo, who will soon travel to the states of Oaxaca and Guerrero to recover that part of Mexico’s history.

“If we forget who we are, we are lost,” he says.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.