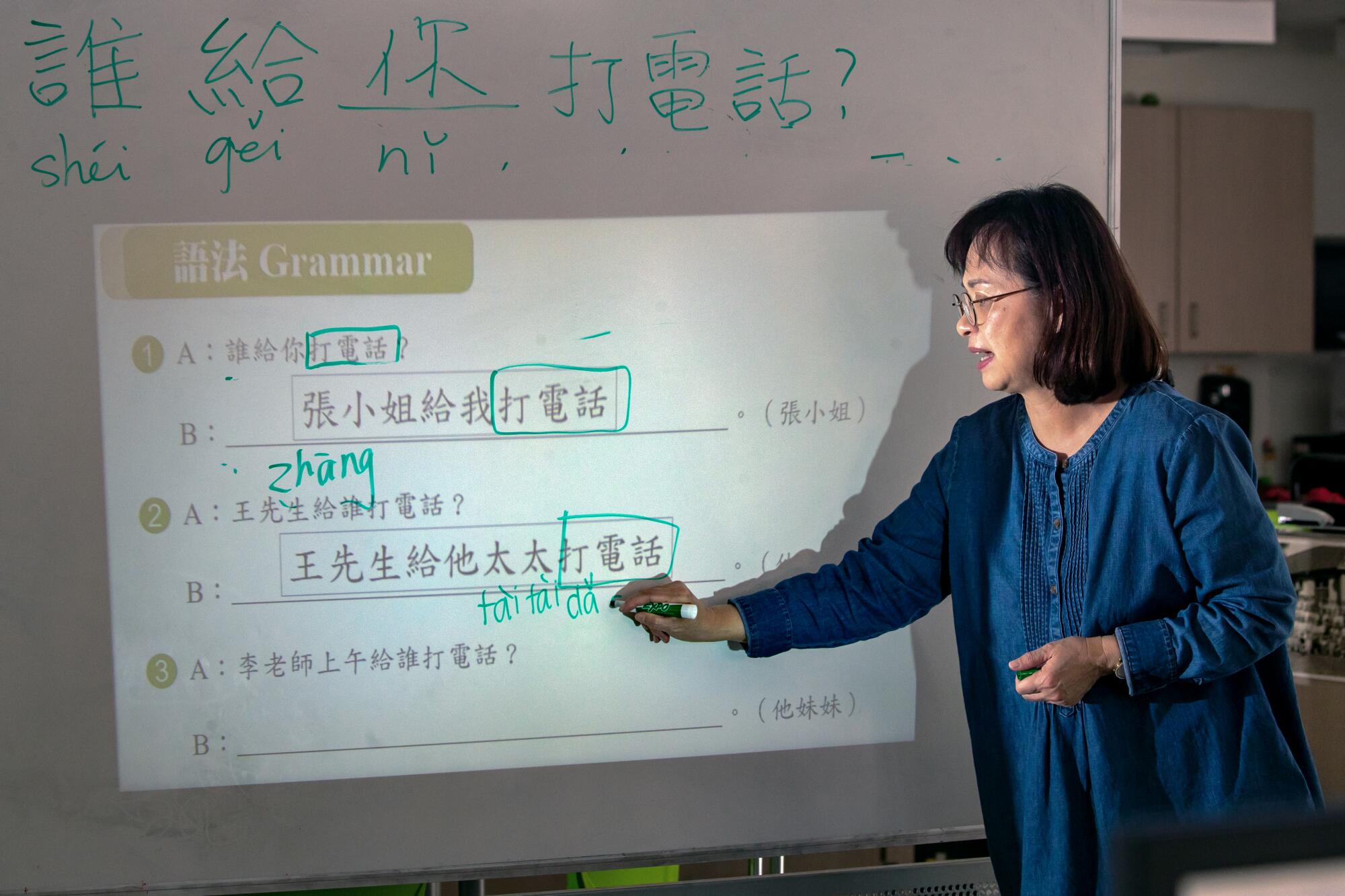

In the relaxed cadences of her native Taiwan, Kelly Chuang instructed her students to repeat after her.

“Wo bu shi taiwan ren. Wo shi meiguo ren” — “I’m not Taiwanese. I’m American.”

She projected the written Chinese for the phrases onto a whiteboard. “Taiwan” appeared in the traditional form, with 25 strokes in the second character alone.

The four adults were studying Mandarin, Taiwanese style — elaborately written characters over the simplified versions used in China, no “ers” appended to words, less of a curled tongue for “sh” sounds.

In a small way, as they struggled over the language’s four tones and learned how to make Taiwanese spring rolls last month in a classroom in San Marino, they were part of a high-stakes global chess game.

“It looks intense,” said Deseree Oaxaca, 25, as she stared at the characters for “Taiwan” on the board.

The class and others like it in the U.S. and Europe are backed by the Taiwanese government, which hopes to spread its version of Mandarin — along with its values of freedom and democracy — as China’s threats against Taiwan become increasingly bellicose.

China considers the island of 23.5 million people to be part of its territory and has promised to take it by force if necessary.

As relations between the U.S. and China worsen, Taiwan sees an opening to boost its soft power by pulling adults into classes with discounted fees, where they learn about Taiwanese popcorn chicken and Taiwan’s tallest building, in addition to grammar, writing and holiday customs.

Indigenous Taiwanese want to abandon their Chinese names, giving rise to a politically charged debate amid rising cross-strait tensions.

The Taiwan-funded classes are part of a partnership with the U.S. government that includes $1.8 million from Taiwan for U.S. State Department-managed language training programs and $1 million from the U.S. for Fulbright student and teacher exchanges.

They are a counterweight to China’s controversial Confucius Institute, which has been scaled back by U.S. officials amid concerns that it threatened academic freedom and gave the Chinese government too much access to the American educational system.

“It’s highly possible that if the Taiwanese state is looked upon favorably, then people are going to be sort of thinking about these programs with better opinions than they’re going to be thinking about the Confucius Institute programs,” said Jennifer Hubbert, a professor of anthropology and Asian studies at Lewis and Clark College.

The Taiwanese government in the last few years opened, as of March, 54 Centers for Mandarin Learning in the U.S., including 17 in California. It aims to have as many as 100 centers around the world by 2025.

In Europe, the Taiwanese Mandarin classes are taught in nine countries, including France, Germany, Sweden and the U.K.

In a promotional video, Chen-yuan Tung, who was minister of Taiwan’s Overseas Community Affairs Council, emphasized the “long cultural traditions” behind the writing system used in Taiwan. He also highlighted the freedom to discuss any topic in the classroom, drawing a sharp contrast with authoritarian China, where dissenting voices on the internet are often shut down and people are thrown in jail for criticizing the government.

“We preserve tradition and culture very well, and our democratic system guarantees freedom of speech,” Tung said.

Each school sets its own policies and fees, and teachers prepare their own materials, said Louis M. Huang, former director general of the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Los Angeles, the equivalent of a consulate, which China won’t allow Taiwan to have.

In San Marino, conversational Mandarin is offered for adults at the beginning and intermediate levels for $220 a semester.

Some of the differences between Mandarin spoken and written in Taiwan compared to mainland China.

The Taiwan-sponsored classes represent a sliver of the Mandarin instruction in the U.S., which ranges from private tutoring to Saturday schools for Chinese American children to rigorous high school and college courses.

After China’s economy opened to foreign investment in 1978, and Americans began seeing the country as a business opportunity, Mandarin grew in popularity, despite how hard it is for English speakers to learn. China’s Confucius Institute capitalized on that interest, reaching deep into American schools.

For instance, in the Northern California town of Redding, one of the only chances for high school students to learn Mandarin — and travel to China on an exchange program — came through a Confucius Institute collaboration with San Francisco State University.

San Francisco State University has shut down its Confucius Institute, a China-funded language and culture program, under pressure from federal officials suspicious of ulterior motives to infiltrate American campuses.

Amid growing mistrust between the two superpowers, the U.S. Department of Defense said in 2019 that it would not provide funding for universities with Confucius Institutes, forcing many, including San Francisco State, to close the institutes and scale down their Mandarin programs. Only one Confucius Institute — through the San Diego Global Education Initiative — remains in California, according to the National Assn. of Scholars, a conservative education advocacy group long critical of the institutes. The group also lists Stanford, but the university in an email said it no longer runs the institute.

The Chinese Consulate in Los Angeles did not respond to a request for comment.

But Taiwan’s ability to influence Mandarin education is limited by its small size compared with China, said Jamie Horsley, a senior fellow at Paul Tsai China Center at Yale Law School.

“How many teachers from Taiwan can we actually bring over here? It’s just a handful,” she said. “It helps, and I think that was a great idea to tap more into Taiwan and that resource, and [it] also allows people to learn more about what’s happening in Taiwan.”

Even without the Confucius Institutes, many universities offer comprehensive Mandarin curricula. Last fall, UCLA offered two elementary Chinese classes, each with the capacity for 100 students, who can continue through advanced Chinese for international business and readings in Chinese literature.

In Taiwan after World War II, the nationalist government imposed Mandarin as the official language on a population that spoke mostly the Minnan or Hakka variants of Chinese.

With contact cut off between Taiwan and the mainland for decades during the Cold War, Mandarin evolved independently in each place. Today, the languages are roughly analogous to British versus American English, with minor differences in vocabulary and accent.

For example, in the standard Mandarin spoken in China, baba — father — is pronounced with an emphasis on the first syllable, said Hongyin Tao, a professor of Chinese language and linguistics at UCLA. In Taiwanese Mandarin, the second ba sounds stronger.

“It’s something people joke about,” Tao said.

With a more slurred diction and less emphasis on enunciating each syllable, Taiwan Mandarin sounds “quite sweet and soft,” said Cecilia Chen, a Mandarin instructor in Taiwan who produced a video showing the differences.

In one example of a vocabulary difference, trash is laji in the mainland and lese in Taiwan.

In China in the 1950s and 1960s, Mao Zedong tried to make the writing system, which dates back thousands of years, more accessible by simplifying the characters. They still have to be learned one by one, but there are fewer strokes to memorize.

For Taiwanese like Huang, the former director general in Los Angeles, traditional characters are a point of pride, showing that Taiwan has preserved aspects of Chinese culture lost on the mainland.

A truism in Taiwan is that the simplified character for love is stripped of its heart, since the only difference is the absence of the “heart” component. And how can love lack heart?

“If you learn the traditional characters ... from the character itself, you understand the meaning,” Huang said. “If you learn simplified ... those characters don’t carry the real meanings.”

At the San Marino class, Chuang wrote dian nao on the board. Dian is electricity, and nao is brain — put together, they mean “computer.”

In traditional Chinese, dian has 13 strokes, compared with five in simplified. The simplified version lacks a component that means “rain,” which is also used in “thunder” and other words.

Larry Lovan worked in Fuzhou, China, as a design intern in 2015 but didn’t pick up much of the language. Now, he makes a round trip of more than three hours from his home in Hemet to attend the class every Saturday.

A 32-year-old business consultant specializing in web design, Lovan hopes that learning traditional characters will help him communicate with clients in both China and Taiwan, since it’s generally easier to learn the traditional forms first, then simplified, rather than the other way around.

He likes the small class size and the lack of grades, which lets him study at his own pace.

“It’s however much you want to learn and whatever you can take and absorb,” he said. “But there’s no judgment.”

The center in San Marino also offers a weekly class for government officials, teaching basic, practical Mandarin.

Mario Rueda, San Marino’s fire chief and acting city manager, took the class last year, prompted by the previous city manager, who encouraged colleagues to learn some basics in a community where nearly half the population is Chinese or Taiwanese. Rueda didn’t pick up much Mandarin beyond basic greetings. Still, some lessons have stayed with him, like how to properly present a business card: with two hands, as a sign of respect.

“There was much more than just the learning of a language,” he said.

City officials are aware of the tensions across the Taiwan Straits, which have ramped up since then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan last summer, prompting China to fire missiles over the island.

But Rueda said he didn’t give much thought to who was sponsoring the class.

“We see the friction on the news, and I know it’s a concern,” he said. “But it really isn’t front and center in San Marino.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.